12 Multiple and Mixed Methods Research

Elliot Isom

Definitions of Key Terms

- Constructivism: A paradigm asserting that, whether objective truth exists or does not, it is only understood by humans as we construct it, which is driven by prior knowledge and social discourse.

- Cross-Cultural MMR: A growing application of MMR that balances standardized quantitative measures with culturally specific qualitative insights.

- Data Integration: The process of combining qualitative and quantitative data in MMR studies to ensure coherence and alignment in research findings.

- Interpretivism: A research paradigm which asserts that reality is socially constructed and cannot be understood through purely objective measurements (as would be common in positivist research).

- Mixed Methods Research (MMR): A distinct research methodology that intentionally integrates qualitative and quantitative approaches within a single study to provide a comprehensive understanding of a research question (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2018).

- Multiple Methods Research: A research approach that involves using more than one method of data collection or analysis within the same broad category (either qualitative or quantitative). Multiple Methods Research remains within a single methodological tradition, such as using different qualitative techniques (e.g., interviews and focus groups) or multiple quantitative approaches (e.g., surveys and experiments) without integrating both. (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010).

- Positivism: A research paradigm that believes objective truth exists and is knowable through (and only through) scientific methods.

- Post-Positivism: A research paradigm that acknowledges objective truth exists in a single reality but acknowledges the limitations of measurement and objectivity, allowing for some engagement between the researcher and participants.

- Pragmatism: The underlying philosophical foundation of MMR, advocating for the selection of research methods based on what works best to address a research question rather than strict adherence to a single paradigm.

- Reflexivity: The process of researchers critically examining their influence on the study, acknowledging biases, and ensuring credibility in qualitative and mixed methods research.

- Triangulation: A method in MMR where different data sources or analytical approaches are used to validate findings and enhance research reliability.

- Validity (in Multiple and Mixed Methods Research): The process of ensuring credibility and accuracy in findings through techniques such as convergence of results and method triangulation.

Mixed methods research has steadily gained traction in the social sciences for providing a comprehensive perspective on complex phenomena (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). By integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches, researchers can glean both numerical breadth and contextual depth, offering a fuller understanding of how interventions, policies, or environmental factors impact learning and well-being (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Mertens, 2015). Over time, early proponents recognized that the synergy between these distinct paradigms unlocks deeper insights than either method alone (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

This chapter introduces the philosophical foundations and major designs of mixed methods research, culminating with practical recommendations for ethically and effectively implementing designs in real-world settings. With these tools, emerging scholars can fully harness the potential of mixed methods to address the nuanced realities they face in their work.

Overview

Mixed Methods Research (MMR)

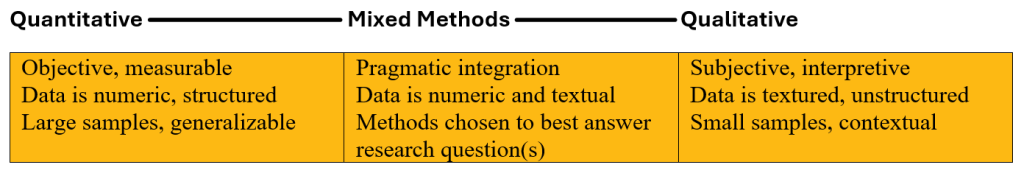

Mixed methods research (MMR) is a distinct research methodology that intentionally integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches within a single study to provide a comprehensive understanding of a research question (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2018). Unlike multiple methods research, which employs different methods within the same paradigm (e.g., multiple qualitative or multiple quantitative methods), MMR strategically combines qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis to leverage the strengths of both approaches (Fetters & Freshwater, 2015). The MMR process involves collecting, analyzing, interpreting and reporting data in typical fashion. However, the data involves both qualitative and quantitative evidence to answer the research questions (Dawadi et al., 2021). Much like other methods that are employed to research common themes, MMR was developed to address new emergent topics in the social sciences. Researchers using MMR have arrived at the conclusion that such an approach represents the best possible methodology to address the research problem.

