4 Dissection of a literature review

The stand-alone literature review

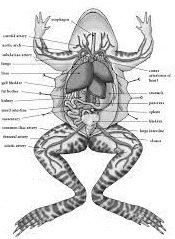

In most sophomore biology classes in high schools, students are asked at one point to cut open a frog, identify the various internal organs and draw a diagram of what they find. This exercise is my intention here. I will be cutting open and revealing to you the requisite parts of a literature review. In the following section we will dissect an article that was written as a stand-alone literature review. The purpose of the literature review as its own article is to tell us where we have been on a topic, and to light the way for where the field should go next.

This specimen we will be dissecting was written by De Veirman, Hudders, and Nelson (2019). Their research focuses on the literature of social media influencers’ impact on children. Excerpts are provided for our dissection, but you can find the full article here:

De Veirman, M., Hudders, L., & Nelson, M. (2019). What is influencer marketing and how does it target children? A review and direction for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

What is influencer marketing and how does it target children? A review and direction for future research

Children nowadays spend many hours online watching YouTube videos in which their favorite vloggers are playing games, unboxing toys, reviewing products, making jokes or just going about their daily activities. These vloggers regularly post attractive and entertaining content in the hope of building a large follower base. Although many of these vloggers are adults, the number of child vloggers is flourishing. The famous child vlogger Ryan of Ryan’s World, for instance, has more than 19 million viewers and he is (at age seven) a social media influencer. The popularity of these vloggers incited advertisers to include them as a new marketing communication tool, also referred to as influencer marketing, in their marketing strategy. Accordingly, many influential vloggers now receive free products from brands in return for a mention in one of their videos and their other social media (e.g., TikTok or Instagram) and some are even paid to create a sponsored post or video and distribute it to their followers. This sponsored content appears to be highly influential and may affect young children’s brand preferences. Given the limited advertising literacy skills (i.e., knowledge of advertising and skills to critically reflect on this advertising) of children under age 12, they are a vulnerable target group when it comes to persuasion. Therefore, caution is needed when implementing this marketing tactic to target them. However, research on how influencer marketing affects young children (under 12) is scarce and it is unclear how these young children can be empowered to critically cope with this fairly new form of persuasion. This paper therefore aims to shed light on why and how social media influencers have persuasive power over their young followers. The paper starts with providing insights into how and why social media influencers became a new source in advertising. We then discuss the few studies that have been conducted on influencer marketing among young children (under 12), based on a systematic literature review, and take these findings to formulate societal and policy implications and develop a future research agenda.tent here.

In this introductory paragraph, the authors achieve three main goals. First, they provide needed background information on the issue as a contemporary problem. This article is focused on the practical implications of the theories they will summarize in this literature review. Notice they mention the various forms of media and influence and provide some examples. Second, they provide insights as to why this might be problematic, socially. They are making the case here for why research needs to be summarized so that this population of consumers can be better served (and protected). This leads them to the third goal which is to describe how their summary addresses the problems outlined in the second goal. Take note of the clearly identifiable thesis found at the end of the introduction – “This paper therefore aims to shed light on why and how social media influencers have persuasive power over their young followers.”

order to adopt a theoretical approach to children’s processing of influencer marketing, we draw upon existing theoretical and empirical work regarding source effects in persuasion. During

childhood, children encounter different advertising sources shaping their tastes and preferences, trying to turn them into brand loyalists as they grow older. Social media influencers

can be perceived as a new type of real-life endorser affecting children’s and their parents’ consumption behavior. Second, this paper provides a review of the current (limited) academic

research on influencer marketing targeted at children. Additionally, societal and policy implications of this tactic in the context of prior research are discussed. Third, a future research agenda that may foster academic research on the topic is included. This way, we hope our review may provide a basis for marketing related regulation, policies, and parent intervention strategies and thus help ensure the protection of children.

