36 9.3 Organizing

[Author removed at request of original publisher]

Learning Objectives

- Explain the process of organizing a speech.

- Identify common organizational patterns.

- Incorporate supporting materials into a speech.

- Employ verbal citations for various types of supporting material.

- List key organizing signposts.

- Identify the objectives of a speech introduction.

- Identify the objectives of a speech conclusion.

When organizing your speech, you want to start with the body. Even though most students want to start with the introduction, I explain that it’s difficult to introduce and preview something that you haven’t yet developed. A well-structured speech includes an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Think of this structure as a human body. This type of comparison dates back to Plato, who noted, “every speech ought to be put together like a living creature” (Winans, 1917). The introduction is the head, the body is the torso and legs, and the conclusion is the feet. The information you add to this structure from your research and personal experience is the organs and muscle. The transitions you add are the connecting tissues that hold the parts together, and a well-practiced delivery is the skin and clothing that makes everything presentable.

Organizing the Body of Your Speech

Writing the body of your speech takes the most time in the speech-writing process. Your specific purpose and thesis statements should guide the initial development of the body, which will then be more informed by your research process. You will determine main points that help achieve your purpose and match your thesis. You will then fill information into your main points by incorporating the various types of supporting material discussed previously. Before you move on to your introduction and conclusion, you will connect the main points together with transitions and other signposts.

Determining Your Main Points

Think of each main point as a miniature speech within your larger speech. Each main point will have a central idea, meet some part of your specific purpose, and include supporting material from your research that relates to your thesis. Reviewing the draft of your thesis and specific purpose statements can lead you to research materials. As you review your research, take notes on and/or highlight key ideas that stick out to you as useful, effective, relevant, and interesting. It is likely that these key ideas will become the central ideas of your main points, or at least subpoints. Once you’ve researched your speech enough to achieve your specific purpose, support your thesis, and meet the research guidelines set forth by your instructor, boss, or project guidelines, you can distill the research down to a series of central ideas. As you draft these central ideas, use parallel wording, which is similar wording among key organizing signposts and main points that helps structure a speech. Using parallel wording in your central idea statement for each main point will also help you write parallel key signposts like the preview statement in the introduction, transitions between main points, and the review statement in the conclusion. The following example shows parallel wording in the central ideas of each main point in a speech about the green movement and schools:

- The green movement in schools positively affects school buildings and facilities.

- The green movement in schools positively affects students.

- The green movement in schools positively affects teachers.

While writing each central idea using parallel wording is useful for organizing information at this stage in the speech-making process, you should feel free to vary the wording a little more in your actual speech delivery. You will still want some parallel key words that are woven throughout the speech, but sticking too close to parallel wording can make your content sound forced or artificial.

After distilling your research materials down, you may have several central idea statements. You will likely have two to five main points, depending on what your instructor prefers, time constraints, or the organizational pattern you choose. All the central ideas may not get converted into main points; some may end up becoming subpoints and some may be discarded. Once you get your series of central ideas drafted, you will then want to consider how you might organize them, which will help you narrow your list down to what may actually end up becoming the body of your speech.

Organizing Your Main Points

There are several ways you can organize your main points, and some patterns correspond well to a particular subject area or speech type. Determining which pattern you will use helps filter through your list of central ideas generated from your research and allows you to move on to the next step of inserting supporting material into your speech. Here are some common organizational patterns.

Topical Pattern

When you use the topical pattern, you are breaking a large idea or category into smaller ideas or subcategories. In short you are finding logical divisions to a whole. While you may break something down into smaller topics that will make two, three, or more main points, people tend to like groups of three. In a speech about the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, for example, you could break the main points down to (1) the musicians who performed, (2) the musicians who declined to perform, and (3) the audience. You could also break it down into three specific performances—(1) Santana, (2) The Grateful Dead, and (3) Creedence Clearwater Revival—or three genres of music—(1) folk, (2) funk, and (3) rock.

The topical pattern breaks a topic down into logical divisions but doesn’t necessarily offer any guidance in ordering them. To help determine the order of topical main points, you may consider the primacy or recency effect. You prime an engine before you attempt to start it and prime a surface before you paint it. The primacy effect is similar in that you present your best information first in order to make a positive impression and engage your audience early in your speech. The recency effect is based on the idea that an audience will best remember the information they heard most recently. Therefore you would include your best information last in your speech to leave a strong final impression. Both primacy and recency can be effective. Consider your topic and your audience to help determine which would work best for your speech.

Chronological Pattern

A chronological pattern helps structure your speech based on time or sequence. If you order a speech based on time, you may trace the development of an idea, product, or event. A speech on Woodstock could cover the following: (1) preparing for the event, (2) what happened during the event, and (3) the aftermath of the event. Ordering a speech based on sequence is also chronological and can be useful when providing directions on how to do something or how a process works. This could work well for a speech on baking bread at home, refinishing furniture, or harvesting corn. The chronological pattern is often a good choice for speeches related to history or demonstration speeches.