History

The development of MMR designs is attached to and follows the progression of new research paradigms—a philosophical underpinning for beliefs surrounding the use and interpretation of research. For example, quantitative research methods commonly follow the idea of positivism in research, which believes truths can only be understood through interpreting numerical data. Interpretivism, in contrast, believes in multiple realities and the researcher can only gain an understanding through qualitative data, but the outcome is non-conclusive. Post-positivism follows the same principles, yet allows for more engagement between the researcher and participants. Post-positivistic researchers value the objectivity of the process (quantitative data), while acknowledging the value of the subjective experience (qualitative data) potentially adding another layer of understanding to the research outcome. If we combine our perspectives with objective (positivism) and subjective (interpretivism), the hope is to give new answers to research questions.

Why Use Mixed Methods?

As a researcher that uses an MMR design, you are acknowledging the value of both the positivism and interpretivism research paradigms. However, it is important to understand that, even though MMR covers a broader context of research, it may not always be the most productive strategy to use in a research endeavor. Therefore, it falls on the principal investigator to determine whether MMR is the best approach to design a study or would other approaches be more efficient. Given the determination to use MMR, the approach represents the most effective methodology to gain insight into a researched problem from multiple perspectives. MMR creates the conditions to expand studies, offering broader conclusions in areas that were otherwise devoid of new directions. The outcomes of MMR studies offer a greater breadth of conclusions, helping researchers to develop a more holistic picture of a particular phenomenon.

Dawadi et al. (2021) identified six major justifications for combining qualitative and quantitative methods for a research study:

- Expansion: Mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches broadens the scope of a study, providing both depth (through narratives and interviews) and breadth (through numerical data) to foster robust generalizations and nuanced insights (Creswell, 2003).

- Complementarity: Employing both methods acknowledges the distinct value each brings, producing synergy and reinforcing conclusions by enabling greater certainty and wider implications (Maxwell, 2016; Morgan, 2014).

- Combining Philosophies: Integrating the two paradigms bridges epistemological divides and offers a more complete, contextually rich understanding of a phenomenon, thereby opening avenues for deeper reflection and future inquiries (Tashakkori 2009; Lund, 2012).

- Offsetting Weaknesses: By leveraging the strengths of one approach to compensate for the limitations of the other, mixed methods research increases methodological rigor and accuracy in conclusions (Ivankova & Plano Clark, 2018).

- Enhanced Validity: Converging results from different data sources enriches the validation process, leading to more credible findings and enhancing the reliability of interpretations (Tashakkori 2009; Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).

- Method Development: A sequential MMR design allows researchers to refine and shape the second method based on initial results, creating more targeted and meaningful follow-up investigations (Ivankova & Plano Clark, 2018).

While mixed methodologies can be more time consuming and complex, they afford researchers more developed opportunities to explore a research topic. Additionally, research conducted under an MMR framework offers the prospect to better validate outcomes, presenting more credibility to research in the social science fields.

Multiple Methods Research

While Mixed Methods Research (MMR) integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches within a single study, “multiple methods research” refers to the use of more than one method within the same methodological tradition—either qualitative or quantitative. This approach allows researchers to explore a research problem more comprehensively by leveraging different data collection and analysis techniques within a single paradigm (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010).

Characteristics of Multiple Methods Research

- Within-Paradigm Application: Unlike MMR, which blends qualitative and quantitative methodologies, multiple methods research remains entirely within a single research paradigm (e.g., exclusively qualitative or quantitative).

- Diverse Data Collection Techniques: Researchers may employ multiple qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, ethnographic observations, and focus groups) or multiple quantitative approaches (e.g., surveys, experiments, and secondary data analysis) to gain deeper insights.

- Enhanced Rigor and Reliability: Using multiple methods within the same paradigm helps strengthen the credibility of findings by allowing methodological triangulation—comparing different data sources or analytical approaches to validate results (Flick, 2018).

- Sequential or Parallel Implementation: Similar to MMR, multiple methods research can be conducted in sequential (where one method informs the next) or parallel (where methods are applied simultaneously) designs (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Distinguishing Multiple Methods Research from Mixed Methods Research

A common misconception is that multiple methods research and mixed methods research are interchangeable. The primary distinction lies in the integration of data. Multiple Methods Research does not integrate qualitative and quantitative methods but rather employs different techniques within the same methodological framework. In contrast, mixed methods explicitly combines qualitative and quantitative data to enhance the breadth and depth of findings (Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007).

