13 Action Research for Practitioners

Phillip Olt

Definitions of Key Terms

- Action Research: An iterative approach to applied research, which can use a variety of social science research methods for the purpose of addressing a local problem of practice or continuous improvement.

- Applied Research: The systematic collection and analysis of data to generate new knowledge for a specific applied purpose.

- Collaborative Action Research (CAR): A type of action research when multiple practitioners addressing a shared issue of practice.

- Data: A plural term for facts or evidence collected; data may be both numerical and non-numerical.

- Educational Action Research (EAR): A type of action research specifically done in the field of education, which is broken into three sub-types of emancipatory, practical, and knowledge-generating.

- Method: A way of doing something; for examples, a survey is way of collecting quantitative data, and an interview is a way of collecting qualitative data.

- Methodology: Properly, “the study of methods;” in practice, a methodology is an over-arching approach to research that has coherent purpose, data collection methods, data analysis, and outcomes.

- Participatory Action Research (PAR): A type of action research that pairs practitioners (insiders) with professional researchers (semi-insiders/outsiders) to co-create knowledge for social change.

- Qualitative: An approach to social science research that focuses on the collection and analysis of data that provides deep insights into a phenomenon rather than generalization. Often, qualitative research is used in either an exploratory (giving preliminary insight to an un-/under-studied phenomenon) or explanatory (giving deeper insight to a previously-studied phenomenon) way.

- Quantitative: An approach to social science research that focuses on the collection and analysis of numerical data to consider relationships among variables. Often, quantitative research has the goal of producing generalizable results by performing statistical analysis of a small representative sample of the population and implying those results upon the full population.

- Research: A systematic approach to generating new knowledge situated within the body of knowledge for an area of study.

- Social Science Research: The scientific study of people, from individuals and relationships to society, which is situated within the existing body of knowledge; it is contrasted the approaches to studying humanity rooted in the natural sciences, philosophy, or humanities.

What is “action research”?

Recalling back to Chapter 1 “Foundations,” action research is defined relatively coherently across social science disciplines. As a basic, working definition in this text, action research is an iterative approach to applied research, which can use a variety of social science research methods for the purpose of addressing a local problem of practice or continuous improvement. Some key elements in that definition:

- iterative. Action research is not a one-and-done approach; rather, it is intended to be repeated over and over (perhaps indefinitely) in the same general sequence. Action research is most often described as a spiral or a cycle, wherein it repeats over and over with directionality toward improvement.

- can use a variety of social science research methods. Action research is not beholden to a single method or methodology. Originally and maybe most commonly, action research has primarily used qualitative methods without an overarching methodology (like ethnography). However, quantitative methods or multiple/mixed methods can absolutely be used as well. In the field of education (and specifically, teaching), quantitative methods may even be more common. For example, a teacher might use a pre-/post-test model for their data collection with one section of US History using the same pedagogical approach to a unit (control group) and another section of US History using a new pedagogical method for the same unit (experimental group).

- for the purpose of addressing a local problem of practice or continuous improvement. Whereas most formal research seeks to address broad problems for a broad audience or give deep insights into the same, action research very specifically addresses something local to the scholarly practitioner conducting the research. This should generally be something that the scholarly practitioner is directly involved with. It might look like a school counselor trying to understand why certain demographic groups at their school are less likely to see counseling support (and how to increase engagement by those groups) or this university professor trying to improve his courses and course materials.

The action research spiral or cycle can vary quite a bit in the details, but the concept and process are generally the same. While this chapter will introduce its own model, one other example to consider is Mertler’s (2024) organization: Planning, Acting, Developing, Reflecting [repeat indefinitely]. In this simple approach, the Planning Stage is focused on identifying a problem, searching what is known about it from research, and developing a plan to investigate an intervention. The Acting Stage involves doing the research plan and then gathering and analyzing data. In the Developing Stage, the scholarly practitioner comes up with an action plan based on the data analysis to improve practice, and then the Reflecting Stage is where they reflect on the action research plan and possibly share their results.

