5 The Research Process

Phillip Olt

Definitions of Key Terms

- Applied Research: The systematic collection and analysis of data to generate new knowledge for a specific applied purpose.

- Basic Research: The systematic collection and analysis of data to generate new knowledge for the sake of generating new knowledge, regardless of the current or future utility of that new knowledge.

- Delimitation: Factors that define the limits of your study, which is inherent to the design and scope of the study.

- Hypothesis: An assumption to be tested that attempts to explain the relationship between certain variables.

- Limitation: A factor that limits your study, usually arising during the study and outside of researcher control.

- Positivism: The belief that objective truth exists and is knowable through (and only through) scientific methods.

- Post-Positivism: An extension of Positivism, holding that objective truth exists but is only knowable by humans in part and contingently.

- Problem Statement: The explanation of a current human/social problem to be addressed through applied social research

- Purpose Statement: The statement by a researcher how the purpose of their research study, usually articulating how they hope to help address the problem in the problem statement

- Research Question: A clear and precise question about a singular item to be measured through the research study

Getting Started with Getting Started

As a way of illustration, let me share about my work in writing this textbook. I served as the editor, as well as authoring the front matter, back matter, and eight of the chapters. For some reason, this chapter was a mental block for me. Every time I went to work on it, I found an excuse not to, whether that was writing another chapter or doing something altogether different. And so, this chapter sat completely not worked on for half a year. I would scroll past it only to feel anxiety and embarrassment for not doing anything with it. It is important to note here too that no one else could even see what I had or had not worked on throughout the process; that was all in my own head, heart, and soul. Eventually, I became self-aware of how much anxiety I was having about writing this chapter, and great irony dawned on me—I was struggling greatly to get started writing a chapter about helping people to get started writing. Thankfully, this realization also proved to be the spark I needed to get in here and write this very chapter.

I share this here for a couple of reasons. First, everyone (perhaps an over-generalization) struggles with scholarly writing. Whether we call that writer’s block, anxiety, or whatever, it is not just you. Second, the most important thing to getting started with research and/or writing is to start researching and/or writing.

So, whatever is holding you back from getting started, follow the Nike slogan—Just Do It! I do, however, recognize that is rarely easy, even evidenced here by my own struggle of postponing work on this chapter. However, I felt significantly better once I started working on this, and it is very likely you will feel that way too after you take the first steps on whatever it is you are not making progress on.

Preliminary Refinements

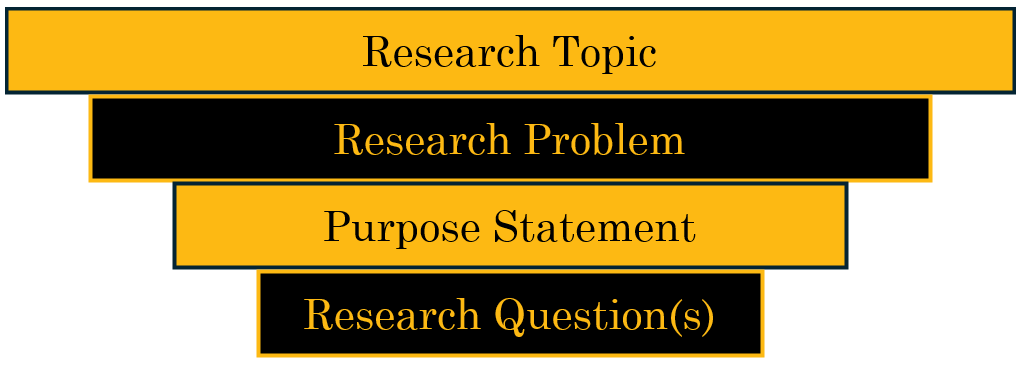

The process of getting started on a new research project is best seen as refinement from broad → specific, with the preliminary steps going from: Research Topic, Research Problem, Purpose Statement, to Research Question(s). This process is generally described in a similar fashion across social research methodologists and textbooks (for example, see Creswell & Guetterman, 2019).

Preliminary Step 1: Selecting a Research Topic

The broadest of the four steps, a researcher must first select their topic. Now, “broadest” should not be interpreted to the extreme, such as, “my topic is ‘humans;'” however, it is somewhat squishy to define in an absolute sense. So, here are some examples of topics for social research:

- Microeconomics of family budgeting

- Poverty in America

- Science education

Exactly where one draws the line on what is technically a “topic” really does not matter much in practice though, as the research problem (see below) is really the broadest/highest level that one sees articulated with focus in a research study. Even when a research problem is included in the write-up of a study, it is rarely labeled that way but rather implied through the Introduction and/or Literature Review sections.

