5 Planning

Learning Objectives

The purpose of this chapter is to:

- 1) Introduce the components of the planning process

- 2) Identify the factors within the internal and external environments

- 3) Provide tools that are used in planning

Planning

Planning is the systematic process of making decisions about goals and activities the organization will pursue (Bateman & Snell, 2013). The planning function of management is often seen as the “first” step in managing. But, as we have reviewed in previous chapters, each of the management functions are inter-related and a comprehensive use of them as a portfolio of tools is necessary. Why would we focus on planning first. In simple terms, the planning process gives us focus and context for the other functions. Without the direction given by the planning phase, how would be know where to put our resources (organizing), or how to motivate people to work towards a common purpose (leading), or what we need to keep track of (controlling)?

Planning is the point in a manager’s day that they step away from their desk to think. This is the time that managers ask the proverbially question, “what do I want to be when you grow up?” By “I” they mean the organization, and by “grow up” they mean in the next quarter, year, or half decade. Planning requires foresight, and in some ways predicting the future. But the reality is that the future is unknown and unknowable, which means that planning is to venture into the unknown. As a result, planning is difficult and requires in many cases a flexible mindset to adjust to the constantly changing environment. So how do the best managers proceed? They begin first, with a solid analysis of the internal and external environment. They try to understand the internal culture and dynamics to take stock of the organization. They work to understand the external environment to understand where the opportunities and challenges exist in moving forward. This analysis gives managers a basis from which to establish a gameplan, and everything that flows from it – a mission to guide their organization, and goals to focus on.

Start with Analysis

Analysis is nothing more than identifying the elements of the context in which the organization exists. There are factors within the organization, which is part of the internal analysis, and there are factors that exist outside of the organization, which would be a part of the external analysis. Analyzing these components is done in a wide variety of ways, and is done with varying levels of accuracy and certitude. The internal components of the organization are much easier to analyze than the external factors (Crutchfield & Roughton, 2013), but can often times pose significant challenges to change. The external environment presents variables that are more difficult to analyze, but easier to navigate.

The purpose of the analysis is to identify where the opportunities and the challenges for the organization exist. An internal analysis focuses on the internal environment of organizational culture, history, capabilities, values, and resources. The internal analysis is done through cultural assessments, financial reporting, inventory requisitions, storytelling, or at a more basic level, a manager interacting with members of the organization. The external analysis accounts for any variable outside of the organization. This analysis focuses primarily on the competitive environment of the industry or space in which the organization operates such as consumers, suppliers, competitors, new entrants, and substitutes and complementary markets (Porter, 1980). The competitive environment presents risks and opportunities that are unique to a specific industry. The external analysis must also extend to identify the legal, technological, economic, political, demographic, and social elements that impact the organization at a macro level. These include pending and existing regulations, the availability of capital, new market and growth opportunities, prices, costs, labor force, education trends, impact of immigration, diversity, and consumer demand for products (Bateman & Snell, 2013).

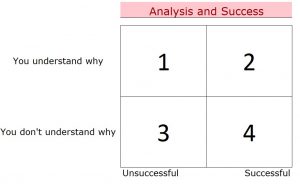

Analysis gives managers a bearing on where to create value. This means they take into account all of the opportunities, challenges, and risks that exist in each of these contexts, and then make a decision on which direction to guide the organization. Understanding the internal and external environments is key to increasing the probability of success. Consider the following grid in Figure 5.1. This grid represents outcomes whereby organizations are either successful or unsuccessful, and they understand what’s driving that particular outcome. Success can be defined by whatever the organization mission is: profits, market share, wins for a sports team, number of participants are an event, etc.

Figure 5.1 The four outcomes of analysis and success

In scenario #1, the organization is unsuccessful, but they have identified the variables that contributed to what went wrong. Here organizations have conducted an analysis and can make changes to their plan to improve in the future. Scenario #2 is ideal in that the organization is successful, and they understand exactly what contributed to their success. The only downside to this scenario is that success begets arrogance sometimes, and organizations sometimes have difficulty overcoming success with sustained levels of diligence and need for change (Hareli & Bernard, 2000) Consider the frustration of scenario #3, where the organization is unsuccessful and they have no clue as to why. Unless this organization works to understand their environment, they will not be around for long. Scenario #4 is perhaps the most dangerous of the scenarios where the organization is successful but they don’t know why. Maybe they got lucky, or maybe they are engaged in behaviors they don’t understand why its helping. In many cases, this scenario leads to arrogance, and unknown risks and unforeseen factors will later harm the organization.

Create a Gameplan

The analysis should give the organization a clear picture of where to proceed. What opportunities exist? What capabilities does the organization have to take advantage of those opportunities? Where are the dangers and how can we mitigate the risks? Porter (1980) established the standard for how to conduct a competitive strategy, and one of the main factors in his monolith on the subject was that once you have a direction, you need to orient every element of your organization towards that end. This means that the manager should give the organize purpose towards the identified end by establishing a mission or vision statement. As we will see in the organizing function, the people, technological, and financial resources must also be directed towards the organizational goals.