Spatial Pattern

The spatial pattern arranges main points based on their layout or proximity to each other. A speech on Woodstock could focus on the layout of the venue, including (1) the camping area, (2) the stage area, and (3) the musician/crew area. A speech could also focus on the components of a typical theater stage or the layout of the new 9/11 memorial at the World Trade Center site.

Problem-Solution Pattern

The problem-solution pattern entails presenting a problem and offering a solution. This pattern can be useful for persuasive speaking—specifically, persuasive speeches focused on a current societal issue. This can also be coupled with a call to action asking an audience to take specific steps to implement a solution offered. This organizational pattern can be applied to a wide range of topics and can be easily organized into two or three main points. You can offer evidence to support your claim that a problem exists in one main point and then offer a specific solution in the second main point. To be more comprehensive, you could set up the problem, review multiple solutions that have been proposed, and then add a third main point that argues for a specific solution out of the ones reviewed in the second main point. Using this pattern, you could offer solutions to the problem of rising textbook costs or offer your audience guidance on how to solve conflicts with roommates or coworkers.

Cause-Effect Pattern

The cause-effect pattern sets up a relationship between ideas that shows a progression from origin to result. You could also start with the current situation and trace back to the root causes. This pattern can be used for informative or persuasive speeches. When used for informing, the speaker is explaining an established relationship and citing evidence to support the claim—for example, accessing unsecured, untrusted websites or e-mails leads to computer viruses. When used for persuading, the speaker is arguing for a link that is not as well established and/or is controversial—for example, violent video games lead to violent thoughts and actions. In a persuasive speech, a cause-effect argument is often paired with a proposed solution or call to action, such as advocating for stricter age restrictions on who can play violent video games. When organizing an informative speech using the cause-effect pattern, be careful not to advocate for a particular course of action.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is a five-step organization pattern that attempts to persuade an audience by making a topic relevant, using positive and/or negative motivation, and including a call to action. The five steps are (1) attention, (2) need, (3) satisfaction, (4) visualization, and (5) action (Monroe & Ehninger, 1964).

The attention step is accomplished in the introduction to your speech. Whether your entire speech is organized using this pattern or not, any good speaker begins by getting the attention of the audience. We will discuss several strategies in Section 9 “Getting Your Audience’s Attention” for getting an audience’s attention. The next two steps set up a problem and solution.

After getting the audience’s attention you will want to establish that there is a need for your topic to be addressed. You will want to cite credible research that points out the seriousness or prevalence of an issue. In the attention and need steps, it is helpful to use supporting material that is relevant and proxemic to the audience.

Once you have set up the need for the problem to be addressed, you move on to the satisfaction step, where you present a solution to the problem. You may propose your own solution if it is informed by your research and reasonable. You may also propose a solution that you found in your research.

The visualization step is next and incorporates positive and/or negative motivation as a way to support the relationship you have set up between the need and your proposal to satisfy the need. You may ask your audience to visualize a world where things are better because they took your advice and addressed this problem. This capitalizes on positive motivation. You may also ask your audience to visualize a world where things are worse because they did not address the issue, which is a use of negative motivation. Now that you have hopefully persuaded your audience to believe the problem is worthy of addressing, proposed a solution, and asked them to visualize potential positive or negative consequences, you move to the action step.

The action step includes a call to action where you as basically saying, “Now that you see the seriousness of this problem, here’s what you can do about it.” The call to action should include concrete and specific steps an audience can take. Your goal should be to facilitate the call to action, making it easy for the audience to complete. Instead of asking them to contact their elected officials, you could start an online petition and make the link available to everyone. You could also bring the contact information for officials that represent that region so the audience doesn’t have to look them up on their own. Although this organizing pattern is more complicated than the others, it offers a proven structure that can help you organize your supporting materials and achieve your speech goals.