Multiple methods research provides a valuable approach for deepening methodological rigor and broadening the scope of inquiry within either qualitative or quantitative traditions. However, researchers must ensure they select the appropriate methodological framework to align with their study’s objectives. Understanding the differences between multiple methods research and mixed methods research is crucial for researchers aiming to apply the most effective strategy for their research questions.

Philosophical and Theoretical Foundations

Doing What Works

The pragmatism that underpins mixed methodology describes the intent to find whatever works to gain understanding of the phenomenon. As we’ll see in the next section there are many common designs for constructing mixed methods studies. These designs seek to blend quantitative and qualitative using different dimensions and longitudinal factors that incorporate the strategies found in other research methodologies.

| Paradigm | View of Reality | Interpretation of Data | Research Implications | Primary Research Methodology |

| Post-positivism | One reality, imperfect understanding | Objective, measurable | Structured designs; focus on validity and reliability | Quantitative |

| Constructivism | Multiple realities; socially constructed understanding | Subjective, co-created knowledge | Flexible, focused on participant’s context | Qualitative |

| Pragmatism | Reality as both singular and multiple; understanding depends on the inquiry | Produced through practical and applied means | Chosen based on “what works”; utilizes multiple data forms | MMR |

Research Designs

Common Mixed Methods Designs

While MMR designs have shown flexibility to create conditions for “what works” depending on the context of the study, recent literature has demonstrated a push to find a standardized approach to MMR designs. Historically, however, there have been a number of trending designs that are dependent upon the research case rather than one design to fit any study. Rather than describe a singular design to conduct an MMR study, this text seeks to present you with multiple design styles to help you discern the use of MMR in any research study. It is important to understand that data in an MMR design works conjunctively rather than separately to create a holistic outcome.

| Design |

Description | Strengths | Challenges | Example |

| Convergent Parallel Design | Collects quantitative and qualitative data concurrently; analyzes separately and integrates findings to compare for convergence or divergence | Efficient in time-limited settings; allows for cross-validation of data | Difficult to resolve discrepancies between data types; requires expertise in both methods | Studying the impact of mindfulness on student anxiety using surveys and focus groups conducted simultaneously |

| Explanatory Sequential Design | Begins with quantitative data collection and analysis, followed by qualitative research to explain quantitative results | Clarifies statistical trends with rich qualitative insights | Time-consuming; requires participant commitment for follow-up studies | Evaluating Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) effectiveness using depression scales followed by interviews with participants |

| Exploratory Sequential Design | Starts with qualitative data collection to explore a phenomenon, followed by quantitative data to generalize findings | Explores new topics deeply before confirming generalizability | Longer research timeline; requires expertise in qualitative analysis | Exploring teacher strategies for student motivation via interviews, then developing a survey to assess usage across schools |

| Embedded Design | One type of data (qualitative or quantitative) serves as the primary method, with the other embedded to support the main findings | Provides additional context and depth to dominant data type | Risk of imbalance if embedded data is not well integrated | Assessing Social/Emotional Learning (SEL) programs by using discipline records and standardized tests, with embedded teacher/student interviews |

| Multiphase Design | Data collection occurs in multiple phases over time, using different data types to build upon prior findings for a comprehensive understanding | Captures long-term changes and complex relationships over time | Requires significant planning; logistical challenges in multi-phase data collection | Studying student behavior changes over multiple years using various data collection methods at different phases |

| Transformative and Participatory Design | Focuses on social justice, co-designing research with participants, and addressing power dynamics in vulnerable populations | Empowers participants and facilitates actionable social change | Limited standardization; ethical concerns and potential mistrust among participants | Examining student-led mental health initiatives where students co-design programs and contribute to data collection and analysis |

Common Multiple Methods Designs

Multiple methods research involves the use of two or more research methods within a single study to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a research question. Unlike mixed methods research, which integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches, multiple methods research often employs methods within the same paradigm (either qualitative or quantitative) but in distinct ways. These designs help researchers validate findings, enhance reliability, and offer multiple perspectives on a phenomenon. The table below outlines several common multiple methods research designs, highlighting their descriptions, strengths, weaknesses, and real-world applications.

