6 Practical Guidance

Climbing Mount Everest

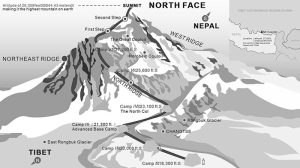

In 1953, Sir Edmund Hillary and his Sherpa mountaineer guide Tenzing Norgay completed the first documented ascent of the highest mountain on our planet – Mount Everest. By 2023, only 7,000 human beings had repeated the accomplishment. Many people fail and too many die in their attempts. The rare climber who achieves this extraordinary feat garners social admiration both within the climbing community and outside. Making it to the top means enduring the oxygen deprived-atmosphere, enormous physical barriers of crevasse fields and sheer rock walls, unceasing uneasiness and psychological fears, and the volatile Himalayan weather that stops expeditions without notice. Perhaps most hindering of all is the short weather window (5-6 days of clear weather in the month of May). Starting too soon and the snow and cold impede progress, too late and the melting snow and softened ice fields create unmanageable fall hazards. Despite these elements throwing themselves at the climbers every step of the 29,032 foot climb, climbers engage in a practice which substantially improves their odds of a successful summit. That is, they acclimatize. The limited oxygen at altitude demands acclimation – climbers need to spend time allowing their bodies to function on less oxygen (anerobic respiration).

An assault on the mountain begins by hiking 40 miles to Camp 1 (about 18,300 feet). They spend several days at Camp 1 before making their first climb to Camp 2 (about 20,000 feet). Incredibly, the mountaineers spend the night at Camp 2 before returning to Camp 1 the next day. It seems redundant or a waste of time and precious, oxygen-deprived energy to climb 1,700 feet to Base Camp 2, only to return. The process is repeated between Base Camps 2, 3, 4, and 5. However, these meta-steps are absolutely necessary for the human body to properly prepare for high altitude adjustment. By the time they reach the death zone (above 26,000 feet), climbers have maximized their bodies’ chances of making it to the summit through these previous up and down expeditions. “Mountaineers the world over follow a simple maxim: “climb high, sleep low.” The idea is to expose the body gradually to higher and higher altitudes, forcing it to adjust, and then returning back down to sleep and recuperate at an altitude that the body is already used to.” (Cunietti & Galanti, 2023). By the time a climber finishes the last step of the 29,032 foot climb, they have actually climbed the mountain 3-4 times.

(Source: Tibet Travel, Everest Maps)

An important lesson looms here for us, flat-land walking, sleep-in-a-bed every night kind of folks. If we want to achieve more advanced writing, better term papers, more credible journal publications, and acceptable dissertations, we need to engage in a similar process of acclimation. In this metaphor, we can visualize how to progress from undergraduate lower level courses to your upper level ones, the transition from bachelor’s studies to masters, and a jump to the pinnacle of academic writing – doctoral writing, book authoring, and journal publications. As you begin each leg of the journey, you need to hike up to the next base camp to get comfortable with what the new standards and expectations are. What does this mean on a practical level? When you write your first undergraduate term paper, take your first draft to a tutor, professor, or peer who writes well. Understand and internalize this feedback deep enough to replicate it the next time your write. If you get comments that your thesis needs work, ask questions about how to improve exactly. See if the professor will share examples of good theses, either from other students or previous semester “A quality” papers. When working on your master’s thesis or doctoral dissertation, look at successfully defended ones. Most schools have a repository that houses these documents. Read them, replicate their phrasing, ask the authors questions about their process. When you set a goal to publish in the top journals, start with the lower level ones. Practice getting feedback from reviewers by traying to understand every component of their feedback. “Climb high” means learning from the next level up you want to achieve, while “sleep low” means returning to the task at hand and apply what you have learned. In this section we provide practical guidance on how to adjust to the higher altitude that each level of complexity that academic writing demands from us. Allow this feedback to be your guide to the summit of whichever goal (your personal Everest) you have set for yourself.

Read and imitate

A quick story best illustrates our first practical guidance. Pia was a senior in college when her little brother Hans enrolled as a freshman. He was taking the English composition class that all freshmen take, and he asked his older sister if she would proofread his first essay. After reviewing the paper, she saw how horrendous his writing was and how poorly his composition was constructed. So she marked it up a bit, and gave it back to him. “The paper is terrible, but I have good news and I have bad news,” she determined. “The bad news is that the paper is terrible, but the good news is that you are not a bad writer, you are a bad reader.” Her point was that writing is a result of reading. We are not born knowing a language, and we certainly don’t wake up knowing how to write well. We learn spoken language by imitation and observation. This is how we learn our local idioms and regional vocabulary as native speakers of our own language. Dad yells something out at a football game, and the next time you are watching a game, you repeat it, with a fairly confident understanding of what it means and when to use it. Writing is the same way. We imitate good writing only in the contexts of reading that we expose ourselves to. In this case, a lack of reading lead Hans to write how he spoke.