Incorporating Supporting Material

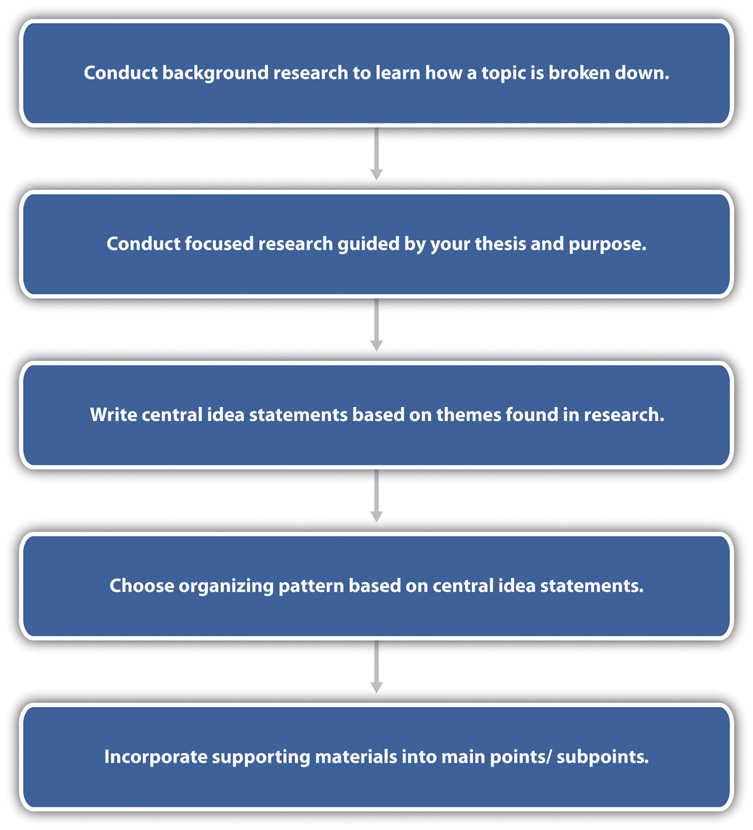

So far, you have learned several key steps in the speech creation process, which are reviewed in Figure 9.4 “From Research to Main Points”. Now you will begin to incorporate more specific information from your supporting materials into the body of your speech. You can place the central ideas that fit your organizational pattern at the beginning of each main point and then plug supporting material in as subpoints.

This information will also make up the content of your formal and speaking outlines, which we will discuss more in Section 9.4 “Outlining”. Remember that you want to include a variety of supporting material (examples, analogies, statistics, explanations, etc.) within your speech. The information that you include as subpoints helps back up the central idea that started the main point. Depending on the length of your speech and the depth of your research, you may also have sub-subpoints that back up the claim you are making in the subpoint. Each piece of supporting material you include eventually links back to the specific purpose and thesis statement. This approach to supporting your speech is systematic and organized and helps ensure that your content fits together logically and that your main points are clearly supported and balanced.

One of the key elements of academic and professional public speaking is verbally citing your supporting materials so your audience can evaluate your credibility and the credibility of your sources. You should include citation information in three places: verbally in your speech, on any paper or electronic information (outline, PowerPoint), and on a separate reference sheet. Since much of the supporting material you incorporate into your speech comes directly from your research, it’s important that you include relevant citation information as you plug this information into your main points. Don’t wait to include citation information once you’ve drafted the body of your speech. At that point it may be difficult to retrace your steps to locate the source of a specific sentence or statistic. As you paraphrase or quote your supporting material, work the citation information into the sentences; do not clump the information together at the end of a sentence, or try to cite more than one source at the end of a paragraph or main point. It’s important that the audience hear the citations as you use the respective information so it’s clear which supporting material matches up with which source.

Writing key bibliographic information into your speech will help ensure that you remember to verbally cite your sources and that your citations will be more natural and flowing and less likely to result in fluency hiccups. At minimum, you should include the author, date, and source in a verbal citation. Sometimes more information is necessary. When citing a magazine, newspaper, or journal article, it is more important to include the source name than the title of the article, since the source name—for example, Newsweek—is what the audience needs to evaluate the speaker’s credibility. For a book, make sure to cite the title and indicate that the source is a book. When verbally citing information retrieved from a website, you do not want to try to recite a long and cumbersome URL in your speech. Most people don’t even make it past the “www.” before they mess up. It is more relevant to audiences for speakers to report the sponsor/author of the site and the title of the web page, or section of the website, where they obtained their information. When getting information from a website, it is best to use “official” organization websites or government websites. When you get information from an official site, make sure you state that in your citation to add to your credibility. For an interview, state the interviewee’s name, their credentials, and when the interview took place. Advice for verbally citing sources and examples from specific types of sources follow:

-

Magazine article

- “According to an article by Niall Ferguson in the January 23, 2012, issue of Newsweek, we can expect much discussion about ‘class warfare’ in the upcoming presidential and national election cycle. Ferguson reports that…”

- “As reported by Niall Ferguson, in the January 23, 2012, issue of Newsweek, many candidates denounce talking points about economic inequality…”

-

Newspaper article

- “On November 26, 2011, Eithne Farry of The Daily Telegraph of London reported that…”

- “An article about the renewed popularity of selling products in people’s own homes appeared in The Daily Telegraph on November 26, 2011. Eithne Farry explored a few of these ‘blast-from-the-past’ styled parties…”

-

Website

- “According to information I found at ready.gov, the website of the US Department of Homeland Security, US businesses and citizens…”

- “According to information posted on the US Department of Homeland Security’s official website,…”

- “Helpful information about business continuity planning can be found on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s official website, located at ready.gov…”