| Design |

Description | Strengths | Challenges | Example |

| Sequential Qualitative | Researchers use one qualitative method first (e.g., interviews), then follow up with another (e.g., focus groups) to refine or expand findings | Provides depth and allows for refining themes before final conclusions | Time-consuming and may require re-evaluating earlier findings | A study first conducts individual interviews to explore patient experiences, followed by focus groups to refine common themes |

| Sequential Quantitative | A study begins with one quantitative method (e.g., surveys) and follows up with another (e.g., experiments) for further validation | Strengthens generalizability and ensures statistical robustness | Risk of initial survey biases affecting subsequent data collection | A survey measures attitudes about online learning, followed by an experiment testing students’ engagement with different learning formats |

| Parallel Qualitative | Two or more qualitative methods are conducted simultaneously but analyzed separately to provide multiple perspectives on the same phenomenon | Enhances credibility by triangulating data from different sources | Requires careful alignment of methods and theoretical consistency | A study uses ethnographic observations and in-depth interviews simultaneously to examine workplace culture |

| Parallel Quantitative | Two or more quantitative methods (e.g., experiments and secondary data analysis) are conducted simultaneously and analyzed separately | Increases validity by comparing multiple data sources and strengthens reliability | Managing large datasets and ensuring comparability can be challenging | An experiment examines customer behavior in an online store, while sales data analysis evaluates purchasing trends |

| Embedded Qualitative | A primary qualitative method is supplemented with another qualitative technique to provide deeper contextual understanding | Provides rich insight into experiences and enhances interpretive depth | Risk of overcomplicating the analysis if findings conflict | A case study on teacher burnout includes document analysis of teacher journals to provide additional context |

| Embedded Quantitative | A primary quantitative study is supplemented with an additional quantitative method for contextualization or deeper insight | Strengthens statistical findings with additional layers of data | Requires a well-structured research design to avoid redundancy | A randomized controlled trial on medication effectiveness is supplemented with health records analysis to assess real-world impact |

Planning a Mixed Methods Study

There are several considerations researchers must make before deciding whether a study would be appropriate for a mixed methods design. First, it would behoove a researcher to determine what the purpose of the study is and, if wanting to use a mixed methods design, what is it about the study that would be mixed? An important caveat to decide upon an MMR design is wanting to provide a holistic understanding of a phenomenon for which current research is inconclusive and/or disjointed (Venkatesh et al., 2016). If moving forward with an MMR design, the areas below inform the considerations needed to plan an MMR study (derived from Kajamaa et al., 2020):

| Question to be asked in planning | Explanation and prompts |

| What is the overarching aim of the study? | Mixed-methods studies, by definition, are often designed with a specific aim that can guide the final study design: discuss with the research team whether the overarching aim is theory building (explaining, exploring or describing phenomena) or hypothesis testing. |

| Which is the dominant method? | In some mixed-methods studies the methods are equally weighted but often they are not. It is worth making this explicit. Nested or embedded designs refer to where there is a smaller data set collected within a larger study for a specific purpose. |

| Is the data collection sequential, in parallel or convergent? | Research designs may be described as sequential (one after the other), in parallel (happening concurrently but separately, with integration occurring later) or convergent (happening concurrently and with the data sets interacting). |

| At what stage does the integration of the two methods occur? | It is important to be clear about whether, when, to what extent and how integration was achieved in the methodology section of the study. |

| Is the qualitative element explanatory or exploratory? | The qualitative element of the mixed-methods research may have a range of different purposes, such as explaining previous findings or exploring a phenomenon. |

Formulating Research Questions

One of the advantages of MMR designs is its’ ability to allow researchers to craft explanatory research questions, which are important to be able to make inferences rather than just observations. Inferences are important to gain an understanding of a phenomenon versus an objective observation.

Venkatesh et al. (2016) identified four possible dimensions to MMR questions in design: 1. Rhetorical Style—Format: Questions, Aims, and/or Hypotheses – This dimension refers to the way research questions are structured and presented within a study, 2. Rhetorical Style—Level of Integration – This refers to how closely the qualitative and quantitative research questions are connected within a mixed methods study, 3. The Relationship of Questions to Other Questions: Independent or Dependent – This dimension focuses on whether research questions stand alone or are interrelated within a study. Which could be either independent questions (questions do not rely on each other and investigate separate but related aspects of a phenomenon) or dependent questions (Research questions are linked, meaning that one question depends on another for context or explanation), and 4. The Relationship of Questions to the Research Process: Predetermined (Established at the beginning of the study and remain unchanged) or Emergent (Developed during the research process, particularly in qualitative or flexible mixed methods designs. These questions adapt based on initial findings).