Simply stated, the most effective method for improving your writing is to read. Think about our climbers. Reading is the training they do before they even get to the base of the mountain. In a way, what you read doesn’t really matter. The fact that you are reading does. Try reading all of the assigned chapters in your textbook. Read ESPN news articles. Read the USA Today. Read 100 journal articles from the journal you are targeting for your next publication. Reading allows you to see use of advanced language, new vocabulary, transitional phrasing, and perhaps infusion of personal perspective and critical conclusion drawing without violating the objectivity objective of good research. Read and imitate, then read some more. You will slowly, organically pick up on the habits of outstanding authors – how they vary long sentences with short ones, construct complex use of subordinate clauses, qualifying statements, along with simple stating of ideas. This reading is your preparation for the more advanced writing you will progress towards. This is your altitude gain in our Everest analogy, and will acclimate you to more advanced writing. Climb high, sleep low.

Avoid these pitfalls

Successfully standing on the top of Mount Everest requires unwavering commitment to safety protocols. There are certain behaviors that are imperative to avoid if you want to live. For example: never detach yourself from the rope, never be in a hurry, check harnesses, check knots, and the like. Similarly, good writing has danger areas (or behaviors you want to avoid). One of these behaviors you want to eliminate is called “data dumping.”

The purpose of a literature is not simply to serve as a list of everything that has been studied in a single field. An effective one synthesizes, summarizes, and integrates the varying developments and perspective on a given topic. Resist the urge simply to “data dump” whereby you start going through authors one by one “Smith (2002) found . . . . . Jones (2006) discovered . . . . Martin (2012) concluded . . . .” Instead try to find themes and general trends that can be categorized and presented in a coherent manner without overwhelming the reader with the facts of scholarly articles.

Avoiding dangers and travelling safely is the only way to sustainably move up and down between base camps. Climb high, sleep low.

Fake it

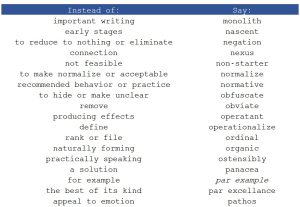

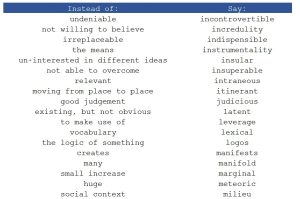

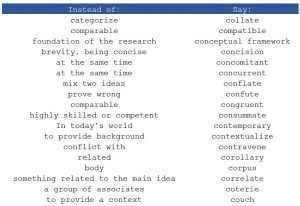

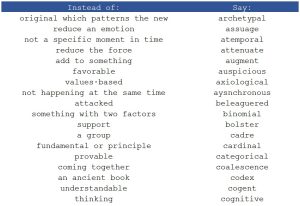

No doubt, climbers on their attempt of Everest get scared. They would not be human otherwise. They must move forward despite the fear as they place one crampon in front of the other, dangling from an ice wall. One strategy to deal with this is to fake it. Act like you belong. Act like you’re not scared and keep moving. The same holds true for making progress in academic writing. While reading allows you to internalize and repeat good writing, you can fake it in the meantime by applying a handful of “academic” words in your writing that will instantly improve its quality. There are four categories of substitutes that can serve as shortcuts while you are in the “fake it” stage. These include single word synonyms, alternative phrasing for citing research, unique ways to improve references, and transitional phrasing.