That, however, still leaves the question of how one selects a topic. Cozby (2007) proposed five sources of ideas: common sense, observation of the world around us, theories, past research, and practical problems. Mills and Gay (2016) listed four sources: theories, personal experiences, previous studies, and library searches. I believe, however, that this is best distilled down to two categorizations.

- Sometimes ideas come from existing research, whether that is from reading published literature or attending an academic conference or extending a descriptive theory or even a dissertation supervisor compelling a topic closely related to their expertise and existing research.

- Often, however, it comes from personal experience. That might look like, “I was a high school social studies teacher, so now I’m interested in researching that.” Or, it might be researching a demographic group of which you are/were a member (ex., “I am a Native American, and now I am interested in researching the lived experiences of Native Americans on reservations”).

Some scholars, however, look down upon people researching things related to their own experience, pejoratively called “me-search” as a play on words. It can be cast as inferior, because the researcher is then not bringing an unbiased perspective. However, as social research increasingly skews away from positivism and post-positivism (which will be discussed more in subsequent chapters), me-search has become far more accepted as just “research” and maybe even the norm.

Example Research Topic

Here, and in the subsequent sections on the other preliminary steps of the research process, I will again utilize my dissertation to illustrate (Olt, 2018). Often, in journal article-length manuscripts (which is most published social science research), the topic and research problem are implied rather than stated as such with dedicated content. In that study, my research topic was:

regulatory compliance in higher education

Preliminary Step 2: Articulating a Research Problem

Applied research is far more common than basic research in the social sciences, and applied research must have a problem to address. Chappell and Voykhanksy (2022) described such problems as, “specific challenges… needing systematic and objective investigation to find a solution, test a theory, determine cause and effect, or find effective strategies that address the issue” (p. 26). Defining a research problem is, in applied research, the first step of refinement below the topic, and as such, it narrows the focus from “all of <the thing>” to “a specific facet of <the thing>.” Here again, what problem to research inside of a topic is determined by the researcher using the existing research and/or the researcher’s interests or experiences. The research problem (or “problem statement”) is often implied in journal articles, rather than written explicitly, somewhere in the Introduction and/or Literature Review sections; however, it will likely have its own dedicated section in a thesis or dissertation.

The content of a problem statement will vary. However, it should lay the groundwork for why the study is needed. That commonly means explaining what the problem is and how it is not addressed adequately in this existing research.

Example Research Problem

Below is the paragraph-length problem statement from my dissertation:

At a small liberal arts college (SLAC), faculty and staff members are often stretched to meet the same compliance requirements as an institution classified as R1–Highest Research Activity by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education (2017), although their funding and staffing may be far less. The R1 institution may be burdened, but it is large enough to benefit from the size of its staff and has a flow of research grants and state funding. A SLAC, especially if private, is structured and funded quite differently. Bok (2013) juxtaposed multibillion dollar endowments at an R1 against the struggle for survival at many SLACs. Commonly, a collegial institution as described by Birnbaum (1998), a SLAC is generally centered on teaching and close relationships with students, without the research emphasis present at other types of institutions (Oakley, 2005). However, as that SLAC would have a science lab in some form for teaching scientific reasoning in the general education curriculum and supporting majors in the sciences, it will have to comply with most of the same regulations as any collegiate lab, albeit at a smaller scale than the R1 university. Rather than having a staff of faculty members, scientists, post-doctoral researchers, graduate assistants, and undergraduate students on which to apportion compliance activities, such a lab may be staffed by a part-time employee and the teaching-focused professors who float through. (Olt, 2018, pp. 1-2)

After this, I elaborated on how this fell into a gap in the existing research literature and thus would have a positive benefit on the problem to be studied.

Preliminary Step 3: Purpose Statement

The purpose statement of a study is usually a single sentence that articulates why this study is being conducted, usually to address the research problem. It is generally expected to include the word “purpose,” like, “The purpose of this study is to…” This is the first point in the four preliminary steps of the research process that the researcher actually becomes an active part of things. The previous two steps explain what has been and is; now, the researcher explains how they will help address the problem. The purpose statement may or may not be explicitly stated in a journal article-length manuscript, as it is often implied by the research question(s) or hypothesis(es). However, sometimes it is provided there in lieu of research question(s) or hypothesis(es).