A good example of this analysis to gameplan connection is the case of Dominos turning around its organization (Taylor, 2016). They recognized that their market share was slipping because of poor delivery service, branding problems, and low quality of their pizzas. After conducting a thorough analysis of the market, they turned the organization around by embracing technology, amending their recipes, and taking to social media to rebrand the company. They have successfully regained market share and are today the second largest pizza delivery organization in the world.

We have already established that the managerial practice should be used in all organizations, not just the corporate board room. Consider the example of a high school basketball coach using the analysis and gameplan to help his team win. Coach Dave Martinson, or Boone High School in Orlando, Florida recognized that his team was outmatched heading into a game against national powerhouse Oak Ridge. His internal analysis of the talent, experience and motivation that his team possessed, le

d him to an unconventional and controversial gameplan. Because the opponent was faster, stronger, and more athletic, he had to limit the amount of times the opponent had the ball, and consequentially entered the game with the controversial “stall strategy.” High school basketball has no game clock which meant that he could strategically hold the ball for minutes at a time and when the other team was out of position, finally try to score. They won the game by drawing fouls and playing not their “best” players, but the players who could make free throws (Powers, 2019). Pundits on social media heavily criticized the coach’s decision, calling it unsportsmanlike and that he was telling his player’s they are “not good enough to compete” (para 5). The strategy came under fierce scrutiny, but it’s clear that the coach identified both the internal environment (his team’s talent) and the external factors (his opponent) to establish an effective gameplan.

Practical Tools Used in Planning

The rudimentary elements of planning are the analysis and gameplan. Both of these pillars have a wide flexibility on how to pursue them, and managers have a variety of tools to us in each stage. To gauge progress and to determine relative position, benchmarking is an effective tool for understanding industry best practices. Benchmarking entails comparing one organization’s practices, procedures or outcomes to those of the competition. It is an effective tool used during the analysis component of the planning phase. It provides managers with a starting place on where to set standards and goals for the organization.

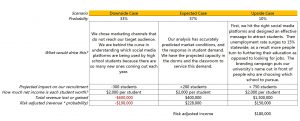

A second tool that managers use is the contingency plan. This tool is the response to the ambiguity that the external environment presents organizations. The contingency plan allows managers to account for the variations in outcomes that would result during the execution of a strategy. The contingency plan should include both the negative outcomes, expected case, as well as the upside scenarios where their gameplan proceeds better than planned. Contingency planning stems from the due diligence in the analysis component by asking “what if” during the gameplan design. “What if the market changes, what do we do?” “What if we exceed our target, do we have enough capacity to meet demand?” A planning tool that often couples the contingency planning is the risk adjusted decision making, whereby each of the projected scenarios is given a probability of happening, and the decision reflects the weighted consequences of those probabilities. Here’s an example of a basic risk adjusted decision making framework for a fictional university trying to increase enrollment for the following year. They must decide if they should launch a branding campaign that will cost them $100,000.

Figure 5.2 Risk adjusted decision making

In this scenario the manager projects the probability that the marketing campaign will be effective. These probabilities are based on analytics, or intuition, or historical numbers. The manager must identify which factors would determine the scenario and the financial impact it would have on revenues. Once these numbers are projected, the risk adjusted decision is to multiply the probabilities by the revenues to determine a project income. In this scenario, the downside scenario is that the campaign does not work, and the university loses students instead. This means that the university would lose $600,000 in revenues, but there is only a 33% chance of this happening, so the risk adjusted number is a loss of $198k. In the expected case and upside, the university would gain $228k + $150k using this same calculation. This results in a projected income of $180k (-$198k + $228k + $150k). The manager should spend the $100k to make an estimated $180k. It’s not important in an introductory management class that you master the financial details of the risk adjusted decision making models that corporations use, but it is important to recognize that the future is unknown, and good planning involves identifying scenarios and contingencies around your gameplan.

Once the environment is analyzed and a direction decided upon, the manager has to give the players within the organization a focus on this direction. This is done through use of a vision statement. Vision statements reiterate to the organization what purpose they serve, and the ends they pursue. Good vision statements are ones that allow members of the organization to recognize the moment when they get there. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr. stated that he could envision a day when “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers” (King, 1963). In this vision statement, you could see a day when children were playing with each other on a playground, holding hands. The ability to picture this outcome is what drove the civil rights movement. Effective vision statements allow followers to think about their role in contributing towards the outcomes and drives them towards the future. Consider, for example, a hospital establishing a vision that paints a picture for diagnostic staff, “imagine the moment that you recognize the problem that the client has struggled with, and not been able to identify. Picture the relief on their face as you tell them you know how to help.” This vision for a hospital should give medical staff a specific moment in time they will recognize when they get there. A coach creates the vision for his team, “Put yourself at the season opener of next year, when they are raising our championship banner from this year.” A best friend motivates you to get in shape by telling you “picture us walking out onto the balcony at the resort with our bathing suites on.” Vision statements are important for personal motivation, and for driving organizational direction. Consider Microsoft “a computer on every desk, and in every home.” This is an outcome employees can see happening at one point in the future.

