To foster an understanding of the diverse practices, products, and services included under the wellness umbrella, along with their sometimes complex underlying assumptions, this chapter explores the maintenance and promotion of physical health through exercise and diet, as well as how wellness aligns with alternative medicine rather than a conventional, biomedical approach. It also highlights historical shifts within the field of psychology and their influence on popular culture, as well as the evolution and integration of spiritual practices in Western society. In doing so, this chapter underscores that while the core dimensions of individual well-being, namely the physical, psychological, and spiritual, have remained unchanged across millennia, the ways in which they are understood and addressed have shifted in response to changing social perceptions and cultural influences.

3 Wellness Modalities and Dimensions of Well-being

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter students will be able to:

- Define and discuss complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) within an historical context, including:

- The impact of the Flexner Report on CAM

- and the differences between nature-based remedies, holistic health and integrative medicine

- Identify dimensions of holistic well-being

- Describe the historical evolution of the dimensions of well-being in the context of social movements such as the New Age, and paying particular attention to the:

- Spiritual

- Psychological

- and Physical dimensions of well-being.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The terms complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) were coined in relation to conventional Western medicine. Holistic approaches to health and well-being are as old as recorded history. The oldest known medical system originates from India, dating back over 5,000 years (Shivanagutti et al., 2022b). This system, called Ayurveda (a Sanskrit term which translates to the study or science of life), was documented in ancient texts that describe health as a dynamic interplay between the body, mind, and spirit, including internal energy systems (the doshas: Vata, Pitta, and Kapha) and external factors such as nature and cosmic forces (Shivanagutti et al., 2022a). It also outlines daily practices designed to maintain internal balance and prevent disease; treatments include lifestyle adjustments, diet, herbal remedies, and other natural therapies (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2024; Shivanagutti et al., 2022a).

In sharp contrast, the historical arc of modern Western medicine swung in favor of a reductionist model focused on identifying localized physical conditions and specific pathologies, and treating them with targeted interventions such as surgery and pharmaceuticals. This model spurred advances in germ theory, biomedical research, and technological innovations but at the expense of more comprehensive approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Through prioritizing a clinical and scientific approach, Western medicine also distinguished itself from nature-based and energetic healing practices, and often marginalized or dismissed traditional knowledge that emphasized prevention, holistic well-being, and the mind-body connection.

In the 1970s, and gaining wider recognition in the 1980s, the label alternative was applied to nature-based, holistic, and traditional systems that operate outside the Western medical paradigm (Peters et al., 2002). After some of these alternative practices were scientifically endorsed or integrated into conventional healthcare (Peters et al., 2002) the term complementary was added, although it is now also used to refer to such systems and practices in their own right (Peters et al., 2002). This shift from alternative to complementary reflects increasing acceptance of such therapies within mainstream healthcare and in recent years, there has been growing interest in so-called integrative medicine (see below) which seeks to blend conventional and alternative approaches. However, the degree of scientific endorsement varies with some practices supported by strong evidence, while others remain controversial. Nonetheless, as CAM aligns with the principles of holistic well-being and preventative care, it is considered integral to the wellness paradigm (Perez et al., 2016).

What comprises complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)?

CAM is a collective term for a diverse range of therapies, each based on a unique understanding of the causes, diagnosis and treatment of disease, especially those derived from health systems such as Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine (see below), which have distinctive historical, cultural and philosophical underpinnings. Examples of CAM therapies include acupuncture, aromatherapy, chiropractic care, herbal medicine, homeopathy, massage therapy, naturopathy, nutritional therapy, reflexology, and reiki (Peters et al., 2002).

The National Institute of Health identified five major categories of complementary therapies as follows:

While CAM therapies and systems of healing vary, many share commonalities. As mentioned, alternative therapies typically embrace a so-called holistic approach that considers an individual’s overall well-being, along with the external factors that impact it (Reiss & Ankeny, 2022). Beginning in the 1970s the term “holistic” became widely applied in the context of health and wellness to capture a whole person perspective, as well as distinguish such an approach from conventional health care which was becoming increasingly high-tech, impersonal, and expensive (Tackett, 1990). For example, a number of alternative therapies such as homeopathy are characterized by comprehensive examinations and extended consultations. During these consultations, practitioners consider the overall integrity of the physical body which may extend to a patient’s emotional, psychological, and spiritual health, along with the unique circumstances of their external environments (Whorton, 2002). While the term holistic health is thus often used to describe alternative health care systems, especially comprehensive ones such as Ayurveda or TCM, it can also refer to an approach to health care that combines different healing modalities such as integrative medicine (Patwardhan et al., 2015).

The term holistic from the Greek word holos, meaning “whole,” was coined by South African statesman, Jan Smuts, in his 1926 book Holism and Evolution. His book highlighted the general problem of specialization in science, resulting in discrete fields of study or ‘silos of knowledge’ that ultimately narrow our understanding of complex phenomena as well as the ability to tackle complex problems.

Another shared principle is a belief in the body’s propensity to heal itself, especially in harmony with nature. Natural remedies using plants, herbs, water, and even climate and sunlight have been used to support the body’s healing processes (Whorton, 2002). Affirmation of the wisdom and potency of nature and natural remedies, along with the idea that health is achieved and maintained in harmony with nature, is likewise prevalent within the wellness movement (Baer, Goldstein, 1992).

Finally, alternative practitioners typically value direct insights gained from patient interactions, such as close observation of physical indicators and attention to changes in overall well-being. Such practitioners have argued that conventional medicine relies too heavily on theoretical deduction and clinical studies, whilst their approach prioritizes the efficacy of a course of treatment as determined through empirical results rather than an understanding of the underlying mechanisms (Whorton, 2002). Conversely, medical practitioners have criticized alternative therapies for their lack of scientific rigor and questionable premises.

Nonetheless, an increasing number of Americans are using CAM, with low estimates around 38% of the adult population (Weerasinghe, 2025). Nearly three-fourths of the U.S. population also feel that conventional healthcare systems are not adequately meeting their needs (Micallef, 2023). Many of them expressed dissatisfaction over the lack of preventative care, and this despite extensive research demonstrating that lifestyle modifications can effectively prevent many chronic ailments such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and even certain cancers (Micallef, 2023). As the World Health Organization projects that 70% of global deaths will be attributable to chronic diseases by 2030, (Al-Maskari, 2010), the demand for preventive care and alternative therapies will also likely increase over time.

Highlight: Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional or classical Chinese medicine (TCM) is a system of medicine that originated in China over 3000 years ago and is still widely practiced throughout Asia (Lee, 2018; (Xu & Yang, 2009). While TCM evolved and adapted over time, a fundamental tenet posits that the same characteristics and forces shaping the cosmos, for example, the Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) and flow of Qi, also operate within the human body; in other words that the macrocosm is reflected in the microcosm or physical body (Lee, 2018).

Qi is described as vital energy, a fundamental and universal life-force that is expressed in all things via two modes: (1) Qi in concentrating mode (matter) refers to the tangible or material aspects of existence, and (2) Qi in dissipating mode (energy) represents a more intangible force that animates matter (Lee, 2018). The Chinese word for Qi combines the characters of “rice” and “steam,” illustrating this duality. Rice symbolizes Qi’s ability to condense and form matter while steam represents its ethereal, flowing nature (Lee, 2018).

In the human body, Qi is the life force that flows through the body’s intricate meridian system, a network of pathways called Jingluo (Lee, 2018). The Jingluo network also serves as the transportation system for blood, ensuring the proper functioning of the visceral organ-systems (Lee, 2018). Blockages or imbalances in Qi are believed to be the root of illness while maintaining the smooth flow of Qi is essential to good health. Thus, supporting the integrity of these meridians plays a critical role in TCM therapies (Lee, 2018).