-

Journal article

- “An article written by Dr. Nakamura and Dr. Kikuchi, at Meiji University in Tokyo, found that the Fukushima disaster was complicated by Japan’s high nuclear consciousness. Their 2011 article published in the journal Public Administration Today reported that…”

- “In a 2012 article published in Public Administration Review, Professors Nakamura and Kikuchi reported that the Fukushima disaster was embarrassing for a country with a long nuclear history…”

- “Nakamura and Kikuchi, scholars in crisis management and public policy, authored a 2011 article about the failed crisis preparation at the now infamous Fukushima nuclear plant. Their Public Administration Review article reports that…”

- Bad example (doesn’t say where the information came from). “A 2011 study by Meiji University scholars found the crisis preparations at a Japanese nuclear plant to be inadequate…”

-

Book

- “In their 2008 book At War with Metaphor, Steuter and Wills describe how we use metaphor to justify military conflict. They report…”

- “Erin Steuter and Deborah Wills, experts in sociology and media studies, describe the connections between metaphor and warfare in their 2008 book At War with Metaphor. They both contend that…”

- “In their 2008 book At War with Metaphor, Steuter and Wills reveal…”

-

Interview

- “On February 20 I conducted a personal interview with Dr. Linda Scholz, a communication studies professor at Eastern Illinois University, to learn more about Latina/o Heritage Month. Dr. Scholz told me that…”

- “I conducted an interview with Dr. Linda Scholz, a communication studies professor here at Eastern, and learned that there are more than a dozen events planned for Latina/o Heritage Month.”

- “In a telephone interview I conducted with Dr. Linda Scholz, a communication studies professor, I learned…”

“Getting Critical”

Plagiarism

During the process of locating and incorporating supporting material into your speech, it’s important to practice good research skills to avoid intentional or unintentional plagiarism. Plagiarism, as we have already learned, is the uncredited use of someone else’s words or ideas. It’s important to note that most colleges and universities have strict and detailed policies related to academic honesty. You should be familiar with your school’s policy and your instructor’s policy. At many schools, there are consequences for academic dishonesty whether it is intentional or unintentional. Although many schools try to make a learning opportunity out of an initial violation, multiple violations could lead to suspension or expulsion. At the class level, plagiarism may result in an automatic “F” for the assignment or the course.

Over my years of teaching, I have encountered more than a dozen cases of plagiarism. While that is not a large percentage in relation to the large number of students I have taught, I have noticed that the instances have steadily increased over the past few years. I don’t think this is because students are becoming more dishonest; I think it’s become easier to locate and copy information and easier to catch those who do. I always remind my students that they do not have access to a secret version of the Internet that faculty can’t access. If it takes a student five seconds to find a speech to plagiarize online, it will take me the same amount of time. Software programs like Turnitin.com also aid instructors in detecting plagiarism.

Being organized and thorough in your research can help avoid a situation where you feel backed into a corner and fake some sources or leave out some citations because you’re out of time. One key to avoiding this type of situation is to keep good records as you research and write. First, as you locate sources, always record all the key bibliographic information. I know from experience how frustrating it can be to try to locate a source after you’ve already worked it into your speech or paper, and you have the quote or paraphrase but can’t retrace your steps to find where you took it from. Printing the source, downloading the PDF, or copying and pasting the URL as soon as you locate the source can help you retrace your steps if needed.

Save drafts of your writing as you progress. Each day I work on a chapter for this book, I go to the “File” menu, choose “Save As,” and amend the file name to include that day’s date. That way I have a record that shows my work. The various style guides for writing also offer specific advice on how to cite sources and how to conduct research. You are probably familiar with MLA (Modern Language Association), used mostly in English and the humanities, and APA (American Psychological Association), which is used mostly in the social sciences. There’s also the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), used in history and also the style this book is in, and CBE (developed by the Council of Science Editors), which is used in biological and earth sciences. Since each manual is geared toward a different academic area, it’s a good source for specific research-related questions. When in doubt about how to conduct or cite research, you can also ask your instructor for guidance.

- Why do you think instances of academic dishonesty have been steadily increasing over the past few years?

- What is your school’s policy in academic honesty? What is your instructor’s policy? What are the potential consequences for violating this policy at the school and classroom levels?

- Based on what you learned here, what are some strategies you can employ to make your research process more organized?

Signposts

Signposts on highways help drivers and passengers navigate places they are not familiar with and give us reminders and warnings about what to expect down the road. Signposts in speeches are statements that help audience members navigate the turns of your speech. There are several key signposts in your speech. In the order you will likely use them, they are preview statement, transition between introduction and body, transitions between main points, transition from body to conclusion, and review statement (see Table 9.3 “Organizing Signposts” for a review of the key signposts with examples). While the preview and review statements are in the introduction and conclusion, respectively, the other signposts are all transitions that help move between sections of your speech.