The authors continue with a longer introduction to the literature review by providing specific case studies and citing the relevancy and dangers of the issue. They conclude that section with the following paragraph. You can see the practical implications of summarizing the research, and the need for the literature review in that the field is just growing and has a wide breadth of topics which have not been synthesized. This is an immature research fields that needs a scholar to categorize into themes and research tracks. The future research agenda is the primary outcome of such a literature review, but must be bolstered by the findings of the literature review itself.

expertise refers to the endorser’s competence, knowledge, and skills (Hovland et al., 1953; Sternthal et al., 1978; Erdogan, 1999; Flanagin and Metzger, 2007).

The authors now begin their review of the literature by citing the original thinkers (seminal authors). You can usually pick out seminal works by the date. A robust description of the seminal work is not needed because others reading your work will be well familiar with them. Laswell (1948) began the discussion on communication in advertising. Because this literature review is focused on advertising to children through social media influencers, this seems like a logical beginning to their literature review. Other ideas generated by early works are also cited. Stern’s (1994) work on branding, Sternhal et al’s. (1978) research on credibility in advertising, and Hovland’s (1953) empirical investigations of trustworthiness and expertise all become solid starting points for this literature review. The principles theories of these seminal works are tangentially related to the research project at hand. However, the constructs and dynamics of these theories apply in the same manner to the traditional advertising as they do for social media influence on children – that is, how is media being consumed?

The authors continue by exploring the field of advertising and the dynamics of theories which apply to influencing. The seminal theory of Badura (1966) on social cognition (that is, how do we learn from each other) is directly impactful on how children are being influenced by media. The last sentence of this section provides transition to the next section, which is good employment of academic writing.

The following three sections of their literature review are structured as follows:

In the next section of the literature review, the authors provide an overview of the various influencing methods which target children which include brand and licensed characters as well as celebrity and peer endorsers. In the subsequent section the authors provide an overview of social media marketing in general, with emphasis on how influencers have become credible advertising means, relatable role models, and hidden persuaders. They then establish an understanding of traditional advertising targeting children. Building upon the theories outlined in these first sections, they conclude by providing a synthesis of the literature as it relates to current research on influencer advertising towards children.

disclosure was included to alert children on the inclusion of advertising. In a between-subjects design, 151 children (9–11 years) were exposed to popular YouTubers’ vlogs including a non-food product, or an unhealthy snack with or without an advertising disclosure. Participants’ intake of the marketed snack and an alternative brand of the same snack were measured. In line with their first study, influencer marketing increased children’s immediate intake of the promoted snack relative to an alternative non-food brand (control condition). Remarkably, the inclusion of an advertising disclosure increased the effect, as children who viewed food marketing with a disclosure (and not those without) consumed 41% more of the promoted snack compared to the control group. The study of De Jans et al. (2019) examined how an educational vlog can help children (11–14 years) cope with advertising. In an experimental study (N = 160), using a two (advertising disclosure: no disclosure versus disclosure) by two (peer-based advertising literacy intervention) between-subjects design, they examined how an advertising disclosure can reduce the persuasiveness of sponsored vlogs and how watching an educational vlog moderates these effects. The results show that an advertising disclosure increased their recognition of advertising and their affective advertising literacy for sponsored vlogs, and that only affective advertising literacy negatively affected influencer trustworthiness and PSI and purchase intention accordingly. Moreover, when young adolescents were informed about advertising through an informational vlog (i.e., peerbased advertising literacy intervention), positive effects on the influencer and subsequently on advertising effects were found of an advertising disclosure. Evans et al. (2018) examined how parents of young children cope with sponsored vlogging on YouTube. They gauged parents’ understanding of and responses to sponsored child influencer unboxing videos. Through an experimental design among 418 parents, they assessed the influence of sponsorship text disclosure (present or absent) and sponsor pre-roll (sponsor pre-roll, nonsponsor pre-roll, and no pre-roll) for a toy on conceptual persuasion knowledge, perceptions of sponsorship transparency, and different outcome measures. Moreover, they explored how parental mediation influences the outcomes. They found that sponsor variations in pre-roll advertising (sponsor versus nonsponsor versus none) and sponsor text disclosure (present versus absent) conditions did not affect parents’ conceptual persuasion knowledge of the unboxing video. However, if a sponsor pre-roll ad was included, parents reported higher levels of sponsorship transparency of the unboxing video compared to parents who saw no pre-roll ad or a nonsponsor pre-roll ad. There was no additional effect on sponsorship transparency or conceptual persuasion knowledge when a sponsor text disclosure was included. Moreover, high levels of parental mediation conditionally impacted the indirect effect of a sponsor pre-roll advertisement via sponsorship transparency on perceptions of the unboxing video and attitudes toward the sponsor.

