8 Controlling

Learning Objectives

The purpose of this chapter is to:

- 1) Introduce the control process

- 2) Discuss the time and types of control processes

- 3) Explore the overuse or underuse of the control function

Controlling

Control is installing processes to guide the team towards goals and monitoring performance towards goals (Batemen & Snell, 2013). The purpose of the control function is to ensure that the organization makes progress towards the established goals. This is done prior to implementation of the gameplan as a manager anticipates what might go wrong. Control is done during the process of implementation as the manager monitors the progress and makes changes as needed. As such, the control function of management is highly intertwined with the planning phase. The guides that managers use to ensure progress and the mechanisms used to monitor progress are areas that need direct consideration before the plan implementation begins.

A good analogy for the control process is a road trip. In this analogy the goal (planning) is to drive from Kansas to Missoula, Montana for a bluegrass festival. To go on this roadtrip, you have a budget for gas and gas station food (organizing), and you have convinced your best friend to join you (leading). You have three days to get there for the start of the festival. The controlling function in this road trip is to ensure that you will make it to Missoula in time for the start of the event. In the planning phase, this would include checking the oil, checking the tread on your tires, and checking the windshield wipers. These steps improve the likelihood that you will get to your destination. Based on your estimates, you have decided that you need to drive 9 hours per day over the two days you have allotted for this trip. During the trip, you monitor the gas gauge and each time it falls below the ¼ tank range you find the next stop to fuel up. During the trip, your GPS identifies an accident that is delaying traffic outside of Denver. The GPS suggests you reroute to save an hour by going on the toll way. The first day you drive 5 hours because you decided to stop at REI in Denver. Because you are behind schedule, you decide to start the second day at 6am to make up the extra hours. Each of these pre-trip checks and adjustments during the trip are considered control mechanisms. They help you guide the trip, and to monitor progress towards the goal.

Control Process

One of the fundamental elements of the control function of management is to monitor progress. Monitoring progress implies that you need a standard against which to judge whether you are making progress. There is a specific process that allows you to do this, known as the control process.

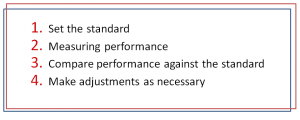

Figure 8.1 The Four-step Control Process

The control process begins with the standard or goal to reach. This portion of the control process is done during the planning phase of management. The standard could be to improve sales by 14%, reduce turnover in Q1 by 1%, improve our season win total by 4 games, reduce batch rejection rates on manufacturing output, etc. This standard includes both the end goal, but more complex goals require mile posts along the way. For example, a 14% improvement in sales over the course of a year means that monthly sales targets should also be monitored that add up to the yearly goal. Measuring performance is also a step that needs to be planned for during the first phase of the management process. How will I keep track once I begin my plan?

Monitoring performance might include creating a dashboard to monitor performance indicators, but it might also include periodic check in’s with members of the organization to see how they are handling the implementation of the plan. Step three simply means comparing the actual performance to standard. Step four is a reboot to the planning phase. In our sales analogy, let’s say that the yearly goal is a 14% improvement. By the fifth month, the sales manager checks the progress and sees that progress is slow, and they are only at 4%. The sales manager decides that to reach the goal, they recommit marketing resources to increase advertising. The progress was not up to the standard, so an adjustment is necessary. The flipside of step four is that even if progress is made towards goal, adjustments might still need to be made. Back to our sales analogy – five months in, and good progress is made. The sales team has done well, and the organization has made 9% towards the 14% goal. Even though progress is being made, a handful of salesmen are burnt out. The manager decides that the team could use a breather and decides to take all of the salesmen to an MLB baseball game, and dinner and wine to celebrate the small victory towards the goal. The salesmen are making progress, but they need an emotional break. The manager recognizes this and commits resources (organizing) to motivate (leading) the sales team to keep pushing. In this way, the control function cycles back to the other functions of management.

Timing of Control

We just reviewed that one of the main elements of control is to monitor progress and make adjustments. The second major component of the control process is to guide the progress. This guidance can happen at different times of the gameplan you are pursuing. Control mechanisms can be planned prior to implementation, during the implementation, and afterwards as a means to help future progress.