As a practical illustration, a high school history teacher might realize that a specific unit tends to be the hardest for their students. They might dig into their plans and perceptions of the topic. Then, after talking to peers, searching research literature, etc., they determine an alternate approach to teaching that unit. Then, they use multi-form pre/post tests to evaluate three sections of their history class using their old pedagogy and three sections using the new pedagogy. Tentative conclusions are reached about effectiveness, and the approach for the next school year is planned. Next year, that approach is evaluated against yet another approach.

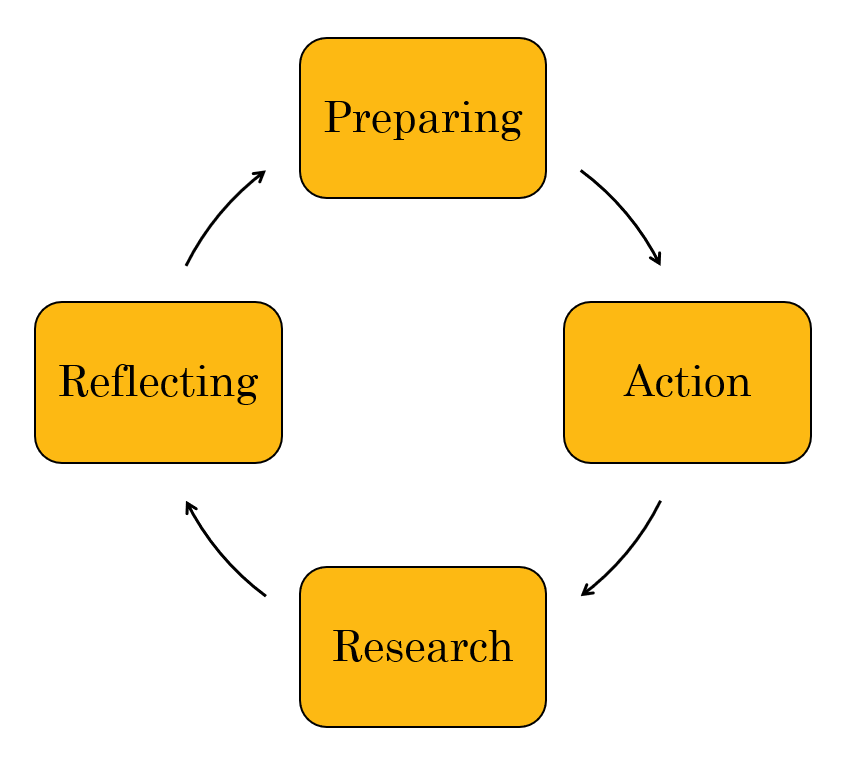

The Action Research Spiral / Cycle

There are a great number of ways to phrase and visualize action research. However, as Mertler (2024) observed, “Which model should you follow? Personally, I do not think it really matters, as I see them essentially as variations on the same theme (as evidenced by their shared elements)” (p. 18).

The two most common visualizations are of a spiral or a cycle, suggesting a repeated process that continues indefinitely. In the spirit of methodologists coining their own version of action research, I will share how I conceptualize action research as a cycle, though recognizing the significant overlap with others’ models. Thus, the four phases of the action research cycle are:

- Preparing

- Action

- Research

- Reflecting

Preparing

The Preparing Phase is, in this model, expansive, but it is all sensibly associated, as it is everything that happens before the “action” part of action research. It begins with an observation, usually of a problem of practice that needs to be addressed or an innovation that is desired to try. This is then followed by a thorough search to see what is known about that phenomenon—from discussions with peers to internet searches to a review of research literature. Finally, a plan is formulated, including both the desired intervention or innovation as well as how data will be gathered and assessed to evaluate efficacy. Note that, in action research studies, the research question(s) should be formulated specific to the setting and problem of practice.