Table 9.3 Organizing Signposts

| Signpost | Example |

|---|---|

| Preview statement | “Today, I’d like to inform you about the history of Habitat for Humanity, the work they have done in our area, and my experiences as a volunteer.” |

| Transition from introduction to body | “Let’s begin with the history of Habitat for Humanity.” |

| Transition from main point one to main point two | “Now that you know more about the history of Habitat for Humanity, let’s look at the work they have done in our area.” |

| Transition from main point two to main point three | “Habitat for Humanity has done a lot of good work in our area, and I was fortunate to be able to experience this as a volunteer.” |

| Transition from body to conclusion | “In closing, I hope you now have a better idea of the impact this well-known group has had.” |

| Review statement | “Habitat for Humanity is an organization with an inspiring history that has done much for our area while also providing an opportunity for volunteers, like myself, to learn and grow.” |

There are also signposts that can be useful within sections of your speech. Words and phrases like Aside from and While are good ways to transition between thoughts within a main point or subpoint. Organizing signposts like First, Second, and Third can be used within a main point to help speaker and audience move through information. The preview in the introduction and review in the conclusion need not be the only such signposts in your speech. You can also include internal previews and internal reviews in your main points to help make the content more digestible or memorable.

In terms of writing, compose transitions that are easy for you to remember and speak. Pioneer speech teacher James A. Winans wrote in 1917 that “it is at a transition, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, that the speaker who staggers or breaks down, meets his [or her] difficulty” (Winans, 1917). His observation still holds true today. Key signposts like the ones in Table 9.3 “Organizing Signposts” should be concise, parallel, and obviously worded. Going back to the connection between speech signposts and signposts that guide our driving, we can see many connections. Speech signposts should be one concise sentence. Stop signs, for example, just say, “STOP.” They do not say, “Your vehicle is now approaching an intersection. Please bring it to a stop.”

Signposts in your speech guide the way for your audience members like signposts on the highway guide drivers.

Doug Kerr – Minnesota State Highway 5 – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Try to remove unnecessary words from key signposts to make them more effective and easier to remember and deliver. Speech signposts should also be parallel. All stop signs are octagonal with a red background and white lettering, which makes them easily recognizable to drivers. If the wording in your preview statement matches with key wording in your main points, transitions between main points, and review statement, then your audience will be better able to follow your speech. Last, traffic signposts are obvious. They are bright colors, sometimes reflective, and may even have flashing lights on them. A “Road Closed” sign painted in camouflage isn’t a good idea and could lead to disaster.

Being too vague or getting too creative with your speech signposts can also make them disappear into the background of your speech. My students have expressed concern that using parallel and obvious wording in speech signposts would make their speech boring or insult the intelligence of their audience. This is not the case. As we learned in Chapter 5 “Listening”, most people struggle to be active listeners, so making a speech more listenable is usually appreciated. In addition, these are just six sentences in a much larger speech, so they are spaced out enough to not sound repetitive, and they can serve as anchor points to secure the attention of the audience.

In addition to well-written signposts, you want to have well-delivered signposts. Nonverbal signposts include pauses and changes in rate, pitch, or volume that help emphasize transitions within a speech. I have missed students’ signposts before, even though they were well written, because they did not stand out in the delivery. Here are some ways you can use nonverbal signposting: pause before and after your preview and review statements so they stand out, pause before and after your transitions between main points so they stand out, and slow your rate and lower your pitch on the closing line of your speech to provide closure.

Introduction

We all know that first impressions matter. Research shows that students’ impressions of instructors on the first day of class persist throughout the semester (Laws et al., 2010). First impressions are quickly formed, sometimes spontaneous, and involve little to no cognitive effort. Despite the fact that first impressions aren’t formed with much conscious effort, they form the basis of inferences and judgments about a person’s personality (Lass-Hennemann, et al., 2011). For example, the student who approaches the front of the class before their speech wearing sweatpants and a t-shirt, looks around blankly, and lets out a sigh before starting hasn’t made a very good first impression. Even if the student is prepared for the speech and delivers it well, the audience has likely already associated what they observed with personality traits of the student (i.e., lazy, indifferent), and those associations now have staying power in the face of contrary evidence that comes later.

Because of the power of first impressions, a speaker who seems unprepared in his or her introduction will likely be negatively evaluated even if the speech improves.

Nadine Dereza – ’Insider Secrets of Public Speaking’. – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Your introduction is only a fraction of your speech, but in that first minute or so, your audience decides whether or not they are interested in listening to the rest of the speech. There are four objectives that you should accomplish in your introduction. They include getting your audience’s attention, introducing your topic, establishing credibility and relevance, and previewing your main points.