Sampling Strategies

In mixed methods research, sampling strategies vary depending on the data type. Purposeful sampling is commonly used in qualitative research, allowing researchers to select participants based on their ability to provide rich, in-depth information about the phenomenon under study (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). In contrast, quantitative research often relies on probability sampling techniques, such as random sampling, to ensure a representative and generalizable sample (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). Mixed methods research integrates multiple sampling methods, such as selecting survey participants randomly for generalizability while purposefully choosing interview participants for depth (Ivankova & Plano Clark, 2016).

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection procedures involve both quantitative and qualitative methods, often requiring careful sequencing. Quantitative methods include surveys, standardized tests, and rating scales, which provide numerical data for statistical analysis (Hirose & Creswell, 2023). Qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups, and observations, offer rich contextual insights (Maxwell, 2016). The timing of data collection can be concurrent (collecting both types simultaneously) or sequential (one phase informing the next), depending on the study’s goals (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis techniques in mixed methods involve both statistical and thematic approaches. Quantitative analysis uses descriptive (e.g., means, frequencies) and inferential statistics (e.g., t-tests, regression) to identify patterns and relationships (Timans et al., 2018). Qualitative analysis often employs coding, thematic analysis, or grounded theory to identify key themes and narratives (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The integration of findings occurs through triangulation, side-by-side comparison, or narrative interpretation, helping researchers corroborate and contextualize numerical and textual data (Ivankova & Plano Clark, 2018).

Data Integration Strategies

Data integration strategies ensure a comprehensive interpretation of mixed methods data. Merging data allows researchers to present qualitative and quantitative findings side by side for direct comparison (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). Connecting data involves using findings from one phase to inform the next, such as conducting interviews to explain surprising survey results (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). Embedding data prioritizes one method while using the other to provide additional insight, such as a primarily quantitative study supplemented with qualitative narratives for context (Ivankova & Plano Clark, 2018). These strategies enhance the depth and validity of mixed methods research.

Quality and Validity in MMR

Determining rigor in research designs is a crucial step to determine how much trust viewers can place in the outcome of research. Both quantitative and qualitative methods have longstanding means of determining various elements of rigor. Mixed methods designs, on the other hand, are newer approaches to research, and therefore, the means of establishing rigor are still being understood. Ultimately, we always want to be asking if the study is good enough to be trusted and engaging in ways to evaluate methodologies used / potential bias to broadcast to others how much we can trust the results. In MMR, since we’re combing two approaches, we’ve identified two areas to assess to determine some basic validation (Harrison et al., 2020). First, how reliable are the strategies we used to combine quantitative and qualitative data (ensuring integration quality), and second, how are we managing the analysis of qualitative data (reflexivity and researcher positionality)?

| Common reporting and validation strategy in MMR | Description |

| GRAMMS Framework | The Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) is a widely recognized framework for reporting rigor in MMR. Researchers using this framework report justification, design type, mono-method components, data integration, limitations, and insights gained from data mixing (Harrison et al., 2020). |

| Holistic Quality | Beyond GRAMMS, holistic quality in MMR considers factors such as sample size, instrument reliability, and overall study coherence (O’Cathain, 2020). |

| Integration | The core of MMR, integration, involves mixing qualitative and quantitative data. High-quality integration includes presenting complete data strands, justifying integration, and synthesizing results for a merged comparison (Harrison et al., 2020). |

| Reflexivity | Reflexivity focuses on the qualitative aspects of MMR, ensuring reliability through researcher self-reflection, triangulation, and articulating the justification behind the MMR design. Researchers must also provide insights post-data integration (O’Cathain, 2020). |

Ethical Considerations in Multiple and Mixed Methods Research

While general research ethics were discussed in a previous chapter, ethical considerations within these MMR designs are complex due to the convergence of qualitative and quantitative approaches with their own unique sets of ethical challenges. Issues of informed consent, confidentiality, and the integration of the two approaches must all be addressed while participants are made aware of the ways their information will be applied with the various approaches. Power relationships can also impact the response of participants, especially with vulnerable groups within the realms of counseling, education, nursing/medicine, or cross-cultural research. Therefore, it is important to preserve the well-being of participants, especially within the emotionally charged research environment. Ethical MMR necessitates meticulous planning, culture sensitivity, and a dedication to the minimization of harm while maximizing the research integrity and impact.