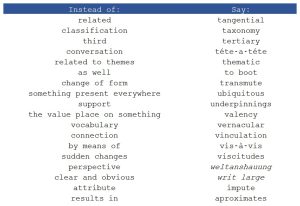

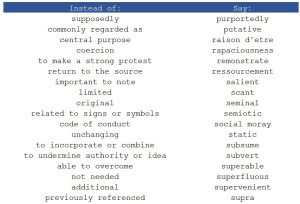

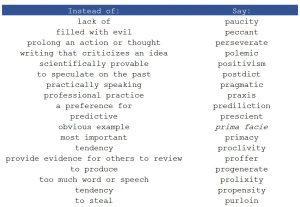

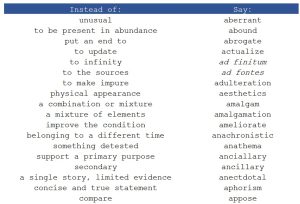

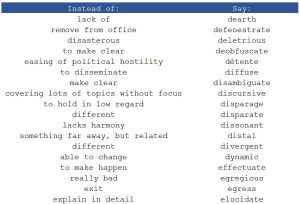

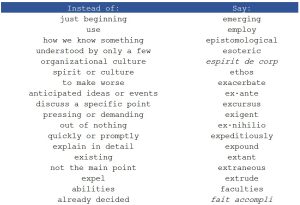

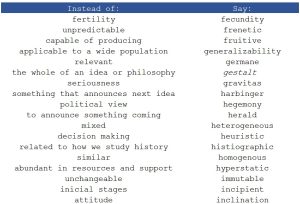

Alternative wording would include substituting the word “update” with the word “actualize,” or “support” with “bolster.” A word of caution here – be hesitant to simply find alternatives in a thesaurus without context. Look for sample sentences using words you find in thesaurus. Otherwise the use of the synonym you chose could be awkward, or worse, wrong. Some words require distinct prepositions to accompany them. This is why reading is important to reinforce usage. For example, you might find the word “augment” as a synonym to “add” and write the following sentence:

Supervisors augment to the culture by using emotional intelligence.

In this sentence the word augment has both an incorrect preposition (it actually doesn’t require one) as well as incorrect application towards the object. Augmenting usually means adding to something that can be quantified – like income, or scores, or data. Its ok to try new words, and even better to use them correctly. This takes practice and reading, but is an easy first step in improving your writing. Consider the following list of substitutes for common phrasing. In your next term paper, or academic paper, make an attempt to substitute three new words you have never used before. And then use the same three words in the next one, adding three more words.

The second way to fake it is to find alternative ways to reference the research or the body of knowledge on a particular subject. Often, undergraduate students will use the following phrase in their term paper, “An article I found talks about . . . .” There are more sophisticated and easily applicable ways to fix this. Instead of starting with “an article”, instead focus on synthesizing several articles and state “Research shows that. . . . “ and then provide individual citations. Consider the following comparison:

An article I found talks about how people should be more aware of emotions at work (Jones 2016). Another one showed how a manager would have employees who are more willing to be a part of the team (Smith, 2020).

This is clearly a poor a use of academic language. Instead start with a broad statement on the research, such as:

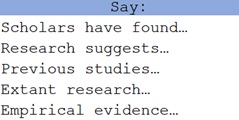

There are a few phrases that can be “faked” as you learn to become a good writer. Each of these need to be followed by citations of what the research has to tell us. If you make a statement which needs to be substantiated by a research citation, a reviewer or your teacher might respond “says who” or “which research.” Use the following phrasing, followed by your citations of what the research shares.

A common practice in the follow up of these statements is to provide a handful of individual contexts to which it applies. Remember that we need to synthesize what the research has found, but in some circumstances, we can show the variety of topics that the research covers outside the main themes. You can list these in a single sentence and then provide the citations in order at the end. Consider the following:

Empirical evidence suggests that corporate social responsibility impacts a wide scope of stakeholders. Research shows that corporate decision-making has a considerable impact on employees, customers, suppliers, and creditors (Hooks, 2004; Tackleberry, 2001; Hightower, 2021; Mahoney; 2015).

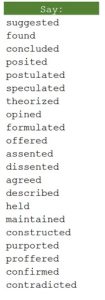

A third approach to faking it is to avoid the use of the word “said” when citing author’s work. “Lonestar (1985) said that . . . .” or “Barf (1978) said that . . . .” Instead, there is a long list of action verbs you can borrow from, depending on what the author actually said – did they confirm something, did they discover something, did they disagree?? Instead consider “Vespa (1987) offered that . . .” or “Skroob (2019) discovered. . . .”

Use the following list to cite individual sources, and avoid “said.”

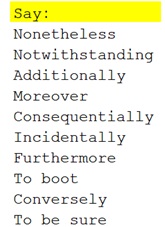

Finally, academic writing requires flow. Long sentences, short ones, and good transitional phrasing to connect ideas. An easy way to fake this composition is to add conjunctive adverbs to the beginning of sentences sporadically throughout the paper. Undergraduate students attempt to do this with the trite phrase “With that being said. . . “ Instead, when adding to an existing train of thought, start a sentence off with “Moreover, . . . .” and when introducing an opposing viewpoint, start with “Contrarily, . . . .”. Consider the following list of transitional phrasings:

Engaging in these behaviors (substituting words, referencing research, transitions, and in-text citations) are the writing equivalent of climbing to Camp 2 while you acclimate to the altitude of good writing. Climb high, sleep low.