Learning Objectives

Understand the historical context of human resource development

Articulate the modern understanding and use of HR

Human Resources Simplified

If you are taking a class in Human Resource Management, there is a high likelihood that you have taken a handful of lower level management and sundry other business classes. What you might recognize from many of those earlier classes is the complexity of the concept explanations and vocabulary or processes that are described with technical vernacular and industry specific jargon. The intention of business schools is to educate students in the foundational concepts – like grasping the four functions of management (plan, lead, organize, control), or the basics of financial statements, or the 4 p’s of marketing. Yet despite what most courses list for learning objectives, the textbooks they choose are highly complex in nature, and the testing of material focuses on the technical components of the course. The purpose of this books is to remove the complexities that characterize not only management foundation courses, but in particular almost every HR textbook on the market today. The reality is that most students do not retain the technical components of their coursework, but rather find success in scaling up the foundational understandings and skillsets that they acquire in their undergraduate years.

Let’s look at some examples. Some textbooks use the term “voluntary turnover” instead of simply referring to when someone quits their job. Some textbooks refer to the Delphi technique as a method for brainstorming, or describe in detail the rules regarding prima facie cases of the EEOC. If you ask yourself the reason why textbooks include all of these technical aspects of HR, the answer can likely be found in how professors approach their work. In academic publishing, professors are often looking for new ways to coin terms so that other authors will cite their work and hence improve their status as researchers. For this reason, they come up with words like intrapreneurship, and voluntary turnover to describe concepts that we can grasp in more simple terms otherwise. In their defense, the reason that HR textbook authors include a long variety of complex terminology is to provide flexibility for professors who use the book. Instructors can pick and choose the chapters and concepts to cover, and can make their courses as simple or complex as they would like to.

The truth is that if you become an HR professional, or you find yourself in a management role that works closely with HR, you will become proficient in the technical aspects of human resources. For now, this book should provide you with a foundation so that you know the depth, scope, and purview of what HR managers do. This will equip you to know which questions to ask, or where to find resources, when the time comes to involve HR in your decisions as a manager.

You can thank whichever professor assigned you this textbook for the HR class you are taking. First, its free of charge to you (who doesn’t love that), and second, the concepts are explained with simplicity and directness.

Four Eras of HR

If you are a fan of the Chicago Cubs, you probably spent most of your fandom in misery and torture. That is, until they won the world series in 2016, ending a 110 year championship drought. If you stuck with the Cubs your whole life, you had to endure decades of not even making the playoffs, watching your hopes grow and die with the addition of not one but two aces (Price and Woods) who subsequently got hurt. Seven losses in the World Series since their last championship, and of course, the infamous scene in the 2003 playoffs whereby Steve Bartman interfered with Moises Alou’s ability to field a fly ball. The heartbreak of all these years made the success of the 2016 World Series sweeter, and more indulgent. Bandwagon fans were oblivious or impervious to the emotional rollercoaster that had been the previous century. They did not experience the lows, and therefore the highs were capped at the bandwagon, temporary excitement level. What’s the point of all this? Its important to understand the history of whatever organization, field, industry, or country so that 1) on a practical level mistakes are not repeated and 2) you can reflect on the progression from early years and appreciate the current state of affairs. Human Resources is no different. Today we enjoy an immense array of employee focused benefits which allow the employee the latitude and flexibility to develop into a better contributor. Personal rights are protected at most levels, and organizations themselves are taking measures well above legal minimums to engage their labor team in meaningful ways. This was not always the case. The U.S. has a long history of labor practices, but many of them were characterized by compulsory practices, limited mobility, organization favored laws, and inequalities between classes.

A comprehensive history of human resources in the United States was classified into four distinct eras by Langbert and Friedman (2002) as the Pre-Industrial period, the Paternalist period, the Bureaucratic period, and the High-Performance period. Their coverage of history includes the progression of legitimate practices such as apprenticeships, factory conditions, and employee motivational strategies as well as the illegitimate and unethical labor practices such as slavery, limited mobility, organization favored laws, inequalities between classes, and abhorrent conditions of the industrial revolution. The purpose of this chapter is to give you an overview of the history of HR in the United States so that you have a better understanding of the context of modern practices.