Research conducted by Gulati, Mikhail, Morgan, and Sittig (2016) found that most vision statements are too generic to connect employees to the direction of the organization. For this reason, vision statements should elicit a specific moment, emotion, or place in the universe the members of the organization can picture themselves experiencing.

Smart goals are commonly used to improve the likelihood of the organization reaching its desired outcomes. Smart is an acronym that solidifies goal making by providing a framework. Smart stands for making goals Specific, Measureable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time constrained. Specific means that the goal should not be generic, and should list outcomes that are explicitly defined. Measurable means that the goal should be something quantifiable. You should be able to determine when you reach the goal based on its numeric nature. Achievable indicates the goal should be something the organization can collectively attain through sufficient, or improved effort. Stretching the organization beyond what they have done in the past to achieve more is desirable, but the goal should still be within the grasp of the organization or individual. Relevant simply means that the goal has to relate in some way to the purpose or identity of the organization. Time constrained implies that there should be a due date on the goal. Following this method for establishing organizational outcomes allows managers to quantifiably determine if the goal has been met. Research shows that being explicit with the desired outcomes, leads to stronger adherence to the goals by members, and improves the likelihood that they will be motivated to achieve them. The following two goals show the difference between a Smart goal, and a poorly written, more generic goal.

Goal #1 – Improve retail sales by 15% in the third quarter of this year.

Goal #2 – Be the industry leading manufacturer in service and quality

The first goal is one that meets all of the Smart criteria. At the end of the third quarter, the organization will be able to determine if they reached this goal or not. Ideally, all the employees would understand this goal and be incentivized to pursue it. The second goal is more generic goal, and a lot more difficult to determine when you get there. There are too many unanswered questions with this goal. How do we measure service and quality? How would we compare this to competitors to determine if we are number one?

Participatory planning is a method that managers use to include their team in the analysis and gameplanning of the organization. Research shows that involucration of team members improves the likelihood that they will buy into the direction of the organization. Research shows that participatory planning leads to higher levels of trust between managers and subordinates, increases commitment, builds loyalty, broadens thinking, and forms social capital within the organization (Menzel, Buchecker, & Schulz, 2013). As a result, many managers use this approach to broaden their alternatives, to increase organizational motivation, and to elicit ownership in the ideas created from the process.

Critical Thinking Questions

Describe the importance of the planning function.

Review the four outcomes in Figure 5.1. Category 2 is the best scenario, but which is the next best scenario to be in? Is it #1 where you are unsuccessful and you know why, or #2 where you are successful and you don’t know why?

Which of the practical tools described in the chapter is the most valuable for planning?

How to Answer the Critical Thinking Questions

For each of these answers you should provide three elements.

- General Answer. Give a general response to what the question is asking, or make your argument to what the question is asking.

- Outside Resource. Provide a quotation from a source outside of this textbook. This can be an academic article, news story, or popular press. This should be something that supports your argument. Use the sandwich technique explained below and cite your source in APA in text and then a list of full text citations at the end of the homework assignment of all three sources used.

- Personal Story. Provide a personal story that illustrates the point as well. This should be a personal experience you had, and not a hypothetical. Talk about a time from your personal, professional, family, or school life. Use the sandwich technique for this as well, which is explained below.

Use the sandwich technique:

For the outside resource and the personal story you should use the sandwich technique. Good writing is not just about how to include these materials, but about how to make them flow into what you are saying and really support your argument. The sandwich technique allows us to do that. It goes like this:

Step 1: Provide a sentence that sets up your outside resource by answering who, what, when, or where this source is referring to.

Step 2: Provide the quoted material or story.

Step 3: Tell the reader why this is relevant to the argument you are making.

Chapter References

Bateman, T., & Snell, S. (2013). M: Management (3rd ed). McGraw Hill / Irwin: New York,

NY

Crutchfield, N., & Roughton, J. (2013). Safety Culture : An Innovative Leadership Approach.

Elsevier Science & Technology, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central

Gulati, R., Mikhail, O., Morgan, R., & Sittig, D. (2016). Vision statement quality and

organizational performance in U.S. hospitals. Journal of Healthcare Management, 61(5), 335-350.

Hareli, S., & Weiner, B. (2000). Accounts for Success as Determinants of Perceived Arrogance

and Modesty. Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 215-236.

King, M. (1963). I have a dream. March on Washington, public address. Washington D.C.

Menzel, S., Buchecker, M., & Schulz, T. (2013). Forming social capital—Does participatory planning foster trust in institutions? Journal of Environmental Management, 131, 351-362.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors.

Simon and Schuster: New York, NY.

Powers, C. (2019). High school basketball team uses “stall offense” to win 20-16, gets

predictably roasted on Twitter. Yahoo Sports. Retrieved from https://sports.yahoo.com/high-school-basketball-team-uses-174914578.html