Action

The Action Phase is rather straightforward, with the scholarly practitioner doing their planned intervention or innovation.

Research

The Research Phase is about collecting and analyzing data. The timing for collection will vary, depending on the research plan. There may be quantitative, qualitative, or mixed data generated through the research, which could be collected in a pre-/post-test model, all at the end, throughout, or really any variation of timing that makes sense (and, thus, could overlap the Action Phase).

Reflecting

So what? Even analyzed data are meaningless without taking the time to interpret and apply them. As action research is an applied research approach meant to be practical in nature, the scholarly practitioner needs to take time to consider what the data mean and what tentative conclusions for practice to draw from them. This is the Reflecting Phase.

The end of the Reflecting Phase, however, is the beginning of a new Preparing Phase. The tentative conclusion could be that there is no conclusion, as the data or design were insufficient; in that case, essentially the same action research study might be launched again in a new cycle. Perhaps, the new, better solution will now be compared to another potential solution in an ongoing attempt at continuous improvement; alternatively, the scholarly practitioner might be satisfied with their results on this specific topic and begin new action research on another problem or innovation.

Types of Action Research

As with many things in social sciences research methods and methodologies, action research continues to evolve. This is, however, just one chapter in a book for those getting started with social science research, and so every possible sub-type of action research will not be considered here. Broadly speaking then, the three most widely recognized types of action research are collaborative, participatory, and educational.

It is also important to note here that action research may be conducted as just basic action research without any type or sub-type. That is not an inferior choice at all. The types exist to extend action research not replace it.

Collaborative Action Research (CAR)

Sagor (1993) defined CAR as a sub-type of action research wherein, “we… begin developing an active community of professionals. The process described in this book is based on teams of practitioners who have common interests and work together to investigate issues related to those interests” (pp. 9-10). Whereas generally we might think of action research being done by a single practitioner to address an issue of their own practice, CAR occurs when multiple practitioners address a shared issue of practice. This might take the form of a group of community organizers investigating low voter turnout in their community or all 4th grade teachers at a school working to solve an issue in the shared 4th grade curriculum. In CAR, all researchers are practitioners and insiders to the problem.

Example CAR Study

Artiera-Pinedo, I., Paz-Pascual, C., Bully, P., Esponisa, M, & EmaQ Group. (2021). Design of the maternal website EMAeHealth that supports decision-making during pregnancy and in the postpartum period: collaborative action research study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(8), Art. e28855. https://doi.org/10.2196/28855

Participatory Action Research (PAR)

Cornish et al. (2023) defined and described PAR as:

…participatory action research (PAR) is a scholar–activist research approach that brings together community members, activists and scholars to co-create knowledge and social change in tandem. PAR is a collaborative, iterative, often open-ended and unpredictable endeavour, which prioritizes the expertise of those experiencing a social issue and uses systematic research methodologies to generate new insights. Relationships are central. PAR typically involves collaboration between a community with lived experience of a social issue and professional researchers, often based in universities, who contribute relevant knowledge, skills, resources and networks. PAR is not a research process driven by the imperative to generate knowledge for scientific progress, or knowledge for knowledge’s sake; it is a process for generating knowledge-for-action and knowledge-through-action, in service of goals of specific communities. The position of a PAR scholar is not easy and is constantly tested, as PAR projects and roles straddle university and community boundaries, involving unequal power relations and multiple, sometimes conflicting interests. (p. 2)

This definition and description is useful for our text here. PAR pairs practitioners (insiders to the setting and problem) with professional researchers (semi-insiders/outsiders). Ideally, those professional researchers have relevant knowledge and experience with the setting or phenomenon (making them semi-insiders). That might look like a recent middle school teacher who earned their doctorate and moved to a university in a new state doing PAR with one or more current middle school teachers nearby the university. However, that semi-insider status is not absolutely necessary, and so those professional researchers may just be true outsiders, providing methodological expertise and facilitation toward the shared goal. PAR is contrasted with CAR by the introduction of that semi-insider/outsider, as CAR is a collaboration among insiders only. Then, though the title does not explicitly suggest it, PAR is almost always used in an activist way in promoting social change, rather than addressing a specific, narrow problem. That social change might be at the organizational, city, etc. levels rather than society or worldwide, but it is still at a higher level than a single practitioner.