Bert was recently moved into a new role for the dental equipment company that he worked for. His new job would require him to prospect new clients internationally. After conducting a thorough market analysis, he concluded that market potential lied in western Europe and the west Africa region. As part of his training he was shown how to develop relationships, advance the sales process, and gain referrals. However, something about his attempts in these regions fell flat. Bert concluded that he needed to really understand the culture and the language if he was going to build significant customer relationships. Despite the downward trend in revenues and profits, the company decided to invest in Bert’s language skills. He promptly enrolled in both French and German classes, hired private tutors, paid for premium software packages, and spent work hours acquiring the language. All of these resources were provided by his company as a means to developing Bert, a modern HR practice of developing the individual that results in both benefits to the company and expanded skillsets for employees. Bert gained a business level proficiency in both French and German, and his sales figures in these regions flourished. This contribution by the employer towards Bert’s development is a reflection of modern practice whereby organizations are contributing to individuals as an ends to itself. This HR practice is only a recent phenomena and is the culmination of many centuries of labor practice which would have seen this as unthinkable for an employer to do.

The Four Eras of Human Resources in the United States

In the United States we characterize the management of people under the general umbrella of human resource management. However, the United States is only two and a half centuries old, and labor practices (how organizations within a society treat workers) have been around since the beginning of human work. The purpose of this chapter is to start at the beginning of the American story and provide an annotated summary of each of the major eras, culminating in modern practice. The following eras in HR practice were characterized by Langert & Friedman (2002), which are further developments of work by Jacoby (1985) – the pre-industrial period, the paternalist period, the bureaucratic period, and the high performance period. They argue that as these eras were progressions of labor practice that stabilized the modern practice of HR – beginning with the barbarous practices of compelled labor (slavery and indentured servitude) in the pre-industrial period to the efficiency and value creation that the high-performance period affords the modern organization.

The Pre-industrial Period (1600-1780)

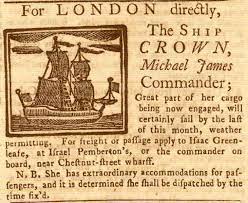

Before the United States became a country in 1776, there was a long history of labor practices that were employed throughout most of the colonized world. Demand in Europe was high for the bounty and goods that the colonies afforded their French, English, Dutch, Portuguese, and Danish patriarchs. Yet, extracting, processing, and transporting the goods back to Europe presented a unique problem – there was not enough labor to do the work. The European powers resorted to a handful of strategies to fill the gap – both slavery and indentured servitude (Wareing, 2017).

At the same time European powers were supplying the growth of their colonies in the west with slaves from Africa and South America, kingdoms from the Middle East were buying or stealing slaves to take east from Africa. Tribes within Africa regularly utilized slaves from neighboring tribes they conquered during times of war. Natives in North and South America adopted similar practices. To say the least, slavery was regularly practiced around the world by Europeans and non-Europeans alike during this time.

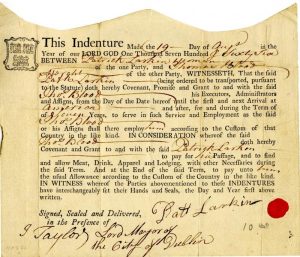

In addition to slavery, European countries supplied more labor using their homeland populations by means of indentured servitude. The growth of tobacco, rice, and indigo within the plantation economy created a tremendous need for labor in the Southern English America. The arrangement for an indentured servitude was codified in the form of a contract. Picture an English citizen within the working class with little in terms of assets (money, land, etc) or prospects.

As a way to get passage on a ship bound for the American colonies, he signs away four to seven years of his life as a means to pay. Upon arrival to an eastern port, the ship’s captain would walk down to the wharf and sell the contracts of the contracted labor. After the obligation was completed years later, the servant would be granted their freedom and in some situations would be granted 25 acres of land, a year’s worth of corn, arms, livestock, and new clothes. Once indentured servants completed their term, they became members of the social structure, fueling more growth, capacity and demand. “The man who labored for another last year this year labors for himself and next year he will hire others to labor for him” (Foner, 1995, p. 30).

Unlike slavery where the individual was bought or sold, under indentured servitude, contracts could be bought and sold, but not people. African slaves were initially brought to the American colonies in Jamestown, VA in 1619. Some scholars speculate that slaves were initially treated as indentured servants alongside their white, European counterparts (Smithsonian, 2021)

Slavery was governed by the slave codes implemented by each state. These codes varied in both scope and enforcement. Some examples of the slave codes (Slave Codes, 2014):

- Ø Owners refusing to abide by the slave code are fined and forfeit ownership of their slaves.

- Ø No slave is allowed to work for pay; plant corn, peas or rice; keep hogs, cattle, or horses; own or operate a boat; buy or sell; to wear clothes finer than ‘Negro cloth.’