Informed Consent Across Methods

Mixed methods research (MMR) poses specific challenges to the attainment of informed consent due to the multifaceted approaches to data collection involved. In contrast to single-method research, MMR necessitates that the participants are made aware of the way their data will be merged between qualitative and quantitative elements that could include varying levels of disclosure and anonymity. For example, survey information can usually be anonymized while the recordings of the interviews or case studies might include information that creates greater confidentiality concerns (Dawadi et al., 2021). It is the responsibility of the researchers to properly inform the participants about the way personal information is kept, secured, and connected to avoid the participants being kept in the dark about the possible threats and rewards of their participation. Ethical concerns also include confidentiality of the data, especially within counseling or educational environments where personal information might be revealed. Researchers need to have measures to avoid revealing identities unintentionally while triangulating with numeric information (Wisdom & Creswell, 2013).

Last, working with vulnerable groups within schools, counseling clinics, hospitals, prisons, or oppressed communities requires a culturally aware and ethically driven approach to MMR. Power relationships between participants and researchers can be increased with the use of mixed methods since qualitative research entails closer personal interactions while quantitative research can impose hierarchical frameworks with the use of standard measures (Bryman, 2012).

Challenges & Limitations

Dawadi et al. (2021) noted that MMR, while delivering more answers to traditional research questions, can often fail in achieving its’ goal to produce conclusive outcomes. The risk of clear research outcomes in MMR studies lie in its’ design to mix data, which presents a number of additional threats, more so than traditional methods. Additionally, the act of mixing up data presents a direction of too many ambiguous research questions, Creswell (2003) warned. Therefore, the multiple and MMR approaches are not recommended for novice researchers, and those wanting to apply the method should seek further training and experience under seasoned researchers (Dawadi et al., 2021). There are a number of common practical challenges and limitations to MMR designs, and Dawadi et al. (2021) summarized them as follows:

| Common Risk/Limitation in MMR | Description |

| Cost and time | MMR can be lengthy and expensive, often exceeding budgets and research timelines. |

| Difficulties integrating data | Integrating data can be complex, with limited guidance in existing literature. |

| Conflicting philosophies | Differences in quantitative and qualitative methodologies can create biases in data interpretation. |

| Retaining quality in data integration | One dataset may overpower the other, diminishing its independent value. |

| Incorrect design decisions | Choosing the wrong MMR design can impact study outcomes and data prioritization. |

Criticisms of MMR Designs

Conflicting Philosophies

Mixed methods research (MMR) has been widely adopted as an approach to integrating qualitative and quantitative methodologies to address complex research questions. However, it has also been subject to significant criticism. One major critique of MMR revolves around its conflicting philosophies for conducting research. As Dawadi et al. (2021) highlighted, MMR combines elements from positivism (which assumes a singular, objective reality) and interpretivism (which embraces multiple, socially constructed realities). Critics argue that these paradigms are incompatible, making it difficult to reconcile their underlying assumptions within a single study (Maxwell, 2016). Incompatible paradigms can lead to methodological inconsistencies, where researchers struggle to maintain coherence in their designs, data collection, and interpretation. Additionally, some scholars contend that MMR is often driven by the motivations of the researcher rather than being grounded in the foundations for successful research (Guba, 1987; Smith, 1983).