Example Purpose Statement

I phrased the purpose of my dissertation study in this way:

The purpose of this case study was to understand how regulatory compliance generated implicit costs of labor at a SLAC in the Midwest. (Olt, 2018, p. 3)

Preliminary Step 4: Research Question(s) & Hypotheses

Now at the most-specific preliminary step of this process, the topic has been refined to a problem statement, and that problem statement has then been refined to a purpose statement. Now, specific research question(s) or hypthesis(es) are proposed, which are what this study will answer.

Research questions must be carefully worded. Of course, every word of scholarly writing must be precise, but research questions are held to an even higher standard. Differences between wording like using “what” or “why” will not only guide the substance of your research but also your methods/methodology.

Some important characteristics of a research question are that it is clear, precise, and only includes one item to be measured.

- clear. A reader of your research question should come away with no ambiguity about what you are researching. It should be succinct, which is a key component of clarity. Related to the next bullet point here, define any key words in the research question.

- precise. Every word is important. Consider the meaning of every word in the research question and make sure that is exactly what you are wanting to convey. If you are really trying to understand “why” something happens, do not casually use another adverb to introduce your question.

- only includes one item to be measured. Here is a non-example: “How does administrator feedback affect the emotional well-being and teaching performance of first-year teachers?” This is really asking about two different things (well-being and teaching performance), which should be worded as two different research questions, whether done in tandem in one study or explored in two completely different studies.

Make sure to very explicitly define any key terms in your research question. For the words that are the substance of what is being measured, that definition needs to be very narrow and written in a way that it is measurable. For example, consider the following research question: “How do storylines [a pedagogical tool] affect the learning gains of secondary science students?” You would want to define the terms “storylines” (probably immediately adjacent to your research question, as well as in a literature review section that includes a definition as well as the research that has been done this far on the tool), “learning gains” (likely both near your research question and then in the methodology, emphasizing the substance of what is being measured such as pre-/post-tests after a storylined unit as the experimental group), and “secondary science students” (probably briefly near your research question and then thoroughly in your methods section where you describe the participants by demographics including grade level and subject area).

In certain quantitative methods (ex., experimental), it is common to either have (1) both research questions and hypotheses or (2) just hypotheses. An experimental study, for example, would normally have one more hypotheses, though it could also have research questions. In studies where both research questions and hypotheses are present, an hypothesis is normally a statement of the expected findings of the research question, and often a null hypothesis is also stated (and is what will actually be tested). See the simplified illustration below.

- Research Question: Does Intervention A correlate to productivity?

- Hypothesis: Intervention A will positively correlate to productivity.

- Null Hypothesis: There is no correlation between Intervention A and productivity.

How many research questions does my study need?

It is common to wonder how many research questions one needs. The answer to the question is found in the question itself. How many research questions are needed to provide a coherent investigation the generates new knowledge about your topic? You should have exactly that many—no more, no less. Note that this is a subjective answer with no absolute number that is correct or not. For larger, generalizable quantitative studies, it is not uncommon to see anywhere from one to eight research questions. In a qualitative study, one research question is probably most common, but anywhere from one to three is not unexpected. A mixed methods study must have at least three research questions. And finally, action research most commonly only has one research question considered at a time (noting that that process is iterative and thus will consider other questions in later iterations researching the topic).

Example Research Question

The primary/central research question in my dissertation study (which was qualitative) was:

How does regulatory compliance affect labor at a small liberal arts college? (Olt, 2018, p. 4)

Deciding How to Research Your Question(s)/Hypothesis(es)

Once a topic has been refined down to research questions and/or hypotheses, one must decide how they will answer them. The answer on how to research your topic is inside your research question. At the first level, you’ll have to decide upon an over-arching approach to research. For examples:

- If you ask an historical research question, you would use historical methods, though those are humanistic rather than social science (ex., “How did John Dewey’s conception of ‘critical thinking’ affect general education curricula in American higher education from 1900 – Present?”).

- If you ask a research question about what an experience is like, you would likely engage in qualitative research, specifically phenomenology in this example (ex., “What is it like for a member of Gen Z to get their first full-time job after college?”).