Getting Your Audience’s Attention

There are several strategies you can use to get your audience’s attention. Although each can be effective on its own, combining these strategies is also an option. A speaker can get their audience’s attention negatively, so think carefully about your choice. The student who began his speech on Habitat for Humanity by banging on the table with a hammer definitely got his audience’s attention during his 8:00 a.m. class, but he also lost credibility in that moment because many in the audience probably saw him as a joker rather than a serious speaker. The student who started her persuasive speech against animal testing with a little tap dance number ended up stumbling through the first half of her speech when she was thrown off by the confused looks the audience gave her when she finished her “attention getter.” These cautionary tales point out the importance of choosing an attention getter that is appropriate, meaning that it’s unusual enough to get people interested—but not over the top—and relevant to your speech topic.

Use Humor

In one of my favorite episodes of the television show The Office, titled “Dwight’s Speech,” the boss, Michael Scott, takes the stage at a regional sales meeting for a very nervous Dwight, who has been called up to accept an award. In typical Michael Scott style, he attempts to win the crowd over with humor and fails miserably. I begin this section on using humor to start a speech with this example because I think erring on the side of caution when it comes to humor tends to be the best option, especially for new speakers. I have had students who think that cracking a joke will help lighten the mood and reduce their anxiety. If well executed, this is a likely result and can boost the confidence of the speaker and get the audience hooked. But even successful comedians still bomb, and many recount stories of excruciating instances in which they failed to connect with an audience. So the danger lies in the poorly executed joke, which has the reverse effect, heightening the speaker’s anxiety and leading the audience to question the speaker’s competence and credibility. In general, when a speech is supposed to be professional or formal, as many in-class speeches are, humor is more likely to be seen as incongruous with the occasion. But there are other situations where a humorous opening might fit perfectly. For example, a farewell speech to a longtime colleague could start with an inside joke. When considering humor, it’s good to get feedback on your idea from a trusted source.

Cite a Startling Fact or Statistic

As you research your topic, take note of any information that defies your expectations or surprises you. If you have a strong reaction to something you learn, your audience may, too. When using a startling fact or statistic as an attention getter, it’s important to get the most bang for your buck. You can do this by sharing more than one fact or statistic that builds up the audience’s interest. When using numbers, it’s also good to repeat and/or repackage the statistics so they stick in the audience’s mind, which you can see in the following example:

In 1994, sixteen states reported that 15–19 percent of their population was considered obese. Every other state reported obesity rates less than that. In 2010, no states reported obesity rates in that same category of 15–19 percent, because every single state had at least a 20 percent obesity rate. In just six years, we went from no states with an obesity rate higher than 19 percent, to fifty. Currently, the national obesity rate for adults is nearly 34 percent. This dramatic rise in obesity is charted on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website, and these rates are expected to continue to rise.

The speaker could have just started by stating that nearly 34 percent of the US adult population was obese in 2011. But statistics aren’t meaningful without context. So sharing how that number rose dramatically over six years helps the audience members see the trend and understand what the current number means. The fourth sentence repackages and summarizes the statistics mentioned in the first three sentences, which again sets up an interesting and informative contrast. Last, the speaker provides a verbal citation for the source of the statistic.

Use a Quotation

Some quotations are attention getting and some are boring. Some quotations are relevant and moving and some are abstract and stale. If you choose to open your speech with a quotation, choose one that is attention getting, relevant, and moving. The following example illustrates some tips for using a quote to start a speech: “‘The most important question in the world is ‘Why is the child crying?’’ This quote from author Alice Walker is at the heart of my speech today. Too often, people see children suffering at the hands of bullies and do nothing about it until it’s too late. That’s why I believe that all public schools should adopt a zero-tolerance policy on bullying.”

Notice that the quote is delivered first in the speech, then the source of the quote is cited. Since the quote, like a starting fact or statistic just discussed, is the attention-getting part, it’s better to start with that than the citation. Next, the speaker explains why the quote is relevant to the speech. Just because a quote seems relevant to you doesn’t mean the audience will also pick up on that relevance, so it’s best to make that explicit right after you use and cite the quote. Also evaluate the credibility of the source on which you found the quote. Many websites that make quotations available care more about selling pop-up ads than the accuracy of their information. Students who don’t double-check the accuracy of the quote may end up attributing the quote to the wrong person or citing a made-up quote.

Ask a Question

Starting a speech with a question is a common attention getter, but in reality many of the questions that I have heard start a speech are not very attention getting. It’s important to note that just because you use one of these strategies, that doesn’t make it automatically appealing to an audience. A question can be mundane and boring just like a statistic, quotation, or story can.

A rhetorical question is different from a direct question. When a speaker asks a direct question, they actually want a response from their audience. A rhetorical question is designed to elicit a mental response from the audience, not a verbal or nonverbal one. In short, a rhetorical question makes an audience think. Asking a direct question of your audience is warranted only if the speaker plans on doing something with the information they get from the audience. I can’t recall a time in which a student asked a direct question to start their speech and did anything with that information. Let’s say a student starts the speech with the direct question “By a show of hands, how many people have taken public transportation in the past week?” and sixteen out of twenty students raise their hands. If the speaker is arguing that more students should use public transportation and she expected fewer students to raise their hands, is she going to change her speech angle on the spot? Since most speakers move on from their direct question without addressing the response they got from the audience, they have not made their attention getter relevant to their topic. So, if you use a direct question, make sure you have a point to it and some way to incorporate the responses into the speech.