Logistical Traps

Another significant critique of MMR is its practical and logistical challenges. The integration of qualitative and quantitative data requires researchers to be proficient in both methodologies, which can be particularly demanding (Wisdom & Creswell, 2013). Issues such as the time-consuming nature of data collection, difficulties in integrating findings from different methodological traditions, and challenges in ensuring quality and rigor across both approaches have been widely documented (David et al., 2018; Dawadi, 2019). Furthermore, the potential for conflicting results between qualitative and quantitative strands can complicate data interpretation, sometimes leaving researchers unsure of how to synthesize divergent findings (Salehi & Golafshani, 2010). The additional burden of justifying methodological choices and ensuring that the study does not become excessively broad or unfocused can further hinder the effective application of MMR (Wilkinson & Staley, 2019). Despite these criticisms, proponents argue that with careful design and clear justification, MMR can offer an approach to complex research problems by leveraging the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods (Bryman, 2012; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Looking Ahead: Trends and Future Directions

Technological Advances

The rise of digital tools and software has significantly enhanced the ability to apply MMR designs, allowing for better integration of qualitative and quantitative data. Advanced software platforms such as NVivo, Dedoose, MAXQDA, and ATLAS.ti now support integrated data analysis, enabling researchers to more accurately link qualitative data with quantitative variables. Similarly, statistical tools like R and SPSS have features that utilize mixed methods approaches (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). These tools reduce the complexity of integrating diverse datasets, making MMR more efficient and less prone to risks outlined above. Additionally, innovations in data visualization are improving how mixed methods findings are presented. Interactive dashboards, heat maps, and AI-assisted visual analytics allow for the simultaneous representation of qualitative themes and quantitative trends, enabling researchers to better articulate their findings.

Global and Cross-Cultural Expansion

Internationally, MMR is increasingly being adopted as a commonly used framework for research. As research increasingly extends beyond Western frameworks, MMR allows scholars to balance standardized quantitative measures with culturally specific qualitative insights. This adaptability is particularly valuable in global health, education, and community development studies, where researchers must account for local traditions, languages, and social norms (Bryman, 2012). One challenge in international MMR is ensuring that methodological approaches are culturally sensitive and contextually relevant. Researchers must carefully adapt survey instruments, interview protocols, and data interpretation techniques to reflect the values and lived experiences of different populations. Additionally, ethical considerations in cross-cultural research require researchers to prioritize community engagement and participatory methodologies, ensuring that findings are meaningful and actionable within local settings (Wisdom & Creswell, 2013).

Key Takeaways

- Mixed methods and multiple methods approaches to social research are similar but distinct.

- MMR provides a rich way for researchers to approach complex, multifaceted problems by utilizing both qualitative and quantitative approaches, facilitating a deeper, richer understanding of research problems by enabling the capture of both numeric patterns and rich descriptive narratives (Dawadi et al., 2021).

- To best leverage the value of MMR, researchers need to implement best practice in the design, conduct, and reporting of the research—guaranteeing methodological rigor, ethics integrity, and transparent integration of results. Furthermore, a dynamic, adaptive approach to research maximizes the flexibility of MMR to allow researchers to adapt the approach to emerging results.

- With the flexibility of MMR, researchers can conduct research that not only increases academic knowledge but also informs practical applications within the social sciences.

Additional Resources

MMR Data Analysis Software

Atlas.ti (https://atlasti.com/)

Dedoose (https://www.dedoose.com/)

MAXQDA (https://www.maxqda.com/)

NVivo (https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/)

SPSS (https://www.ibm.com/spss)

R (https://www.r-project.org/) – free

Discussion of Applied MMR to Social Science Professions

Alhassan, A. I. (2024). Analyzing the application of mixed method methodology in medical education: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 24, Art. 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05242-3

Examples of MMR

Fàbregues, S., Escalante-Barrios, E. L., Molina-Azorin, J. F., Hong, Q. N., & Verd, J. M. (2021). Taking a critical stance towards mixed methods research: A cross-disciplinary qualitative secondary analysis of researchers’ views. PLOS ONE, 16(7), Art. e0252014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252014

Fryer, C. S., Seaman, E. L., Clark, R. S., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Mixed methods research in tobacco control with youth and young adults: A methodological review of current strategies. PLOS ONE, 12(8), Art. e0183471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183471

Kramer, B., Jones, D., & Broadbent, C. (2023). Teacher autonomy and agency during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4450519

Schoonenboom, J. (2023). The fundamental difference between qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 4. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3986

Chapter References

Alhassan, A. I. (2024). Analyzing the application of mixed method methodology in medical education: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 24, Art. 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05242-3

Almeida, F. (2018). Strategies to perform a mixed methods study. European Journal of Education Studies, 5(1), 137-151. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1406214

Bletscher, C. G., & Galindo, S. (2024). Challenges with using transformative mixed methods research among vulnerable populations: Reflections from a study among US-resettled refugees. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 18(2), 165-190.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2012). Quantitative data analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A guide for social scientists. Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

David, S. L., Hitchcock, J. H., Ragan, B., Brooks, G., & Starkey, C. (2018). Mixing interviews and Rasch modeling: Demonstrating a procedure used to develop an instrument that measures trust. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(1), 75-94.

Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., & Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion on its Types, Challenges, and Criticisms. Journal of Practical Studies in Education, 2(2), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.46809/jpse.v2i2.20

Fàbregues, S., Escalante-Barrios, E. L., Molina-Azorin, J. F., Hong, Q. N., & Verd, J. M. (2021). Taking a critical stance towards mixed methods research: A cross-disciplinary qualitative secondary analysis of researchers’ views. PLOS ONE, 16(7), Art. e0252014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252014

Fetters, M. D., & Freshwater, D. (2015). The 1 + 1 = 3 integration challenge in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(2), 115-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815581222

Fryer, C. S., Seaman, E. L., Clark, R. S., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Mixed methods research in tobacco control with youth and young adults: A methodological review of current strategies. PLOS ONE, 12(8), Art. e0183471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183471

Guba, E. G. (1987). What have we learned about naturalistic evaluation?. Evaluation practice, 8(1), 23-43.

Harrison, R. L., Reilly, T. M., & Creswell, J. W. (2020). Methodological rigor in mixed methods: An application in management studies. Journal of mixed methods research, 14(4), 473-495.

Hirose, M., & Creswell, J. W. (2023). Applying core quality criteria of mixed methods research to an empirical study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(1), 12-28.

Ivankova, N. V., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Teaching mixed methods research: using a socio-ecological framework as a pedagogical approach for addressing the complexity of the field. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(4), 409-424.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26.

Kajamaa, A., Mattick, K., & de la Croix, A. (2020). How to… do mixed‐methods research. The Clinical Teacher, 17(3), 267-271. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13145

Leah, V. (2019). Maintaining my relative’s personhood: A mixed method design (Doctoral dissertation, Buckinghamshire New University (Awarded by Coventry University)).

Lund, T. (2012). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: Some arguments for mixed methods research. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 155-165.

Maxwell, J. A. (2016). Expanding the history and range of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(1), 12-27.

Mertens, D. M. (2015). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (4th ed.). SAGE.

Morgan, D. L. (2014). Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qualitative inquiry, 20(8), 1045-1053.

Munce, S. E. P., Guetterman, T. C. & Jaglal, S. B. (2021). Using the exploratory sequential design for complex intervention development: Example of the development of a self-management program for spinal cord injury. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15(1) 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689820901936

O’Brien J. E., Brewer K. B., Jones L. M., Corkhum J., Rizo C. F. (2021). Rigor and respect: Recruitment strategies for engaging vulnerable populations in research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17-18), NP17052-NP17072. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211023497

O’Cathain, A. (2020). Mixed methods research. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 169-180). John Wiley & Sons.

Salehi, K., & Golafshani, N. (2010). Commentary: Using mixed methods in research studies: An opportunity with its challenges. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 4(3), 186-191.

Schoonenboom, J. (2023). The fundamental difference between qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 4. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3986

Smith, J. K. (1983). Quantitative versus qualitative research: An attempt to clarify the issue. Educational researcher, 12(3), 6-13.

Tashakkori, A. (2009). Are we there yet? The state of the mixed methods community. Journal of mixed methods research, 3(4), 287-291.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2010). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of mixed methods research, 1(1), 77-100.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE.

Timans, R., Wouters, P., & Heilbron, J. (2019). Mixed methods research: what it is and what it could be. Theory and Society, 48, 193-216.

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., & Sullivan, Y. W. (2016). Guidelines for conducting mixed-methods research: An extension and illustration. Journal of the Association for Information systems, 17(7), 435-494. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00433

Wilkinson, I. A., & Staley, B. (2019). On the pitfalls and promises of using mixed methods in literacy research: Perceptions of reviewers. Research Papers in Education, 34(1), 61-83.

Wisdom, J., & Creswell, J. W. (2013, March). Mixed nethods: Integrating quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis while studying patient-centered medical home models. PCMH Research Methods Series, 13.