Natural phenomena and their relationships are categorized into The Five Elements, a framework that extends to an understanding of the body’s physical functions as well as an individual’s temperament, personality traits, and even destiny in some interpretations, such as in Chinese metaphysics and astrology. The season spring, for example, corresponds to the wood element, the liver (considered yin) and its catalyst the gallbladder (considered yang), as spring symbolizes growth and renewal, much like the liver’s detoxifying and regenerative role (Lee, 2018). TCM practitioners apply the Five Element framework to interpret symptoms and diagnose imbalances. By identifying which element is out of balance, they may prescribe treatments that restore internal harmony as well as balance between the individual and the external world.

TCM also favors a holistic and preventative approach to health and healing. Practitioners view the human body as a complex, interconnected system in which the emotional, mental and physical spheres must work in harmony to maintain balance and individual vitality (Lee, 2018). Emotional imbalances such as suppressed anger or excessive emotions can disrupt the flow of Qi and if left unresolved, become significant contributors to physical disease (Lee, 2018). TCM practitioners use a variety of methods to assess the flow of Qi and the integrity of vital organs in the body (Lee, 2018). They may observe the tongue and complexion, how the body sounds and smells, feel the pulse and ask questions about lifestyle and symptoms, to better understand a patient’s condition (Lee, 2018). They also anticipate potential health challenges and recommend lifestyle and dietary adjustments as early intervention and preventative measures are key (Lee, 2018).

Chinese medicine is time therapy, based in the ancient science of energy dynamics, while Western medicine is space therapy, rooted in the modern science of matter analysis. (Fruehauf, 2006)Popular TCM treatments include acupuncture which stimulates acupoints on the body to release energy blockages and re-establish the body’s equilibrium and natural remedies such as medicinal plants, minerals and, now more controversially, animal parts to treat patients (Lee, 2018). Other modalities include nutrition and movement exercises like Qi Gong and Tai Chi (Lee, 2018).

Today, TCM remains widely practiced in many parts of Asia, with 90% of general hospitals in China having TCM departments (Xu & Yang, 2009). Among the nearly 4,000 international students enrolled in TCM universities, 90% come from Asian countries, 5% from North America, and 4% from Europe (Xu & Yang, 2009). Many Chinese people also continue to favor traditional practices (Xu & Yang, 2009). While Western medicine is accepted alongside TCM, debates persist on how to effectively integrate these vastly different systems (Xu & Yang, 2009).

From nature based remedies to integrative medicine – a brief historical overview

The use of nature-based remedies has historical roots in ancient civilizations worldwide, with each culture developing unique methods of healing using the natural resources at hand (Ng et al., 2023; Whorton, 2002). The early European settlers brought knowledge of such practices and remedies with them from their respective countries (Whorton, 2002). Native Americans likewise relied upon indigenous plants for healing, knowledge of which was incorporated by early colonialists (Craker & Gardiner, 2006). Historically, close plantings of medicinal plant materials were placed near homes for easy use in treating ailments, a practice commonplace in America until the early 20th century. (Silvano, 2021). Up until the late 19th century, medical training for herbalists, midwives, and physicians also included the knowledge and use of plant-based medicines (Craker & Gardiner, 2006).

In a Western context, formal systems of nature-based cures began to develop around the late 1700s (Whorton, 2002). One nature-based system of healing which originated around that time is Homeopathy, founded by Samuel Hahnemann, a German physician (Ng et al, 2023). Homeopathy is based on the “law of similars,” the principle that a substance that causes symptoms in a healthy person can cure similar symptoms in a sick person, using highly diluted preparations (Ng et al., 2023). Another such system that became popular in the early 1800s was developed by Samuel Thomson (Whorton, 2002). Called Thomsonianism, this system drew upon folk traditions and extensive experimentation with plants and herbs (e.g. lobelia and cayenne) that Thomson used to create botanical remedies (Whorton, 2002). Vincent Priessnitz’s water cure, which inspired hydropathy, also originated in the early 19th century and was based on his observations of the healing properties of water (Whorton, 2002).

Nature-based remedies enjoyed wide spread popularity during the first half of the 19th century (Whorton, 2002). This was in large part a reaction to the “heroic therapies” prevalent within conventional medicine at the time (Whorton, 2002). Allopathic therapies of the early 1800s, for example, included such practices as non-anesthetized surgeries, leeching and blood-letting, and foul-tasting substances that sometimes induced horrific side effects (Whorton, 2002). A particular mercury compound, widely prescribed as a cathartic, even caused painful mouth swelling, bleeding gums, ulceration, loose teeth, and excessive salivation (Whorton, 2002). Such dubious treatments were at best unreliable and quite often harmful, if not life threatening (Whorton, 2002).

Nature-based remedies that supported the body’s natural ability to heal were gentler and more palatable, contributing to the popularity of the doctors who prescribed them. This is evidenced by the fact that approximately 20% of all recorded health practitioners in the 19th century were not conventionally trained physicians (Whorton, 2002). As the century drew to a close, practitioners such as herbalists, massage therapists, hydropaths, and homeopaths enjoyed thriving health practices alongside a growing number of adherents (Tackett, 1990). However, allopathic physicians, for whom such practitioners were professional competition, dismissed them as “quacks” and labeled treatments based on the restorative power of nature as Romanticized ideals (Tackett, 1990). More damaging, however, was the unscrupulous profiteering off the rising popularity of natural remedies, which led to a variety of questionable “cure-alls” being hawked by traveling salesmen (Whorton, 2002). This development ultimately injected a heavy dose of skepticism into public perception, undermining the credibility of natural and nature-based remedies (Tackett, 1990).

The increasing dominance of conventional medicine over the following century was driven by the publication of the so-called Flexner Report (see below), along with scientific medical discoveries, advances in pharmacology, and a good deal of political lobbying (Tackett, 1990). By the end of the 20th century, synthetic drugs had also all but replaced natural and plant-based remedies within conventional medicine. In 1916, 40% of medicinal preparations came from plant extracts; by 1950, this dropped to 9%, and by 1990, only 1% of preparations were derived from plants (Craker & Lange, 2006).

ASPIRIN

Aspirin, also known by acetylsalicylic acid the active ingredient, is one of the most ubiquitous drugs in the world and its use dates back thousands of years. Aspirin originally comes from the bark of the willow tree which contains salicylic acid, the compound responsible for pain relief. The Sumerians and Egyptians used willow bark as a painkiller and fever reducer (Montinari, 2019). Likewise, Native Americans chewed willow bark to relieve aches and pain. British Reverend Edward Stone brought willow bark’s therapeutic effects to a wider audience in 1763, but it wasn’t until 1897 that chemists began artificially synthesizing acetylsalicylic acid; the Bayer company trademarked the name “Aspirin” a year later (Montinari, 2019).

Aspirin, also known by acetylsalicylic acid the active ingredient, is one of the most ubiquitous drugs in the world and its use dates back thousands of years. Aspirin originally comes from the bark of the willow tree which contains salicylic acid, the compound responsible for pain relief. The Sumerians and Egyptians used willow bark as a painkiller and fever reducer (Montinari, 2019). Likewise, Native Americans chewed willow bark to relieve aches and pain. British Reverend Edward Stone brought willow bark’s therapeutic effects to a wider audience in 1763, but it wasn’t until 1897 that chemists began artificially synthesizing acetylsalicylic acid; the Bayer company trademarked the name “Aspirin” a year later (Montinari, 2019).

The Flexner Report

Formally known as The Carnegie Foundation Bulletin Number Four, the so-called Flexner Report was published in 1910, having been commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to evaluate and reform medical education in North America (Duffy, 2011). The report led to standardized curricula with a sharp focus on research, significantly professionalizing the field of medicine (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). Educational reforms included raising medical school admission standards and lengthening medical education (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). The proposed integration of medical schools into larger research universities further ensured both clinical research and scientific rigor in education, as well as an academically oriented model of patient care, but at the expense of more holistic and patient-centered approaches (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012).

The Flexner Report had a profound and lasting impact on the medical landscape of North America (Duffy, 2011). Abraham Flexner, the report’s author, favored a biomedical model and considered alternative and nature-based cures unscientific, entrenching the divide between conventional and alternative medicine (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). The report also recommended that only physicians trained in approved institutions should be allowed to prescribe treatments, consolidating power within a narrowly defined medical model (Duffy, 2011). These recommendations also led to the closure of many institutions, including CAM-oriented and homeopathic colleges, predominantly African American institutions, and even some psychiatric facilities (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). The publication of the report coincided with an industrializing America and the rise of chemically-based medicine, which further sidelined plant-based remedies (Craker & Lange, 2006). Within a few years, most schools teaching botanical medicine had also closed (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012).

While Flexner’s report brought about important reforms in medical education, its assessment of alternative medical practices had a detrimental impact on their use and development. The exclusion of CAM from standardized curricula institutionalized skepticism toward such practices and eroded the perceived legitimacy and overall popularity of non-traditional medical treatments and therapies in both mainstream healthcare and the general populace (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012).

Integrative medicine

In the late 1960’s the prevailing medical model remained almost exclusively surgical and pharmacological in focus (Tackett, 1990). During this period, however, wellness advocates began calling for a more comprehensive approach that went beyond eliminating symptoms to health maintenance and disease prevention (Tackett, 1990). The 1960s also saw increasing support for unconventional medical practices and more holistic, human-centered care (Ng et al., 2023).

Ground support grew during 1970s to the point that the medical world was rocked by a “holistic health explosion” (Whorton, 2002). A unifying contention was that modern medicine was guilty of a “presumptuous expertise” which forced every form of human suffering into its narrow biomechanical construct of disease (Whorton, 2002). The word holistic, having been introduced to medicine in the 1970s, initially referred to the treatment of the whole person (Whorton, 2002). Alternative therapy practitioners embraced the word as an ideal that distinguished them from conventional medicine, expanding its meaning to include the use of natural therapies, preventive measures, and patient education (Whorton, 2002).

Patient demand for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) also continued to grow throughout the1980s, with more doctors becoming interested by the end of the decade (Whorton, 2002). A 1990 survey found that 34% of adults had used at least one complementary therapy in the past year, a prevalence that had increased to 42.1%, by 1997, although interestingly less than 40% of CAM therapy reported disclosing this to their physicians in both the 1990 and 1997 survey (Institute of Medicine, 2005). By 2002, the number of U.S. adults who had used some form of CAM in the past 12 months had risen to 62% (Institute of Medicine, 2005).

While skepticism towards CAM in mainstream healthcare persisted, expansion of so-called integrative medicine began to signal a movement towards endorsement of particular therapies. In 1991, the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) was founded, becoming the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) before being renamed, yet again, as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) in 2014 (Ng et al, 2023). Integrative health, as defined by the NCCIH, brings together conventional and complementary approaches emphasizing multi-modal interventions and holistic treatments involving coordinated care among different providers and institutions (Ng et al., 2023).

By the new millennia, medical and psychiatric education had also begun to change, with trends in certain CAM and evidence-based medicine (EBM) becoming part of the medical school curricula (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). In 2000, integrative medicine took a further step forward with the launch of the American Board of Integrative Holistic Medicine (ABIHM) and introduction of an inaugural board certification examination (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012). In 2014, the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine (AIHM) was founded, which coincided with the launch of yet another board certification, this time through the American Board of Physician Specialists (ABPS) (Ng et al., 2023). While ABPS pointedly refutes the idea that integrative medicine should be considered synonymous with complementary or alternative medicine, they acknowledge that integrative medicine was influenced, in part, by CAM practitioners and may include practices labeled as alternative (Ng et al., 2023).

Dimensions of Well-being

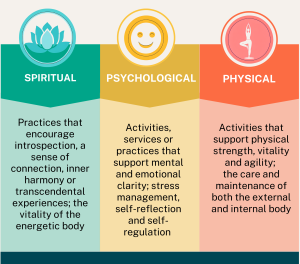

Holistic health is a conceptually complex and multi-faceted term as we witnessed in the wellness models touched upon in Chapter 1. For the purposes of this course, however, we will focus on three fundamental and individual dimensions that have direct relevance for wellness tourism. That is, external circumstances of an individual’s daily life and environment (e.g. work, leisure, family etc.) that are not part of the tourism experience, are necessarily excluded. These three dimensions also comprise the wellness services and amenities that are typically catered to through the wellness tourism industry as we will discuss in Chapter 6: Wellness Tourism Management.

These three are the (1) spiritual, (2) psychological, and (3) physical dimensions of well-being depicted in Figure 5, below. Note that while these dimensions are described separately it is important to keep in mind that they are inextricably linked with each having, “a potentially causal impact on the other” (Goldstein, 1992, p. 25). In practice they are likewise intertwined as exemplified by wellness gurus like Dr. Joe Dispenza who lectures extensively on personal transformation through meditation and spiritual principles, thus harnessing the power of thoughts and beliefs to bring about physical and psychological healing.

Figure 5: Dimensions of Well-being

Many spiritual facets of the contemporary wellness movement are derived from the New Age movement of the 20th century. Concepts prevalent in wellness communities today, such as energy healing, visualization, affirmations, and manifestation, were fostered under the New Age banner (Baer, 2003; Hanegraaff, 2000; Urban, 2015). Conversely, by the end of the 20th century, the term New Age had become a catch-all for a wide array of esoteric practices, such as Tarot, crystal and sound healing (Chryssides, 2007), many of which are now included under the banner of modern spirituality (Levin, 2024).

Although broad in scope, central tenets of the New Age movement included belief in a transcendent ‘self’ and the idea of engaging the divine within (Houtman & Aupers, 2007). This spiritual orientation was introduced by the Theosophical Society and New Thought, organizations that predated the New Age movement and played significant roles in promoting diverse spiritual paths alongside broader themes of self-discovery and enlightenment (Dresser, 1919; Hanegraaff, 2000; Tumber, 2002). Established in the late 19th century, these organizations’ teachings were controversial for their time, challenging both mainstream religion and scientific materialism by advancing metaphysical ideas outside dominant paradigms. However, the stage for their dissemination was set by Spiritualism, a mid-1800s movement that popularized spirit communication, personal spiritual experience, and an expanded view of human consciousness (Tumber, 2002; Wessinger et al., 2006).

Religion versus Spirituality

While there is no single, agreed upon academic definition for the term religion, from a sociological perspective religion may be described as organized, institutionalized systems of beliefs and practices shared by a community and often marked by formal structures, doctrines, and rituals. By contrast, spirituality is typically individualistic, emphasizing personal experiences, beliefs and practices that are flexible, informal, and open to blending elements from various spiritual traditions, and even creating entirely new expressions (Hjelm, 2021). Note that in the first instance, the sources of inspiration and authority are institutional or external while in the second they are personal or internal.

Spiritualism

Spiritualism was founded on the belief that individuals could communicate with the deceased through mediumship. The movement began in 1848 in western New York after two teenage girls, known as the Fox sisters, began to communicate with the spirit of a man buried in their cottage basement (Tumber, 2002; Wessinger et al., 2006). When esteemed community members acknowledged the sisters’ ability to connect with the beyond, the phenomena became widespread as many more “mediums” emerged, claiming the ability to speak to those in the afterlife (Tumber, 2002).

Spiritualism was especially appealing as mortality rates were high and traditional beliefs offered small comfort to those grieving the loss of loved ones, particularly parents afflicted by the death of children which was a common occurrence at the time (Masarik, 2025). In practice, Spiritualism took many forms such as séances, table tipping, and trance work but as the movement swelled, many such practices began to face skepticism, particularly after a number of frauds and hoaxes were exposed (Bowlin, 2019). While the movement ultimately fell out of favor, its enduring contributions were popularizing the concept of a spirit realm beyond material reality, and fostering an environment in which challenging conventional sources of spiritual and scientific authority was at the very least, permissible (Dresser, 1919; Tumber, 2002). Spiritualism thus provided fertile ground for the emergence of Theosophy and New Thought, both of which propagated openness to alternative spiritual frameworks, esoteric knowledge, and mind-over-matter philosophies (Dresser, 1919; Tumber, 2002; ).

The Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society was founded in New York City in 1875 by Russian aristocrat Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and her partner Henry Steel Olcott (Wessinger et al., 2006). Blavatsky disseminated her ideas through writings and lectures, becoming an internationally renowned, albeit controversial figure (Bergunder, 2014). Unconventional and charismatic, she has been credited with the rapid growth of the Theosophical Society, which attracted thousands of members along with many more admirers worldwide by the time of her death in 1891 (Tumber, 2002).

The Society itself was initially rooted in Western mysticism which encompassed a blend of Egyptian and Greek esoteric teachings (Hanegraaff, 2000; Wessinger et al., 2006). Early members believed in a universal kabbalah and delved into divinely inspired magic, unexplained laws of nature, and latent human potential (Hanegraaff, 2000). In 1882, the Society relocated its headquarters to India, however, where it began to integrate Eastern traditions, particularly Buddhism and Hinduism, into a unique blend of Eastern and Western spiritual thought (Hammer & Rothstein, 2013; Hanegraaff, 2000; Tumber, 2002). Blavatsky’s later writings, for example, synthesized Eastern and Western spiritual traditions, describing an overarching ‘Ancient Wisdom’ that Theosophists had come to believe formed the esoteric core of all religions (Tumber, 2002).

In Blavatsky’s second major work, The Secret Doctrine (1888), she expanded on this broadened theoretical base by articulating a cosmology that included a hierarchy of ‘Masters of the Wisdom,’ or enlightened beings, who guided the evolution of Earth and human development (Tumber, 2002). In this voluminous work, Blavatsky described an impersonal, eternal, and boundless principle (the Absolute), from which all existence emanated (Tumber, 2002). Planes of existence, populated by hierarchical entities such as cosmic beings, elementals, and disembodied souls (Wessinger et al., 2006), formed a cosmology involving cycles of cosmic evolution, known as the Sevenfold Division (Wessinger et al., 2006). She also claimed to communicate psychically with the Masters of the Wisdom, the primary source of her teachings, which would spawn forms of spirituality later embraced by the New Age movement (Chryssides, 2007; Wessinger et al., 2006). Blavatsky’s books, for example, popularized Eastern spiritual concepts such as reincarnation, karma, and chakras, which have since become pervasive in Western thought. She also significantly impacted the incorporation of concepts like auras and subtle energies into the lexicon of alternative spirituality (Levin, 2022; Wessinger et al., 2006). The Theosophical Society still exists in an abridged form today, with a legacy that includes the idea of a ‘Universal Brotherhood of Humanity’ and aspirations for a period of global peace and justice following the dawning of a new era or cycle of spiritual enlightenment (Wessinger et al., 2006).

New Thought

New Thought emerged out of Midwestern urban centers in the late 19th century (Wessinger et al., 2006). Its ideological foundations are largely credited to Emma Curtis Hopkins, who formalized its principles and became known as the “teacher of teachers” (Wessinger et al., 2006). Another key figure was Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, a mental healer, who, in turn, was influenced by spiritual leaders such as Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Church of Christian Science (Wessinger et al., 2006). New Thought itself had no formal structure, however, rejecting rigid institutions and religious dogma in favor of recognizing the inherent divinity of each individual, or ‘Christ within’ (Dresser, 1919).

New Thought aligned with the growing interest in concepts like karma and reincarnation, which were being propagated by the Theosophical Society at the time (Dresser, 1919). However, New Thought distinguished itself by focusing on practical, experience-based approaches rather than complex metaphysical systems (Wessinger et al., 2006). Key principles included the belief that mental states influenced material reality and that altering one’s thinking could positively impact both internal states and external circumstances (Dresser, 1919).

Practices such as affirmations, positive thinking, and visualization thus became central (Dresser, 1919; Wessinger et al., 2006) as New Thought asserted that people could transform their own lives by cultivating a mindset that aligned with spiritual and universal principles. Such an emphasis on autonomy and self-reliance also reflected a broader reaction against conventional, authoritarian systems and in favor of autonomy and self-reliance (Dresser, 1919; Wessinger et al., 2006). New Thought’s long-term popularity has thus been attributed, in part, to its resonance with American ideals of individual freedom and the pursuit of personal happiness (Dresser, 1919).

New Thought principles regarding personal transformation, individual empowerment, manifestation, and the power of the mind also served as precursors to the New Age movement (Levin, 2022) and, by extension, the wellness movement. Concepts like positive thinking, visualization, and affirmations, for example, would later become integral to self-help books such as Rhonda Byrne’s New York Times bestseller The Secret (2006) or personal development groups such as those run by wellness guru, Joe Dispenza.

Today, New Thought spiritual centers still exist worldwide through organizations like Unity Church, Centers for Spiritual Living, and the Church of Divine Science. While some of these groups remain traditional, many contemporary New Thought practitioners have expanded core teachings to include more diverse practices and spiritual routines.

The New Age Movement

The New Age movement, which became widespread in the 1960s and gained increasing popularity throughout the 1970s and 1980s, consisted of a diverse network of practitioners who embraced alternative spiritual beliefs and practices (Kraemer, 2013). Drawing on earlier esoteric and metaphysical teachings, particularly those of Theosophy and New Thought, the movement was characterized by eclecticism and individualism rather than a cohesive set of principles (Kraemer, 2013; Wessinger et al., 2006). In fact, the term “New Age” is more accurately understood as a label applied by external observers to a variety of beliefs and practices that both mirrored and contributed to a broader cultural shift toward individualism, self-development, spiritual exploration, and holistic living (Hanegraaff, 2000; Kraemer, 2013; Wessinger et al., 2006).

New Age practitioners were not only diverse but also decentralized as the movement reflected an egalitarian approach to spirituality that recognized the inherent potential and divinity of each individual (Mears & Ellison, 2000; Wessinger et al., 2006). Like its predecessors, New Age spirituality drew from a blend of alternative traditions and systems of belief, combining religious teachings from Hinduism and Buddhism with Western mysticism, neopaganism, neoshamanism, self-actualization practices, and individual inspiration (Baer, 2004; Levin, 2022; Wessinger et al., 2006). Spiritual teachings themselves were often advanced by occasional luminaries based on individual inspiration rather than through a hierarchical framework or unifying creed (Chryssides, 2007). Alice A. Bailey is a case in point. Bailey was initially a member of the Theosophical Society, contributing to its impact on alternative spirituality and spreading its beliefs. Bailey’s views began to diverge significantly from certain aspects of Theosophy, however, leading her to break away with the aim of spreading her own spiritual teachings (Wessinger et al., 2006).

In 1923, Bailey established the Arcane School in New York and began to outline a neo-theosophical platform which covered topics like psychology, cosmology, and esoteric healing. Bailey, who was reportedly in communication with ascended Masters, introduced concepts like spiritual evolution and the transformation of human consciousness in her writings, as well as promoted the belief that the physical body is influenced by spiritual forces and subtle energies beyond material reality (Melton, 2024). One of her most notable contributions, however, was coining the term “New Age” to signify the arrival of a new astrological era (Baer, 2004). The Arcane School also initiated a program called “Triangles,” in which groups of three individuals meditated to transmit divine energy, helping to facilitate the imminent arrival of the Aquarian Age (Melton, 2024).

By the 1960s, momentum had shifted from formal, membership-based organizations like the Theosophical Society and New Thought to a decentralized, non-institutionalized network of individuals with similar practices and belief. Strongly linked to the counterculture, the New Age movement attracted mainly younger generations rejecting mainstream Western dogma in favor of alternative spiritual experiences, self-transformation, and a holistic worldview that emphasized universal harmony, a deep connection to nature, and optimism about humanity’s future (Kraemer, 2013; Wessinger et al., 2006). Earlier movements nonetheless continued to influence New Age adherents through established literature, while growing interest in Eastern spirituality was often pursued through self-study (Wessinger et al., 2006). Alternative spirituality centers, such as the Esalen Institute, also emerged as hubs for exploring these ideas, further fueling expansion of the New Age (Wessinger et al., 2006).

By the 1970s, the term “New Age” had entered the mainstream lexicon (Levin, 2022). Emergent figures like Jane Roberts began to exert significant influence through published messages, underscoring the enduring power of individual inspiration to shape New Age ideas (Mears & Ellison, 2000). Her book entitled The Seth Material (1970), was highly influential and introduced channeling to a wider audience and as well as helped shape many of the core New Age beliefs of the time (Mears & Ellison, 2000). As a wider audience began to engage with New Age ideas through reading books, listening to audiotapes, and watching videotapes the movement’s growing momentum also began to foster informal gatherings and topical workshops, allowing individuals to explore and share their personal experiences and spiritual perspectives (Mears & Ellison, 2000).

The 1980s marked a key phase in the New Age movement’s evolution as it became further embedded in popular culture and increasingly commercialized (Wessinger et al., 2006). Books continued to play a pivotal role, with Marilyn Ferguson’s The Aquarian Conspiracy (1980) introducing key concepts like individual transformation and societal change (Baer, 2004). This was followed by Shirley MacLaine’s Out on a Limb (1983), which had an even greater impact on mainstreaming New Age ideas. MacLaine’s autobiographical account of self-discovery, reincarnation, meditation, and mediumship became a New York Times bestseller and was later adapted into a successful miniseries in 1987.

During this decade, more people sought guidance from psychics, shamans, and healers specializing in aura cleansing and past-life regression than ever before, while specialty shops selling tarot cards, crystals, incense, and alternative remedies proliferated (Wessinger et al., 2006). New Age bookstores offered texts on topics ranging from ley lines and the paranormal to astrology and esoteric spirituality (Chryssides, 2007; Wessinger et al., 2006). As a result, and as the movement extended beyond early spiritual seekers, critics condemned what they saw as a covert takeover of spirituality by the forces of capitalism (Chryssides, 2007; Wessinger et al., 2006). Expos and “metaphysical department stores” further fueled the movement’s commodification, turning it into what some called a “spiritual supermarket” where consumers could pick and choose elements and tokens of spirituality that most appealed to them (Woodhead & Kawanami, 2003).

By the 1990s, the term New Age began to lose favor, even as its principles and practices had become deeply embedded in contemporary culture (Levin, 2022). Many drawn to alternative spirituality distanced themselves from the label, seeing it as burdened with unwanted associations. Yet rather than fading, the movement was shifting from its counter-cultural roots to a cultural mainstay, including in areas such as religion and medicine. The immense success of The Celestine Prophecy (1995)—the world’s bestselling novel for two consecutive years and a New York Times bestseller for over three years, highlighted the extent to which New Age ideas had expanded beyond a niche subculture to resonate with a much broader audience (Hanegraaff, 2000). Today, New Age ideas also persist within the “spiritual-but-not-religious” category, with which over 30% of Americans identify (Petrzela, 2020). Additionally, over a million Americans now practice alternative traditions such as Wicca, neo-paganism, and folk magic which comprise the fastest-growing spiritual movements in the U.S. (Pagliarulo, 2022).

New Age thought also continues to shape the modern wellness movement, integrating alternative practices and holistic therapies into the mainstream (Levin, 2022). Practices like crystal healing, sound baths, and aura cleansing are widely accepted within the wellness industry and tourism sector (Rice & Cheresson, 2020; Sutcliffe, 2009). The term New Age, which was once used interchangeably with alternative healing practices, and the movement at large also played a key role in popularizing nature-based remedies and integrative healing practices (Levin, 2022).

Science and spirituality

Many within the New Age and alternative spirituality movements have drawn inspiration from concepts in scientific frameworks such as Chaos Theory and, more recently, the mind-bending realms of Quantum Physics, both of which, in turn, have helped shape the movement’s spiritual and intellectual tenor (Baer, 2004; Wessinger et al., 2006). Chaos Theory suggests that seemingly random systems have underlying patterns, which some New Age thinkers relate to concepts like synchronicity or divine order. Quantum Physics, particularly concepts such as quantum entanglement and the observer effect, has been used—albeit controversially—to support beliefs in consciousness affecting reality, interconnectedness, and non-material dimensions of existence.

Mainstream scientists, however, often criticize these interpretations as oversimplifications or misapplications of complex scientific principles. While the broader scientific community remains skeptical of any overlap, parallels between principles in Eastern philosophies and Quantum Physics have been drawn since the field’s inception. Pioneers in Quantum Mechanics, such as Erwin Schrödinger—famously known for his thought experiment involving a paradoxical cat—were drawn to Eastern mysticism. Fritjof Capra later played a key role in popularizing these ideas with The Tao of Physics (1975), a groundbreaking book that framed Quantum Physics and Eastern mysticism as overlapping in their understanding of the universe. Similarly, David Bohm, an influential theoretical physicist, explored the philosophical dimensions of quantum mechanics in Wholeness and the Implicate Order (1980), coining the term “implicate order” to describe undivided wholeness, a concept resonating with Eastern ideas of cosmic unity. Additionally, Gary Zukav’s The Dancing Wu Li Masters (1979) and Deepak Chopra’s works, such as The Spontaneous Fulfillment of Desire (2003), have explored similar themes, interpreting quantum physics in spiritual terms and helping to popularize these ideas within the New Age movement.

Psychological well-being

Within the social sciences, the contemporary wellness movement is most closely aligned with the field of Positive Psychology. Positive Psychology comprises the scientific study of the positive aspects of human life, such as well-being, happiness, strengths, and thriving at individual, community, and institutional levels and thus represents a significant departure from psychology’s traditional focus on mental disorders (Kim et al., 2012). It did not, however, emerge from the abyss but was influenced by earlier developments most notably in Humanistic Psychology. We will briefly touch upon the field of psychology leading up to and including the founding of Positive Psychology. We will also consider how, in tandem with the New Age movement, ideas associated with Humanistic Psychology were disseminated in popular culture through the Human Potential Movement.

What is psychological well-being?

While there is no single, agreed upon academic definition for the term religion, from a sociological perspective religion may be described as organized, institutionalized systems of beliefs and practices that are shared by a community and often marked by formal structures, doctrines, and rituals. In contrast, spirituality may be described as individualistic, emphasizing personal experiences, beliefs and practices that are flexible, informal, and open to blending elements from various religious practices or spiritual traditions, or creating entirely new expressions (Hjelm, 2021). Note that in the first instance, the sources of inspiration and authority are institutional or external while in the second they are personal or internal.

The Field of Psychology

Ancient Greek and Roman civilizations attributed mental illness to internal imbalances while during the Middle Ages, it was often seen as a result of sin, demonic possession, or divine punishment (Jutras, 2017). Asylums as specialized mental institutions began to emerge in the 16th century, particularly during the Renaissance period, where individuals deemed mentally ill were confined for treatment (Jutras, 2017).

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that psychology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline. Around that time, Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud introduced psychoanalysis which marked a significant shift in the understanding and treatment of mental health (Jutras, 2017). Psychoanalysis proposed a therapeutic method that focused on exploring the unconscious mind and its impact on behavior, aiming to bring repressed memories and inner conflicts to conscious awareness(Jones & Wessely, 2007).

Just after the turn of the 20th century, American psychologist John B. Watson advanced Behaviorism, arguing that psychopathology stemmed not from unconscious processes but from external conditioning. Asserting that environmental reinforcements and punishments were the primary determinants of behavior, Watson’s approach, influenced by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, emphasized reconditioning to modify behaviors (Jutras, 2017).

Humanistic Psychology was established in the 1940s and gained traction in the 1950s as a “third force” in response to the deterministic and reductionist theories of these prevailing psychological schools (Waterman, 2013). In contrast to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, Humanistic Psychology embraced a holistic view of the human experience centered upon personal agency, free will, and the importance of subjective experience in shaping behaviors (Aanstoos, 2003).

The movement, led by figures such as Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Rollo May, and Charlotte Bühler, also emphasized an individual’s potential for leading a fulfilling life through personal growth and development. Its origins can be traced to Maslow’s 1943 article A Theory of Human Motivation in which he introduced his Hierarchy of Needs that culminates in self-actualization, a stage Maslow described as the fulfillment of one’s true potential through creativity, authenticity, and purpose (Aanstoos, 2003; Bühler, 1971).

Carl Rogers later pioneered client-centered therapy, shifting the focus from therapist-driven interpretations of a patient’s condition to client empowerment (Waterman, 2013). Rollo May incorporated existential philosophy, emphasizing humanity’s search for meaning, while Charlotte Bühler’s lifespan research highlighted the pursuit of self-actualization as a lifelong process (Taylor, 2001).

Over the latter part of the 20th century, other new approaches and schools of thought emerged in the treatment of mental health. The 1950s saw the rise of a pharmacological perspective in psychiatry, with emerging theories about the biochemical basis of depression and affective disorders treatable with medications (Jutras, 2017). In the 1960s, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) emerged, integrating insights from Aaron T. Beck—who focused on identifying and altering negative thought patterns—with those of Albert Ellis, who emphasized the role of irrational beliefs in mental distress (Jutras, 2017).

While the field of psychology continued to diversify during the latter half of the 20th century, it was Humanistic Psychology that paved the way for the emergence of Positive Psychology by shifting the focus from pathology and dysfunction towards the study of human potential and well-being (Kim et al., 2012). It is worth noting, however, that the founders of Positive Psychology have acknowledged Humanistic Psychology as only one of several progenitors, though not the most significant (Waterman, 2013). Positive Psychology, for example, included the concept flourishing, an optimal state of human functioning rooted in the Aristotelian idea eudaimonia, which defines well-being as the cultivation of a virtuous life aligned with one’s true nature (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Waterman, 2013). In addition, while both disciplines shared a holistic approach focus on well-being, in practice they diverged in key ways. Whereas Humanistic Psychology emphasized subjective experience and personal meaning-making, Positive Psychology prioritized empirical research, including the study of strengths, virtues, and objective well-being (Waterman, 2013).

Nonetheless, Humanistic Psychology is widely recognized for its contributions not only to Positive Psychology but also to the broader field of psychology and beyond. By shifting focus toward the positive aspects of human experience, it laid the conceptual groundwork for investigations into self-development and self-fulfillment that subsequently spread to allied fields such as management and education, as well as gained worldwide attention through so-called ‘pop psychology’ (Aanstoos, 2003; Frey, 2011; Kim et al., 2012)

Carl Jung

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and former disciple of Freud, was the founder of analytical psychology. Jung expanded research on the subconscious mind to include the collective unconscious which he described as a universal storehouse of archetypes and symbols shared by all humanity (Derfer et al., 2013). He identified a number of archetypes (e.g., the hero, and the maiden, mother, and wise crone) which he described as primordial patterns of thoughts and behaviors which are expressed in dreams, myths, and religious symbols. Jung also discussed the workings of the shadow—the unconscious aspect of the personality that the conscious mind represses, and which often contains those primitive instincts and behaviors deemed unacceptable by society (Boree, 2006). Jung believed that integrating the shadow was an essential part of the individuation process, a process which involves reconciling such repressed and unconscious forces to achieve wholeness and self-realization (Boree, 2006).

While his theories were not considered part of Humanistic Psychology, Jung’s work significantly influenced the field along with broader psychological and spiritual discourses. In line with Humanistic Psychology, a number of his theories have been used to understand the self and promote personal growth. Many of Jung’s ideas, such as the collective unconscious and the integration of the shadow, were also widely embraced in New Age circles, and have influenced various practices, including spiritual healing, the use of astrology in psychological analysis, and depth psychology that includes the workings of the unconscious mind. Jung is also known for coining the term synchronicity to describe the occurrence of two events that are not causally or teleologically linked but are meaningfully related (Boree, 2006).

The formal launch of Positive Psychology is credited to Martin Seligman’s 1998 Presidential address to the American Psychological Association, entitled Building Human Strengths: Psychology’s Forgotten Mission (Kim et al., 2012). In his speech, Seligman urged a shift in focus from mental damage and psychological pathology to nurturing human strengths and virtues (Kim et al., 2012). Two years later, the journal American Psychologist published a special issue dedicated to the emerging field of Positive Psychology, thereby bringing it to the attention of a much wider audience. In the introduction of that January issue, Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described the field of Postive Psychology as encompassing the study of, “well-being, contentment, and satisfaction (in the past); hope and optimism (for the future); and flow and happiness (in the present)…..(along with) positive individual traits: the capacity for love and vocation, courage, interpersonal skill, aesthetic sensibility, perseverance, forgiveness, originality, future mindedness, spirituality, high talent, and wisdom” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5).

Since its founding, this field has had a significant impact on psychological research and has come to encompass several related areas of study such as Self-Determination Theory, which now falls under the Positive Psychology umbrella.

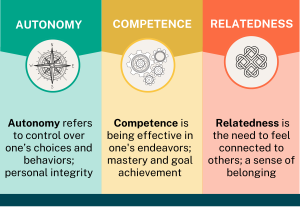

Highlight: Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a macro* theory of human motivation that examines the impact of need satisfaction and motivation on engagement, performance, and psychological well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2024). Likewise rooted in Humanistic Psychology, SDT falls under the umbrella of Positive Psychology as well as resonates with the overarching principles and aims of the wellness movement. In development since the 1970s, SDT has consistently shown strong empirical support for its core principles (Vansteenkiste, Niemiec, & Soenens, 2010). Over the last few decades, a vast body of research with broad application across diverse fields such as education, healthcare, work, sports, and psychotherapy, thus helped establish SDT as a credible and influential theory (Ryan & Deci, 2024).

In brief, according to SDT, humans have an innate drive toward personal growth and psychological well-being; however, these outcomes are dependent upon the fulfillment of three fundamental and universal psychological needs, namely: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2024).

In addition, SDT distinguishes between internal (or intrinsic) and external forms of motivation. Intrinsic motivations reflect a sense of volition or personal choice, while external motivations are driven by environmental controls, social pressures, or the promise of rewards (Ryan & Deci, 2024). According to SDT, individuals acting on intrinsic motivations demonstrate higher levels of engagement, persistence, and overall well-being, while external motivations are associated with reduced engagement, lower persistence, and suboptimal functioning (Ryan & Deci, 2024).

Drawing on SDT’s theoretical framework, researchers and practitioners have designed programs and strategies that foster individual growth and enhance well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2024). SDT principles have also been successfully implemented in educational settings to promote student motivation and learning by emphasizing choice, providing meaningful feedback, and fostering a sense of belonging (Ryan & Deci, 2024). Similarly, in healthcare, SDT has guided interventions that encourage adherence to treatment plans by supporting patients’ autonomy and empowering them to take ownership of their health (Ryan & Deci, 2024).

*SDT comprises six mini-theories, each addressing specific motivational phenomena: cognitive evaluation theory, organismic integration theory, causality orientations theory, basic psychological needs theory, goal contents theory, and relationships motivation theory.

The Human Potential Movement

The Human Potential Movement (HPM) was the conduit through which psychological theories were circulated within popular culture during the 1960s and 1970s (Longe, 2016). Heavily influenced by Humanistic psychology, HPM centered on a belief in an individual’s untapped potential for growth, creativity, and self-actualization (Dillon, 2020). Although not identical to the New Age movement, the two shared parallel goals including personal evolution, raising human consciousness, and exploring altered states (Dillon, 2020; Reber, 1995). HPM also aligned with the counterculture’s ethos of social change by way of self-exploration and emotional expression (Dillon, 2020). Through encounter groups, which were a core component, HPM thus aligned with the two major social movements prevalent at the time, transforming from a therapeutic approach into a broader social phenomenon (Spence, 2007).

Encounter groups evolved out of sensitivity training, a psychological approach developed in the 1940s to increase awareness of emotions, behaviors, and social interactions (Dillon, 2020). Influenced by Kurt Lewin’s research on group dynamics, which aimed to enhance interpersonal communication and group cohesion (Longe, 2016), sensitivity training was applied in corporate settings in the 1950s to improve teamwork and leadership (Reber, 1995). This approach expanded into the self-help movement of the 1960s, leading to the development of encounter groups (Dillon, 2020; Reber, 1995). Encounter groups built upon the foundation of sensitivity training by emphasizing intense emotional expression, self-exploration, and the confrontation of personal biases (Dillon, 2020). In practice, group leaders created an environment that encouraged participants to share vulnerabilities, address personal issues, and engage in transformative emotional release while receiving group feedback (Dillon, 2020).

By the late 1960s and 1970s, HPM’s popularity had spread ‘like wildfire,’ with encounter groups taking place in a variety of settings such as schools, universities, community centers, and so-called growth centers, making them accessible to a broad range of individuals seeking personal transformation (Dillon, 2020; Reber, 1995; Weigel, 2002, p. 192). As the movement gained momentum, HPM’s emphasis on self-expression and openness fostered an increasingly decentralized environment and one that came to include a variety of additional therapeutic techniques. For example, Gestalt psychology, with its focus on living in the ‘here and now,’ gained prominence, as did Transpersonal psychology, with the exploration of ESP and altered states of awareness taking place at institutions dedicated to human potential, such as the Esalen Institute (see below) (Lewis & Melton, 1992; Longe, 2016).

The allure of HPM soon began to transcend professional boundaries, attracting group leaders from diverse fields such as teaching, theology, art, sociology, and social work, along with avant-garde practices like psychodrama, art therapy, dance, bodywork modalities, and biofeedback (Longe, 2016; Reber, 1995; Spence, 2007). Certain HPM groups incorporated New Age spiritual practices such as Zen Buddhism, yoga, and astrology, while others included participants who supported alternative practices like vegetarianism and natural birthing (Stahnisch & Verhoef, 2012).

The decline of HPM by the 1980s has been attributed to several factors, including its disconnect from rigorous research and descent into sensationalism and commercialism (Seaman, 2016). Critics argued that HPM exploited individuals’ vulnerabilities by offering simplistic solutions rather than genuine transformation (Seaman, 2016). A lack of regulation had also led to varying levels of expertise among group leaders, raising concerns about quality and safety, while the commercial success of associated books and workshops, often based on anecdotal evidence, was critiqued as evidence of the movement’s profit motive over authentic psychological benefits (Seaman, 2016).

Despite its decline, HPM has had a lasting impact on American culture, particularly its influence on emotional disclosure, feedback, and interpersonal communication (Dillon, 2020). HPM’s focus on self-exploration also continues to shape the self-help and personal development industry (Dillon, 2020; Longe, 2016). The movement’s influence can be seen in modern therapeutic practices, such as mindfulness-based therapies, which integrate principles of emotional awareness and self-exploration, while its legacy endures in the continued popularity of retreats, workshops, and transformational seminars that promote self-improvement and holistic well-being (Longe, 2016). HPM’s impact on education can also be seen in the development of alternative graduate programs, the incorporation of sensory awareness and emotional intelligence in schools, and experiential education models like Outward Bound, which emphasizes personal growth, teamwork, and emotional resilience (Dillon, 2020).

Esalen Institute

The Esalen Institute is a spiritual retreat center located in Big Sur, CA. Founded in 1962 by Michael Murphy and Richard Price, the Institute contributed significantly to the Human Potential Movement and the exploration of human consciousness.

Its founders, dissatisfied with conventional institutions and particularly contemporary approaches to mental health, created the institute as a hub for the exploration of humanistic psychology, Eastern philosophies and alternative therapies, offering a wide range of workshops and retreats led by psychologists, authors, and spiritual teachers (Longe, 2016).

The institute was endorsed by such luminaries as Abraham Maslow who called it one of the most important educational institutions in the country and in 1971, at the height of Its success, it was labelled “the Harvard of the Human Potential Movement” in a Newsweek cover story (Tackett, 1990). Inspired by Esalen’s success, an estimated 150–200 growth centers modeled after its practices were operating across the United States by the early 1970s (Longe, 2016).

Central to Esalen’s mission was a commitment to facilitating personal and collective growth, and to that end, the Institute continues to support non-traditional practices and treatments. According to its website, and in addition to psychotherapy, the Institute offers acupuncture, bodywork and movement practices, meditation, visualization, and hosts self-help support groups.

PHYSICAL WELL-BEING

In this section we will focus on the two aspects of physical well-being that are addressed not only pillars of wellness but front and center at wellness resorts namely, fitness and diet. In particular, we will be considering how views on these topics have evolved within a socio-historical context, along with notable trends . As you will no doubt note, while an emphasis on physical fitness has been widely integrated as a facet of contemporary life, diet represents an area in which the wellness movement may bee seen as representing a counter point to predominantly negative trends within contemporary society.

Fitness

Prior to the late 19th century, the concept of structured recreational exercise was virtually nonexistent, as the strenuous nature of work in both rural and urban settings naturally integrated physical activity into daily life. Agricultural and industrial labor not only required significant physical exertion, but workdays often extended from sunrise to sunset, leaving minimal time for recreational activities. The Industrial Revolution brought significant changes, shifting labor from rural, agricultural work to urban, factory-based jobs. This transition resulted in lower levels of physical activity among the urban population, as well as introduced the concept of leisure time as a novel facet of daily life.

At the start of the 19th century, health in public discourse largely focused on questions of morality, as good health was equated with moral virtue. “Hygienic religion,” a popular notion of the early 1800s, highlighted the connection between physical well-being and lifestyle choices (Whorton, 2008). Measures such as a restricted diet, adequate fresh air and sleep, and forsaking the “passions of the mind” were ardently promoted over lesser concerns like physical exercise (Whorton, 2014). During the latter part of the 1800s, writers such as Thomas Hughes and Charles Kingsley popularized the idea of ‘Muscular Christianity’—the belief that physical prowess and its pursuits were pathways to moral fortitude in service to God and nation (Whorton, 2014). This concept, set against the backdrop of increasing urbanization and concerns over the moral hazards of city life, propelled exercise into the forefront of hygienic discourse for the first time and led to a surge in weightlifting and gym attendance among men (Goldstein, 1992).

Women in the early 1800s faced another, more pressing concern—both literal and figurative. Health problems associated with the tight-fitting corsets of the time included deformed rib cages, restricted breathing, and damage to the digestive and reproductive organs (Whorton, 2014). Social reformers like Mary Gove Nichols, who lectured on female physiology, challenged conventional norms, rightly arguing that such undergarments not only undermined women’s overall vitality but also hindered their capacity to engage in physical exercise (Whorton, 2014). Although the primary focus of the anti-corset movement was on health and reproductive well-being, it indirectly contributed to the growing awareness of the importance of physical exercise for women. While the majority of ‘respectable’ women would continue to wear corsets for another half-century, Nichols’ ‘oratorical barrage’ and willingness to discuss ‘physiological facts, of a delicate nature’ addressed a gap in women’s knowledge and inspired many like-minded crusaders. The corsetless Bloomer costume, first introduced in the early 1850s, thus became a symbol of the physical liberation of women, leading to increased participation in physical activities from the late 19th century onward.

DIOCLETIAN LEWIS

Diocletian Lewis was a prominent figure in physical education during the mid-19th century. While he practiced homeopathy and lectured extensively on health, he would become particularly well-known for his system of “New Gymnastics” . Lewis sought to create a more inclusive approach to exercise, pioneering a “genteel gymnastics” for women at a time when “it was hardly respectable for a lady to be healthy, much less to engage in sports” (Fletcher, 1965). His system emphasized flexibility, coordination, agility, and grace of movement, and he incorporated light apparatus like bean bags, wooden rings, and dumbbells along with dancing and marching routines (Whorton, 2014). Lewis also established the Normal Institute for Physical Education in Boston in the 1860s, where he trained the first generation of physical education teachers in America, with a significant portion of graduates being women (Whorton, 2014). He also championed women’s physical health by opening the Family School for Young Ladies in Lexington,KY where he implemented a program that emphasized exercise, outdoor activities, and non-restrictive clothing (Whorton, 2014).

Diocletian Lewis was a prominent figure in physical education during the mid-19th century. While he practiced homeopathy and lectured extensively on health, he would become particularly well-known for his system of “New Gymnastics” . Lewis sought to create a more inclusive approach to exercise, pioneering a “genteel gymnastics” for women at a time when “it was hardly respectable for a lady to be healthy, much less to engage in sports” (Fletcher, 1965). His system emphasized flexibility, coordination, agility, and grace of movement, and he incorporated light apparatus like bean bags, wooden rings, and dumbbells along with dancing and marching routines (Whorton, 2014). Lewis also established the Normal Institute for Physical Education in Boston in the 1860s, where he trained the first generation of physical education teachers in America, with a significant portion of graduates being women (Whorton, 2014). He also championed women’s physical health by opening the Family School for Young Ladies in Lexington,KY where he implemented a program that emphasized exercise, outdoor activities, and non-restrictive clothing (Whorton, 2014).

Around the early 1900s, physical exercise also moved from a secondary consideration to a primary one in institutional settings. Physician-authored handbooks on exercise and physical education, with recommendations for both adults and children to engage in such activities as walking, riding, rowing, swimming, and fencing, became more common. The establishment and growth of physical education programs in schools and colleges further reflected the elevated status of exercise, both within education and for overall development.

Fitness trends had also begun to emerge. Between the Civil War era and the 1930s, Indian clubs became a staple in American physical education. Adapted from traditional Indian war clubs and first introduced to Europe by British soldiers, participants incorporated hand-held clubs into gymnastics routines and public demonstrations, performing flowing movements intended to enhance grace, flexibility, and strength.

A German health and fitness initiative dubbed Physical Culture, which promoted physical prowess as an expression of national strength and unity, spread to America via England and would remained influential until at least the 1920s (Whorton, 2014). One of its most prominent champions was the eccentric Bernarr Macfadden, who established several ‘healthatoriums,’ a magazine to promote the movement, and a community he called Physical Culture City. Macfadden’s views, however, such as the promotion of exercise for women and the belief that sex was vital to human well-being—were considered scandalous at the time. As a result, his endeavors ultimately garnered widespread public criticism and legal troubles.

Following World War I, an increase in wealth and leisure time allowed Americans to embrace recreational activities and participatory sports, and these would become staples of everyday life by the 1920s (Whorton, 2014). During the 1930s and 1940s, physical fitness for national strength and military readiness remained a national focus. Spurred by the Great Depression and World War II, the rise of so-called ‘He-Man’ catalogues—mail-order courses offering bodybuilding and strength development instructions—became popular among men in pursuit of muscular physiques or the ‘He-Man in the Mirror’ (Figarelli, 2008).

The post-war prosperity of the 1950s saw an expanding middle class—and expanding waistlines. A portly physique was even considered something of a status symbol among middle- and upper-class men (Figarelli, 2008). Women, however, faced social pressure to conform to the “hourglass” figure popularized by Hollywood actresses (Figarelli, 2008). At the time, exclusive men’s health clubs—offering services like massage, steam baths, and light exercise through passive machines—dotted urban landscapes. Meanwhile, televisions, which had become a central feature of American households, provided daily exercise programming targeting suburban housewives. The most famous of these was The Jack LaLanne Show, which aired from 1951 to 1985. LaLanne, a San Francisco-born exercise and nutrition guru dubbed the ‘Godfather of Fitness,’ frequently featured his wife, Elaine, who demonstrated his exercises.

Public concern over sedentary suburban lifestyles peaked in the mid-1950s when an international study revealed that American children lagged significantly behind their European counterparts in physical fitness. In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued an Executive Order establishing the President’s Council on Youth Fitness in 1956. American adults, however, weren’t fairing much better. A national poll conducted in 1960, found that only 24% of Americans engaged in regular exercise (Stern, 2008).

Such trends set the stage for the transformation of fitness culture in the latter half of the 20th century, however, which included evolving attitudes, increased participation, shifting motivations, and the rise of commercial fitness centers across America. One notable figure in this regard was University of Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman. Inspired by jogging practices he witnessed in New Zealand, Bowerman established a joggers’ club in Eugene, Oregon in 1963. He also promoted the activity to a wider audience through a best-selling book entitled simply, Jogging, that was published in 1966. For women, Kathrine Switzer’s historic participation in the all-male Boston Marathon in 1967, despite concerted efforts by race officials to stop her, not only broke gender barriers but played a significant role in popularizing running for women.

Bowerman’s work would also prove impactful in that it influenced public opinion regarding rigorous forms of exercise at a time when bowling was considered strenuous (Stern, 2008). Bowerman collaborated with cardiologists to conduct controlled studies, later published in reputable medical journals, which validated the health benefits of jogging. Two years later, Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper, an American physician and exercise physiologist, published his groundbreaking best-seller, Aerobics, which likewise had a significant impact on public perceptions and by extension, the fitness industry. In his book, Cooper underscored the health benefits of sustained cardiovascular exercise and provided guidelines for incorporating activities such as running, swimming, and cycling into every day routines.

The 1970s marked a turning point as medical opinion shifted firmly in support of regular exercise and public engagement in it transitioned from a niche activity to a mainstream one (Stern, 2008). This decade saw a sustained rise in jogging as well as racquet sports like tennis and racquetball (Figarelli, 2008; Goldstein, 1992). The rising fame of bodybuilders like Arnold Schwarzenegger raised the stakes for men (Juneau, 2024), while the introduction of Title IX in 1972 significantly boosted women’s participation in sports and fitness activities. Pioneered by Jacki Sorensen in 1969, aerobic dancing spread like wildfire under the enthusiastic influence of a growing network of aerobic instructors. The fitness movement even began gaining traction in corporate settings as companies recognized the benefits of exercise for employee productivity and morale (Stern, 2008).

The 1980s solidified the transformation of exercise into a dynamic phenomenon that intertwined the pursuit of health with beauty standards and social status (Goldstein, 1992). During an unprecedented “Fitness Boom,” participation in regular exercise reached 69% by 1987, while home-exercise equipment sales surpassed $1 billion for the first time (Stern, 2008). Health clubs evolved into social hubs, offering trendy aerobics and jazzercise classes. Buzzwords like “power walking” and “aerobics” became commonplace, and workout attire became a fashion statement in popular culture (Figarelli, 2008). The media also played a significant role, with mainstream magazines, news outlets, and television showcasing exercise programs and toned physiques. Meanwhile, celebrities like Jane Fonda fueled the home workout video explosion, and Olivia Newton-John’s song Let’s Get Physical topped the charts in 1981 (Figarelli, 2008).

The fitness boom of the early 1980s leveled off toward the end of the decade, with the number of fitness clubs declining from roughly 14,000 to 9,000 between 1987 and 1990 (Stern, 2008). The more subdued, less body-conscious zeitgeist of the 1990s also shifted the emphasis from flamboyant exercise gear and workouts to a personalized approach, with individuals seeking customized workout plans and guidance. Popularized in the early 1990s, spinning classes, for example, offered structured, instructor-led workouts that could be tailored to individual fitness levels. This decade also saw the proliferation of personal trainers, as fitness training became recognized as a field of specialized knowledge with professional certifications (Figarelli, 2008).