A safer bet is to ask a rhetorical question that elicits only a mental response. A good rhetorical question can get the audience primed to think about the content of the speech. When asked as a series of questions and combined with startling statistics or facts, this strategy can create suspense and hook an audience. The following is a series of rhetorical questions used in a speech against the testing of cosmetics on animals: “Was the toxicity of the shampoo you used this morning tested on the eyes of rabbits? Would you let someone put a cosmetic in your dog’s eye to test its toxicity level? Have you ever thought about how many products that you use every day are tested on animals?” Make sure you pause after your rhetorical question to give the audience time to think. Don’t pause for too long, though, or an audience member may get restless and think that you’re waiting for an actual response and blurt out what he or she was thinking.

Tell a Story

When you tell a story, whether in the introduction to your speech or not, you should aim to paint word pictures in the minds of your audience members. You might tell a story from your own life or recount a story you found in your research. You may also use a hypothetical story, which has the advantage of allowing you to use your creativity and help place your audience in unusual situations that neither you nor they have actually experienced. When using a hypothetical story, you should let your audience know it’s not real, and you should present a story that the audience can relate to. Speakers often let the audience know a story is not real by starting with the word imagine. As I noted, a hypothetical example can allow you to speak beyond the experience of you and your audience members by having them imagine themselves in unusual circumstances. These circumstances should not be so unusual that the audience can’t relate to them. I once had a student start her speech by saying, “Imagine being held as a prisoner of war for seven years.” While that’s definitely a dramatic opener, I don’t think students in our class were able to really get themselves into that imagined space in the second or two that we had before the speaker moved on. It may have been better for the speaker to say, “Think of someone you really care about. Visualize that person in your mind. Now, imagine that days and weeks go by and you haven’t heard from that person. Weeks turn into months and years, and you have no idea if they are alive or dead.” The speaker could go on to compare that scenario to the experiences of friends and family of prisoners of war. While we may not be able to imagine being held captive for years, we all know what it’s like to experience uncertainty regarding the safety of a loved one.

Introducing the Topic

Introducing the topic of your speech is the most obvious objective of an introduction, but speakers sometimes forget to do this or do not do it clearly. As the author of your speech, you may think that what you’re talking about is obvious. Sometimes a speech topic doesn’t become obvious until the middle of a speech. By that time, however, it’s easy to lose an audience that didn’t get clearly told the topic of the speech in the introduction. Introducing the topic is done before the preview of main points and serves as an introduction to the overall topic. The following are two ways a speaker could introduce the topic of childhood obesity: “Childhood obesity is a serious problem facing our country,” or “Today I’ll persuade you that childhood obesity is a problem that can no longer be ignored.”

Establishing Credibility and Relevance

The way you write and deliver your introduction makes an important first impression on your audience. But you can also take a moment in your introduction to explicitly set up your credibility in relation to your speech topic. If you have training, expertise, or credentials (e.g., a degree, certificate, etc.) relevant to your topic, you can share that with your audience. It may also be appropriate to mention firsthand experience, previous classes you have taken, or even a personal interest related to your topic. For example, I had a student deliver a speech persuading the audience that the penalties for texting and driving should be stricter. In his introduction, he mentioned that his brother’s girlfriend was killed when she was hit by a car driven by someone who was texting. His personal story shared in the introduction added credibility to the overall speech.

I ask my students to imagine that when they finish their speech, everyone in the audience will raise their hands and ask the question “Why should I care about what you just said?”

Imagine that your audience members will all ask, “Why should I care about your topic?” and work to proactively address relevance throughout your speech.

U.S. Department of Agriculture – CC BY 2.0.

This would no doubt be a nerve-racking experience. However, you can address this concern by preemptively answering this question in your speech. A good speaker will strive to make his or her content relevant to the audience throughout the speech, and starting this in the introduction appeals to an audience because the speaker is already answering the “so what?” question. When you establish relevance, you want to use immediate words like I, you, we, our, or your. You also want to address the audience sitting directly in front of you. While many students are good at making a topic relevant to humanity in general, it takes more effort to make the content relevant to a specific audience.

Previewing Your Main Points

The preview of main points is usually the last sentence of your introduction and serves as a map of what’s to come in the speech. The preview narrows your introduction of the topic down to the main ideas you will focus on in the speech. Your preview should be one sentence, should include wording that is parallel to the key wording of your main points in the body of your speech, and should preview your main points in the same order you discuss them in your speech. Make sure your wording is concise so your audience doesn’t think there will be four points when there are only three. The following example previews the main points for a speech on childhood obesity: “Today I’ll convey the seriousness of the obesity epidemic among children by reviewing some of the causes of obesity, common health problems associated with it, and steps we can take to help ensure our children maintain a healthy weight.”

Conclusion

How you conclude a speech leaves an impression on your audience. There are three important objectives to accomplish in your conclusion. They include summarizing the importance of your topic, reviewing your main points, and closing your speech.

Summarizing the Importance of Your Topic

After you transition from the body of your speech to the conclusion, you will summarize the importance of your topic. This is the “take-away” message, or another place where you can answer the “so what?” question. This can often be a rewording of your thesis statement. The speech about childhood obesity could be summarized by saying, “Whether you have children or not, childhood obesity is a national problem that needs to be addressed.”

Reviewing Your Main Points

Once you have summarized the overall importance of your speech, you review the main points. The review statement in the conclusion is very similar to the preview statement in your introduction. You don’t have to use the exact same wording, but you still want to have recognizable parallelism that connects the key idea of each main point to the preview, review, and transitions. The review statement for the childhood obesity speech could be “In an effort to convince you of this, I cited statistics showing the rise of obesity, explained common health problems associated with obesity, and proposed steps that parents should take to ensure their children maintain a healthy weight.”

Closing Your Speech

Like the attention getter, your closing statement is an opportunity for you to exercise your creativity as a speaker. Many students have difficulty wrapping up the speech with a sense of closure and completeness. In terms of closure, a well-written and well-delivered closing line signals to your audience that your speech is over, which cues their applause. You should not have to put an artificial end to your speech by saying “thank you” or “that’s it” or “that’s all I have.” In terms of completeness, the closing line should relate to the overall speech and should provide some “take-away” message that may leave an audience thinking or propel them to action. A sample closing line could be “For your health, for our children’s health, and for our country’s health, we must take steps to address childhood obesity today.” You can also create what I call the “ribbon and bow” for your speech by referring back to the introduction in the closing of your speech. For example, you may finish an illustration or answer a rhetorical question you started in the introduction.

Although the conclusion is likely the shortest part of the speech, I suggest that students practice it often. Even a well-written conclusion can be ineffective if the delivery is not good. Conclusions often turn out bad because they weren’t practiced enough. If you only practice your speech starting from the beginning, you may not get to your conclusion very often because you stop to fix something in one of the main points, get interrupted, or run out of time. Once you’ve started your speech, anxiety may increase as you near the end and your brain becomes filled with thoughts of returning to your seat, so even a well-practiced conclusion can fall short. Practicing your conclusion by itself several times can help prevent this.

Key Takeaways

- The speech consists of an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. When organizing a speech, start with the body.

- Determine the main points of a speech based on your research and supporting materials. The main points should support the thesis statement and help achieve the general and specific purposes.

- The organizational patterns that can help arrange the main points of a speech are topical, chronological, spatial, problem-solution, cause-effect, and Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

- Incorporating supporting material helps fill in the main points by creating subpoints. As supporting material is added to the speech, citation information should be included so you will have the information necessary to verbally cite your sources.

- Organizing signposts help connect the introduction, body, and conclusion of a speech. Organizing signposts should be written using parallel wording to the central idea of each main point.

- A speaker should do the following in the introduction of a speech: get the audience’s attention, introduce the topic, establish credibility and relevance, and preview the main points.

- A speaker should do the following in the conclusion of a speech: summarize the importance of the topic, review the main points, and provide closure.

Exercises

- Identifying the main points of reference material you plan to use in your speech can help you determine your main points/subpoints. Take one of your sources for your speech and list the main points and any subpoints from the article. Are any of them suitable main points for your speech? Why or why not?

- Which organizational pattern listed do you think you will use for your speech, and why?

- Write out verbal citations for some of the sources you plan to use in your speech, using the examples cited in the chapter as a guide.

- Draft the opening and closing lines of your speech. Remember to tap into your creativity to try to engage the audience. Is there any way you can tie the introduction and conclusion together to create a “ribbon and bow” for your speech?

References

Lass-Hennemann, J., Linn K. Kuehl, André Schulz, Melly S. Oitzl, and Hartmut Schachinger, “Stress Strengthens Memory of First Impressions of Others’ Positive Perosnality Traits,” PLoS ONE 6, no. 1 (2011): 1.

Laws, E. L., Jennifer M. Apperson, Stephanie Buchert, and Norman J. Bregman, “Student Evaluations of Instruction: When Are Enduring First Impressions Formed?” North American Journal of Psychology 12, no. 1 (2010): 81.

Monroe, A. H., and Douglas Ehninger, Principles of Speech, 5th brief ed. (Chicago, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1964).

Winans, J. A., Public Speaking (New York: Century, 1917), 411.