Feedforward control is putting in guiding rails prior to implementation of the gameplan. Bateman and Snell (2013) define this as a control process used before operations begin, including policies, procedures, and rules designed to ensure that planned activities are carried out properly. An example of a feedforward control mechanism is a manager who requires hard hats, harnesses, and safety protocols during the construction of an office building. These are policies that help ensure the gameplan will be carried out properly. This might also include a commitment to nets outside of scaffolding in addition to requiring harnessing for an office construction.

Concurrent control is a change you make during the implementation of the gameplan. In many ways, concurrent control is a mini version of the control process itself, done in a much shorter timeframe. This can include serious issues, like stopping production when you see a leak in the tank, to fine tuning that you might do as you are harvesting a field like adjusting the speed of the combine. In our road trip analogy, this is the slight turning of the wheel as the road curves, or completely taking a detour because your GPS says an accident is ahead. Reconciling real your budget real time as expenses come in is an example of concurrent control as you make small adjustments to spending as a result.

Feedback control uses information from previous results to make adjustments as you plan for future gameplans. This is the core of learning within an organization. This is the reason why NFL teams watch game film the day after a game. This means reviewing what you did well so you can keep doing it, to understanding where you failed and what caused it. Some organizations require a post mortem analysis for every major project they finish. What went wrong? How did we perform? The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010 that Foxconn installed safety nets outside of their Hebei, China factory after 10 employees jumped to their death. Reports indicate that employees live in dorms outside the plant in terrible conditions. This represents a feedback control process because their nets were an attempt to curb the death problem. This is a good example of feedback control, but not necessarily good management.

Types of Control

We have reviewed that control has a specific process to follow, and that process can be executed at several stages during the execution of the gameplan. What needs to be further explored are the types of control processes that managers have at their disposal. The basic definition of control is that we want to make sure we are on track and to guide the plan. Most control processes under this framework are formal mechanism, meaning management puts specific processes in place that everyone can see and track. These would include bureaucratic and market control processes. However, some control processes are considered informal, known as clan control.

Bureaucratic control is an official policy or rule implemented in the organization that is derived from the legitimate authority of the manager. Bureaucratic controls would include examples such as requiring daily reports on progress or inventory reconciliations. It could include establishing sales revenues projections, and implementing reward systems around this metric. It would include establishing protocols regarding the safety of heavy equipment operation or floor manufacturing at a factory. Many of these safety processes are established by governmental organizations such as OSHA or the EPA.

Market control is the use of external information to serve as a standard or metric against which to measure internal progress. Consider the following example. The marketing firm of an organization has designed a new product and the goal is to garner 15% market penetration in the first year. Prior to launching the product, they decide to bring in a consumer focus group to provide feedback on the design. This feedback compels the team to make some minor tweaks prior to product launch. This team has used an external element, that being the opinions of consumers, to make sure they progress towards their goal of a successful launch. Finance and trading organizations regularly used external controls around which to make decisions on which assets to divest, and in which assets to invest. This would include a trading strategy that establishes a standard that if the price of oil falls 25%, the company should liquidate their position in commodities to minimize losses.

Clan control consists of any form of informal influence that an organization has on an individual that directs them toward the goals of the organization. Clan control can derive from the cultural values and beliefs of the organization that influence behavior. Clan control can also be a more direct influence in the form of peer pressure. Consider the example of an organization that places high value on integrity. Jane is an accounting professional within the organization that refuses to violate a small section of the tax code in an area where the language of the tax code is gray. She decides to act on the conservative side and behave with integrity because she knows that her decision aligns with the personal values of her team leader, and if her integrity were questioned, she would be less esteemed by her peers. One final note on clan control is that it can wield either a positive or a negative influence on members of the organization.

Too Much Control?

There is a final aspect of the control process that needs to be explored. At what point does a manager put too many control mechanisms in place. There is a range of control mechanisms that can be used – too few and the manager would not be successfully monitoring or guiding progress, too many and the employees will feel like they are being micromanaged. Research shows that a manager that uses too few controls limits creativity, innovation, and organizational learning (Bligh, Kohles, & Yan, 2018). This makes sense if the manager’s main role is guiding the progress. Members of the organization don’t have the guidance and feedback that foster these ideals. A manager that puts too many control processes in place exposure the organization to lower levels of commitment, higher turnover, and more job stress among members of the organization (Bozeman, et al., 2001).