- If you asked a research question about the effectiveness of an intervention, you would probably then conduct a quantitative study (ex., “How do storylines [a pedagogical tool] affect the learning gains of secondary science students?”).

- If you asked three or more research questions, wherein at least one is qualitative, one quantitative, and one about the interplay between the two, you would conduct a mixed methods study. (ex., “To what extent does a nursing shortage exist in Iowa? How do members of the Iowa General Assembly perceive their role in addressing the nursing shortage in Iowa? How does funding from the Iowa General Assembly contribute to the nursing shortage in Iowa?”)

The items above are, again, just examples, with many more options for each of the major approaches to social research. However, the “how” should really be derived from “what” exactly you are trying to ascertain. Often, the research questions can only lead to one approach, though that is not absolute.

Getting Approvals

In the United States (and almost every other country), organizations that conduct social science research are required to have an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or equivalent that evaluates the ethical implications of a proposed study. While only organizations receiving federal funding are technically required to have an IRB in the United States, it is a standard matter of practice wherever natural or social science research is conducted. Organizational/institutional IRBs will have different procedures for the application, and so researchers should consult their local IRB for appropriate procedures. Researchers should be aware that they may need multiple IRB approvals if they work at one organization with an IRB but conduct their research at others (or are a graduate student at one institution while working in another organization and researching there).

As part of the IRB approval process, social science researchers will commonly need to include a granting of general permission to conduct research at any sites (ex., a study about College X will need a general permission from an appropriate administrator at College X before proceeding) as well how individual consent/assent will be gained and documented.

Understanding Your Study’s Limitations & Delimitations

One of the most confused aspects of study design, proposal, and write-up is that of limitations/delimitations. It is normal for a study to include a section or sections about limitations/delimitations both in the initial proposal and in the Discussion or Conclusion section of the final write-up.

Limitations are factors that limit your study, usually arising during the study and outside of researcher control. In contrast, delimitations are factors that define the limits of your study, which are inherent to the design and scope of the study.

So, for example, consider the following statement:

In this study, I gathered data in states in the southeastern United States.

That statement is a delimitation. It defines the boundary of your study, in this case geographically. That does not inherently mean the findings would have not applicability in, say, Vermont; however, they would not truly generalize there unless Vermont was included representatively in the population and sample of the study. There could be adequate cultural or structural differences between the southeast and northeast regions that the findings would not be reliable across both. However, delimitations in the final write-up of a journal article-type publication are relatively uncommon compared to the discussion of limitations, as researchers and editors often assume readers will just know delimitations as inherent characteristics of different methods/methodologies. Perhaps that is inadvisable and should be changed—especially in practitioner fields, but it is simply a reality at this point.

Now, consider another statement:

While we had planned to get a profile of survey respondents that mirrored the school population, actual survey respondents were skewed with over-representation among white (race) and female (sex) students. Despite efforts to reach out to students from minority racial groups and males, we were unable to achieve representativeness.

That statement is an example of an actual limitation. Now, like the previous example, the researchers should not feel shame or failure. It is simply a statement of reality. They tried to get a representative population, but that simply did not happen. The researcher cannot ultimately control who participates, especially in a survey sent to an entire school’s population. There could, however, be more added after this statement explaining that this lack of representativeness could skew the results and interpretation.

Key Takeaways

- The most important facet of getting started is to get started. Whatever that means for your specific project—reading other papers, getting word vomit on the page (writing), etc.; make the conscious decision to take the first step.

- From broad-to-specific, your preliminary steps of the research process should proceed as follows: topic → research problem → purpose statement → research question(s) / hypotheses.

Additional Open Resources

Chappell, K., & Voykhanksy, G. (2022). Graduate research in education: Learning the research story through the story of a slow cat. FHSU Digital Press. https://doi.org/10.58809/TUZF3819

Chapter References

Chappell, K., & Voykhanksy, G. (2022). Graduate research in education: Learning the research story through the story of a slow cat. FHSU Digital Press. https://doi.org/10.58809/TUZF3819

Cozby, P. C. (2007). Methods in behavioral research (9th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W. & Guetterman, T. C. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson.

Mills, G. E., & Gay, L. R. (2016). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications (11th ed.). Pearson.

Olt, P. A. (2018). Understanding the implicit costs of regulatory compliance at a small liberal arts college (Publication No. 10812338). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wyoming]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2071826884?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses