1 The Wellness Revolution

Learning Objectives

This chapter explores the definition of wellness, a concept that emerged in the mid-20th century alongside related ideas like holistic health and self-actualization as desirable, attainable states.

At the conclusion of this chapter students will be able to:

- Understand wellness as a contemporary concept

- Define Wellness

- Understand how the concept has been interpreted in wellness models

- Describe the socio-economic context in which the wellness revolution emerged over time

What is wellness?

Wellness is a term that encompasses both the pursuit and state of holistic well-being and has been described as an ancient idea in a modern guise (Goldstein, 1992; Global Wellness Institute, 2023). While the term itself dates to European sources of the 17th century (Erfurt-Cooper & Cooper, 2009), associated principles can be traced much further back to ancient civilizations from China, India and Egypt to the Greco-Roman world (Global Wellness Institute, 2023, p. i). It wasn’t until the post-World War II era, however, that the concept began to circulate in contemporary Western culture. New perspectives on physical and mental health that were introduced at this time became fundamental to ideas and practices that have shaped the thriving wellness movement of the 21st century (Global Wellness Institute, 2023).

The physician and public health figure, Dr. Halbert Dunn, sometimes referred to as the Father of the Wellness Movement, re-introduced the term in a journal article entitled High-level Wellness for Man and Society which was published in 1959.

At one time, Americans measured the health of the population… by mortality statistics. As life lasted longer, however, health came to have different meanings, beyond diseases and deaths reported to public health officials. More and more, health came to mean how a person felt

(Burnham, 1989)

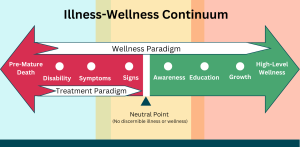

In the article, Dr. Dunn described high level wellness as a holistic approach to achieving optimal health and well-being. His perspective on optimal health was progressive for its time as it marked a departure from traditional models of health care that focused on the eradication of disease and dysfunction (see Figure 1 below).

Dunn’s ideas were influenced, at least in part, by Croatian Dr. Andrija Štampar a prominent figure in the field of social medicine and public health. Following World War II, Dr. Štampar played a pivotal role in the founding of the World Health Organization (WHO). In 1946 the WHO’s Constitution, signed by 61 governments, came into effect and included Dr. Štampar’s definition of health, which Dunn quoted in his seminal article cited above. The definition read as follows: “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity.”

The beginnings of a similar shift in the field of psychology was sparked by the publication of Abraham Maslow’s influential article A Theory of Human Motivation published in 1943. Maslow sought a more holistic understanding of the human experience and believed that existing models of mental health focused too heavily on pathology (Koznjak, 2017). Maslow would go on to co-found the branch of Humanistic psychology which likewise emphasized the positive dimensions of human nature including an individual’s potential and inherent capacity to lead a fulfilling and meaningful life (Waterman, 2013). As we shall see, related ideas would become an integral part of the wellness movement’s ethos and ideas concerning human potential and holistic well-being.

Figure 1: The Illness Wellness Continuum (Source: John Travis, 1972)

Wellness Defined

Before we proceed, let’s consider a definition of wellness. In fact, there are numerous definitions applied in as many contexts. In this course, however, we will adopt the definition provided by the Global Wellness Institute, as indicated below.

Wellness Definition

Wellness is the active pursuit of activities, choices and lifestyles that lead to a state of holistic health.

We should also distinguish between the terms wellness and well-being as these are closely related but not entirely interchangeable. Wellness refers to the concept of holistic health and is typically used as a descriptor (e.g. wellness spa or wellness program) for the places, activities, products, and services that support it. Well-being, on the other hand, refers primarily to the state or subjective experience of wellness and is best described as a frame of mind or psychological condition (Hjalager et al., 2011).

The above definition of wellness, while simple and succinct, includes two key concepts that we will explore further. First, wellness is described as an active pursuit. In other words, it implies deliberate efforts or personal volition in engaging in activities that contribute to overall health and well-being. This could include adopting a healthier lifestyle through nutritious eating habits, setting goals for fitness or personal growth, or taking steps to maintain a balanced mental and emotional state.

This idea is closely related to a fundamental conception that individuals bear primary responsibility for maintaining their health and well-being (Goldstein, 1992). Dr. John W. Travis, a trained physician and holistic health pioneer, was an early proponent of wellness and had a significant impact on the movement. He is also credited with coining the term self-responsibility to highlight individual agency in pursuing and maintaining personal well-being. In 1977, another prominent figure in the wellness movement, health professional and author Donnald B. Ardell, published a book entitled High Level Wellness: An Alternative to Doctors, Drugs, and Disease. Like Dr. Travis, Ardell emphasized personal volition as a central determinant of one’s ability to achieve and maintain well-being. In his book, Ardell presented a model of wellness with four dimensions: (1) nutritional awareness, (2) environmental sensitivity, (3) stress management, and (4) physical fitness, placing self-responsibility at center. As we shall see, the idea of intentional efforts to enhance well-being is also integral to the definition of wellness tourism, distinguishing it from other niche forms of travel or tourism offerings (see Chapter 5: Introduction to Wellness Tourism).

The term (holistic) comes from its root word, ‘whole, ’ and is used to describe everything from alternative medical treatments to new age philosophies. But applied to spas, holistic suggests a program of health and wellness oriented toward a ‘whole life’ attitude

(Jeffrey, 1989)

Second, the above definition includes the term holistic health. In 1961, Dunn published his book entitled High-level Wellness based on a series of lectures and articles he had produced in 1950s. In the book, Dunn described a holistic approach, which he suggested was necessary for an individual to achieve ‘peak wellness’, in terms of the health and integration of the mind, body and spirit within a supportive environment. Such ideas were echoed by others wellness proponents, including Dr. Travis who likewise underscored the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of the body, mind, emotions, and spirit for achieving and maintaining overall well-being. Therefore, holistic health advocates for an approach that considers the whole person—encompassing physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions—while also accounting for external factors such as environmental, social, professional, and familial conditions. It further emphasizes the interconnectedness of these dimensions, recognizing that one dimension can significantly impact others, ultimately supporting or hindering an individual’s overall well-being.

Wellness Models

In the decades following the introduction of the concept wellness, a plethora of models within public and private institutions including areas such as healthcare, education and psychology, were developed to articulate the scope and complexity of holistic health. The National Wellness Institute’s (NWI), for example, published the Six Dimensions of Wellness Model in 1976 which identified the primary dimensions of holistic health, as: (1) physical, (2) emotional, (3) intellectual, (4) social, (5) spiritual, and (6) occupational. The NWI model, still widely used today, was developed to provide a framework for wellness practitioners, community health programs, and private organizations to assess and support individuals’ well-being.

Another well-known model, the Wheel of Wellness (WOW), was developed for use in clinical settings. Introduced in 1991, revised in 1992 and again in 2000, WOW depicts no less than twelve interrelated personal components, seven environmental factors, and five life tasks to depict holistic well-being. Rooted in human development, the model was devised as a framework for understanding and promoting health and wellness across the human lifespan. WOW is used by counselors in schools, colleges, employment and rehabilitation agencies to administer wellness assessments as well as develop strategies to promote positive change. It too remains popular today.

As the above two examples illustrate, wellness models can vary considerably based on their conceptual framework and intended purpose. Some of these variations, however, are more semantic than substantive. For instance, a dimension labeled “intellectual wellness” in one model may be designated as “mental wellness” in another, with little distinction between them. Therefore, rather than examine each wellness model individually, we will consider the most common themes below (see Table 1). Note that some dimensions of wellness are individual, such as emotional, physical, or intellectual wellness, while others involve external or environmental factors like social, occupational, and environmental wellness, underscoring the vital importance of connection to others, one’s surroundings, and broader societal influences on individual well-being. The other key takeaway is that wellness is multi-dimensional, requiring a multi-faceted or integrated approach to achieve. While the designation of certain dimensions is consistent across models, the inclusion of others is often shaped by the specific context or goals of the model, rather than by a universally agreed-upon standard for what constitutes wellness.

Table 1: Wellness Models Themes

The Wellness Revolution

In the following section, we will briefly consider the societal context in which the concept of wellness evolved into a wellness movement. Specifically, this section highlights a range of cultural influences and societal developments that transformed a paradigm shift in the definition of physical and mental health into a 21st-century megatrend. From the mid-20th century onward, related concepts began to take root within the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which were subsequently absorbed into popular culture during the 1980s. The transformation of wellness from a niche concept into a central part of daily life reflected broader trends toward self-care, preventative health, and personal empowerment. The 1980s also marked the start of the wide-scaler commercialization of wellness that would eventually give rise to a global, multi-billion-dollar industry, as highlighted in Paul Zane Pilzer’s bestseller The Wellness Revolution (2005) by the dawn of the 21st century.

Figure 2: Milestones in the wellness revolution

The use of psychedelic drugs, particularly Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), and psilocybin mushrooms, became closely associated with the counterculture movement of the 1960s. An embrace of psychedelics was rooted in the belief that they offered a remedy for societal alienation and a pathway to spiritual awakening. Psychiatrist Dr. Stanislav Grof, a well-known figure in the field of transpersonal psychology and holotropic (moving towards wholeness) breathwork, for example, espoused the therapeutic benefits of LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) based on research with his patients. Growing skepticism and concerns about the potential dangers associated with psychedelic drugs like LSD, however, led to legal restrictions and a shift in public perception in the late 1960s and early 70s. Even today, the use of these substances in therapeutic settings remains controversial and supporters are generally not mainstream, however, a notable resurgence of interest in psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs has been supported by promising results in forms of therapy such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in recent years (Yasinski, 2022). The growing use of the psychedelic ketamine along with a surge in the number of ketamine clinics in the past five years, is another example of both the success and growing acceptance of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes (Tafra, 2023). Research on the use of psilocybin in recent decades has also proven promising, and there is considerable support for this natural, ancient remedy from within the wellness community.

The use of psychedelic drugs, particularly Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), and psilocybin mushrooms, became closely associated with the counterculture movement of the 1960s. An embrace of psychedelics was rooted in the belief that they offered a remedy for societal alienation and a pathway to spiritual awakening. Psychiatrist Dr. Stanislav Grof, a well-known figure in the field of transpersonal psychology and holotropic (moving towards wholeness) breathwork, for example, espoused the therapeutic benefits of LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) based on research with his patients. Growing skepticism and concerns about the potential dangers associated with psychedelic drugs like LSD, however, led to legal restrictions and a shift in public perception in the late 1960s and early 70s. Even today, the use of these substances in therapeutic settings remains controversial and supporters are generally not mainstream, however, a notable resurgence of interest in psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs has been supported by promising results in forms of therapy such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in recent years (Yasinski, 2022). The growing use of the psychedelic ketamine along with a surge in the number of ketamine clinics in the past five years, is another example of both the success and growing acceptance of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes (Tafra, 2023). Research on the use of psilocybin in recent decades has also proven promising, and there is considerable support for this natural, ancient remedy from within the wellness community.

The 1970s is often referred to as the “Environmental Decade,” as it marked a significant surge in environmental awareness and witnessed major policy initiatives, the establishment of Earth Day, and the passage of landmark environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. The decade also saw the rise of the popular environmental movement, driven by concerns over pollution, environmental degradation, and the impacts of industrialization on public health. This movement emphasized the interconnectedness of human health with the health of the planet, encouraging eco-friendly practices and sustainable living. In addition, growing awareness of the importance of nutrition, exemplified by books such as Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappé, highlighted the link between environmental and human health and sustainable eating practices. As part of a broader shift within the wellness movement, this period thus also saw an increased embrace of whole foods, natural, organic, and plant-based diets.

The 1970s is often referred to as the “Environmental Decade,” as it marked a significant surge in environmental awareness and witnessed major policy initiatives, the establishment of Earth Day, and the passage of landmark environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. The decade also saw the rise of the popular environmental movement, driven by concerns over pollution, environmental degradation, and the impacts of industrialization on public health. This movement emphasized the interconnectedness of human health with the health of the planet, encouraging eco-friendly practices and sustainable living. In addition, growing awareness of the importance of nutrition, exemplified by books such as Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappé, highlighted the link between environmental and human health and sustainable eating practices. As part of a broader shift within the wellness movement, this period thus also saw an increased embrace of whole foods, natural, organic, and plant-based diets.

The first ever podcast launched in 2003. A few years later, wellness podcasts such as The Daily Boost by Scott Smith (2006) began streaming. The Daily Boost, which focuses on motivation, personal development, and wellness, is still running today. Other wellness podcasts soon followed including one dedicated to wellness travel. Cheryl MacKinnon is host of The Wellness Travel Show that streams on

The first ever podcast launched in 2003. A few years later, wellness podcasts such as The Daily Boost by Scott Smith (2006) began streaming. The Daily Boost, which focuses on motivation, personal development, and wellness, is still running today. Other wellness podcasts soon followed including one dedicated to wellness travel. Cheryl MacKinnon is host of The Wellness Travel Show that streams on