A manager has to appropriately balance the use of too much control and not enough control. If we return to Socrates and the Sordite’s Paradox, we can see that the extremes probably lead to negative outcomes. There is a gray area that managers might consider a reasonable level of control. Figure 8.2 shows this range of control.

Figure 8.2 A Range of Control

The balance between too much and too little is a complex one. More difficult yet, some employees might need more control, and others might need less control. Let’s explore that idea. On the right side of the control range, you might put more control mechanisms in place for employees who are new to the job. They are not experienced in the task that needs to be completed, so you need to monitor their performance so that you can give them feedback. The right side might include an employee who is engaged in a dangerous task such as operating heavy equipment, or flying an airplane. Think of all the checklists even experienced commercial pilots go through before turning on the aircraft. Each of these steps are control processes (lights and indicators showing avionics, mechanical performance, etc.). On the right side of the range might also include those who are making decisions with serious consequences such as profitability. For example, a company sending in a bid on a major project worth millions of dollars might have extra oversight to make sure the bid is done properly. The more serious the consequences, the more to the right on the control range the manager should consider. Finally, the right side of the control range should also be used when the task is brand new to the organization. Think about the response to 9/11, corona virus, or a mass shooting. How an organization responds to these events is one they have never experienced. Any strategy to deal with these situations might warrant more control processes to ensure its success. On the left side of the range you might put someone performing routine tasks or those that would result in low consequences if done incorrectly. On the left side would also include monitoring the performance of individuals who have proven themselves through previous performance. Monitoring their behavior or guiding their work would give them the feeling of micromanagement.

Critical Thinking Questions

What is the purpose of the control process?

In the discussion on feedback control, we reviewed the Foxconn response to employee suicides. This is clearly a feedback control mechanism but not good management. How can they use the control function of management differently to work on the heart of this problem?

How can you tell if you have put into place too much control?

How to Answer the Critical Thinking Questions

For each of these answers you should provide three elements.

- General Answer. Give a general response to what the question is asking, or make your argument to what the question is asking.

- Outside Resource. Provide a quotation from a source outside of this textbook. This can be an academic article, news story, or popular press. This should be something that supports your argument. Use the sandwich technique explained below and cite your source in APA in text and then a list of full text citations at the end of the homework assignment of all three sources used.

- Personal Story. Provide a personal story that illustrates the point as well. This should be a personal experience you had, and not a hypothetical. Talk about a time from your personal, professional, family, or school life. Use the sandwich technique for this as well, which is explained below.

Use the sandwich technique:

For the outside resource and the personal story you should use the sandwich technique. Good writing is not just about how to include these materials, but about how to make them flow into what you are saying and really support your argument. The sandwich technique allows us to do that. It goes like this:

Step 1: Provide a sentence that sets up your outside resource by answering who, what, when, or where this source is referring to.

Step 2: Provide the quoted material or story.

Step 3: Tell the reader why this is relevant to the argument you are making.

Chapter References

Bateman, T., & Snell, S. (2013). M: Management (3rd ed). McGraw Hill / Irwin: New York,

NY

Bozeman, D., Hochwarier, W., Perrewe, P., & Brymer, R. (2001). Organizational Politics,

Perceived Control, and Work Outcomes: Boundary Conditions on the Effects of Politics 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 486-503.

Bligh, M., Kohles, J., & Yan, Q. (2018). Leading and Learning to Change: The Role of

Leadership Style and Mindset in Error Learning and Organizational Change. Journal of Change Management, 18(2), 116-141.

Hagen, A., Udeh, I., & Wilkie, M. (2011). The Way That Companies Should Manage Their

Human Resources As Their Most Important Asset: Empirical Investigation. Journal of Business & Economics Research, 1(1).

Liberman, L. (2014). The impact of a Paternalistic Style of Management and Delegation of

Authority on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Chile and the US. Innovar, 24(53), 187-196.

Wall Street Journal (2010). Foxconn Installs Anti-jumping Nets at Hebei Plants. Retrieved from

https://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2010/08/03/foxconn-installs-antijumping-nets-at-hebei-plants/