The conclusion section follows which emphasizes the implications for both society and what regulators can do to prevent some of the dangers associated with the influence of children. They make recommendations on future research in subsequent sections on influencer marketing strategies, the impact of influencer marketing on minor audiences, empowering children, and protecting children.

interests. Most prior research focused on children’s exposure to and perception of influencer marketing. The above studies show that children spend a lot of time watching videos of their favorite influencers, in which they also encounter influencer marketing practices (e.g., Marsh, 2016; Folkvord et al., 2019; Martínez and Olsson, 2019). Moreover, they are also influenced by the content these influencers post and susceptible to the commercial messages incorporated in it (e.g., Folkvord et al., 2019; Martínez and Olsson, 2019), specifically those on (unhealthy) foods and beverages (e.g., De Jans et al., 2019;Coates et al., 2019a,b). Considering children’s susceptibility toinfluencer marketing practices, the findings of the above discussed prior research support the importance of existing guidelines and regulations stressing the fact that advertising should be recognizable as such, in particular for minor audiences. Two studies (De Jans et al., 2019; Coates et al., 2019b) tested the impact of an advertising disclosure on minors’ recognition of and susceptibility to influencer marketing. While both studies have shown that the inclusion of an advertising disclosure helps children recognize advertising, the study of Coates et al. (2019b) found that this increased recognition actually increased the effectiveness of influencer marketing, resulting in a higher intake of the promoted snack. Moreover, De Jans et al. (2019) found that the inclusion of an advertising disclosure may have positive effects on the influencer and subsequently on advertising effectiveness when minors were informed about advertising through an advertising literacy intervention in the format of an informational vlog. These studies suggest that a disclosure indeed helps children recognize influencer marketing practices as advertising and thus protects children from subconscious persuasion, without necessarily having a negative impact on the influencer and advertising effectiveness. In addition, Evans et al. (2018) found that sponsorship transparency in child-directed content is also appreciated by parents and has a positive effect on parents’ perceptions of unboxing videos, attitude toward the brand, and attitude toward the sponsor.

Literature review as part of a full paper

The following section is a dissection of an actual literature review which was crafted as part of an article entitled “The Halloween indicator is more a treat than a trick” which was published in the Journal of Accounting and Finance (2017). For context, this article was a research piece on the “Halloween indicator” which is a stock market phenomenon whereby investing slow down in the summer and pick up in the fall (right around Halloween). The authors conducted a quantitative analysis of the Halloween indicator in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

We will dissect each section and call out the progression of the literature review – beginning with seminal works and following the nuances, debates, controversies, modern understandings, and most importantly, how the empirical research study being conducted adds to the body of knowledge (remember, we are making an ever so slight bump on the edge of the sphere of knowledge). It is only after identifying the shoulders of giants, and the gaps in understanding that authors can make the case for why their research is important and relevant. Excerpts of the article’s literature review with annotations are captured here.

The literature review section of this article begins:

The authors tip their hat to a seminal work, that of Bouman and Jacobsen (2002) who conducted an exhaustive study on the Halloween indicator. They are widely recognized as being the first major review of the issue and are considered a veritable seminal work. Their work spurs investigation not only into the summer-fall calendar anomaly in stock markets, but other seasonal anomalies as well.

Finally, the authors make their case for why and how the study they are conducting advances knowledge on the issue. Notice that research articles can advance understanding in more than one way at a time. This study investigates the issue after a major crisis to see if it still exists, then provides a practice recommendation, and finally explains the origins of the phenomenon.