Example PAR Study

Feger, C., & Mermet, L. (2022). New business models for biodiversity and ecosystem management services: Action research with a large environmental sector company. Organization & Environment, 35(2), 252-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026620947145

Educational Action Research (EAR)

As implied in the title, EAR is action research in the field of education. Sometimes, there is a debate as to whether EAR is actually a type of action research or just a setting; however, EAR is still most widely recognized as a type and will be treated as such in this text. Newton and Burgess (2008) described three sub-types (or, as they call them, “modes”) of EAR: practical, emancipatory, and knowledge generating. These three sub-types are really distinguished by their purposes.

Mertler (2024) defined practical action research as a “type of action research focused on addressing a specific problem or need in a classroom, school, or similar community ” (p. 315). This is probably the most common sub-type, wherein, for example, a teacher applies action research to address an immediate problem of practice in their teaching.

However, those problems may (and often, do) have bigger causes, implications, and solutions. To that end, EAR applied to more social justice ends may be referred to as emancipatory. However, that emancipatory goal can be a “‘tough sell’ in schools as these approaches demand that practitioners take a hard look at the structures and social arrangements that dominate segments of the population, arrangements that they (teachers) might function to reinforce” (Newton & Burgess, 2008, p. 19).

Finally, knowledge-generating EAR is that which is done deliberately to both address a problem of practice and disseminate the report of that process broadly. This might, for example, be shared through publication in a scholarly journal or presented at a district-wide professional development.

Example EAR Study

Wastin, E, & Han, H. S. (2014). Action research and project approach: Journey of an early childhood pre-service teacher and a teacher educator. Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research, 16(2), Art. 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/2470-6353.1044

Key Takeaways

- Action research is a form of applied social research, which should be utilized by professionals in an ongoing cycle to address problems of practice or to promote continuous improvement.

- Action research can be done generally or in one of several specific types, largely based on whether the action research is (1) being done individually or with others and (2) whether those doing the research are insiders or a mix of insiders/semi-insiders/outsiders to the community of practice.

- Action research is conceptualized as a spiral or cycle that happens iteratively (over and over) to refine practice—Preparing, Action, Research, Reflecting, [repeat].

Additional Open Resources

Clark, J. S., Porath, S., Thiele, J., & Jobe, M. (2020). Action research. NPP eBooks. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/34

Chapter References

Artiera-Pinedo, I., Paz-Pascual, C., Bully, P., Esponisa, M, & EmaQ Group. (2021). Design of the maternal website EMAeHealth that supports decision-making during pregnancy and in the postpartum period: collaborative action research study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(8), Art. e28855. https://doi.org/10.2196/28855

Clark, J. S., Porath, S., Thiele, J., & Jobe, M. (2020). Action research. NPP eBooks. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/34

Cornish, F., Breton, N., Moreno-Tabarez, U., Delgado, J., Rua, M., de-Graft Aikins, A., & Hodgetts, D. (2023). Participatory action research. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 3, Art. 34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-023-00214-1

Feger, C., & Mermet, L. (2022). New business models for biodiversity and ecosystem management services: Action research with a large environmental sector company. Organization & Environment, 35(2), 252-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026620947145

Mertler, C. A. (2024). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators (7th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Newton, P., & Burgess, D. (2008). Exploring types of educational action research: Implications for research validity. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(4), 18-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690800700402

Sagor, R. (1993). How to conduct collaborative action research. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

Wastin, E, & Han, H. S. (2014). Action research and project approach: Journey of an early childhood pre-service teacher and a teacher educator. Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research, 16(2), Art. 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/2470-6353.1044