- Ø No slave is to be taught to write, to work on Sunday, or to work more than 15 hours per day in summer, and 14 hours in winter.

- Ø The fine for concealing runaway slaves is $1,000 and a prison sentence of up to one year.

- Ø In Florida, a slave charged with a capital offense was entitled to legal counsel to represent him on the theory that the master should not be deprived of his property by hanging unless the slave got a fair trial.

This era called the Pre-industrial period is characterized by the immorality of slavery and the poor conditions of indentured life. This period was sustained with poor working conditions, limited compensation (indentured servitude) or no compensation (slavery). Workplace benefits included housing, food, and clothes for slaves, and compensation for indentured servants included some rewards upon completion of a contract. Labors out of compliance with the requirements of the plantations and other employers could be handled with death, physical restraint, incarceration, and state enforcement.

Finally, the Pre-industrial period held another form of labor that contains vestigial elements of modern labor practices. Apprenticeships were a common method of creating new supply of labor within communities. An apprenticeship would comprise of a binding contract between a novice and a master craftsman. The apprentice would learn the craft of silversmithing, coopering (barrel making), cobbling (shoemaking and repair), blacksmithing, haberdashery (men’s clothing sales), tailoring, and the various trades practiced throughout the American colonies. As part of the contract, apprentices agreed to keep trade secrets, obtain permission to leave the premises of the master, abstain from vices such as drinking, gambling and the theater. In exchange for learning the craft of the master tradesman, the apprentice worked without wages for the duration of the contract period. Masters would provide training of the craft first and foremost, but were also charged with educating the apprentice in the basics of reading, writing, and mathematics. Apprentices received room and board, and on occasion a set of tools they could use once they completed the contract. Laws in the northern colonies obligated organizations to place orphans as apprentices wherever it was possible. Upon completion of the training, apprentices would begin the next stage known as journeyman, whereby they would work for wages. After years of honing their skills, they would become a master craftsman and begin to take on apprentices of their own.

The Paternalist Period (1780-1920)

By the end of the Pre-Industrial period, the United States had won their freedom from England. The invention of the steam engine allowed for unimagined advances in use of mechanical advantage. Factories were built around this new ability to move heavy objects, bend metals, and create immense force on objects as a means of production. The assembly lined allowed for mass production of clothing, machinery, processed goods, and component parts. Perhaps more impactful was the publication of Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith – which promulgated the tenets of free market thinking and exchange of goods between countries and production regions.

As a result of these factors, industry was burgeoning in the developing world as workers flocked from the agrarian communities in Europe to city centers. The same was true within the Northern region of the U.S. During the Paternalist period, labor was seen as a factor of production and modifications to human resource practices reflected management’s desire to increase overall production.

Working conditions were often atrocious as owners of the factories exploited the newly hired labor. Workers were housed in small dormitories with cramped conditions. Workers were exposed to on the job risks and safety was a low priority for factory owners. This included cramped working areas, inadequate ventilation from the fumes of the machinery, injuries from the machines themselves, and exposure to toxic chemicals and metals. These conditions speak to the physical conditions of the industrial revolution, but the emotional and psychological hazards of working consistently in these conditions were immense as well. Long hours, limited sustenance, and impersonal treatment contributed to an already stressful work environment.

During the course of the Paternalist period, slavery was abolished in the United States, and indentured servitude became an out of date practice. Several labor laws and court rulings changed human labor practices in the United States. This era, for example saw the advent of employment-at-will, whereby employment terms were no longer always subject to contractual arrangements, but day-by-day agreements between suppliers (workers) and consumers (factory owners, farmers, etc). In Payne v. Western & Atlantic Railroad Co (1884) the courts determined that “all [companies] may dismiss their employees at will, be they many or few, for good cause, for no cause, or even for cause morally wrong, without being thereby guilty of legal wrong.”

Towards the latter part of the period, the concept of incentive compensation was introduced. Workers were paid extra wages and benefits for reaching specific output goals of the organization. Although the intention of incentive compensation was to motivate workers to produce more, the result was less than what factory owners were hoping for. Whiting Williams, a management scholar and practitioner operating in the early 1900s went “undercover” to discover what was happening at the factory floor level. He wrote a book entitled “What’s on the Worker’s Mind: By One Who Put on Overalls to Find out.” He discovered that workers did not increase production despite the incentives for several reasons. Earning more money would not have changed their social class, and neither did the workers hope it would. Workers held their professions and identities in the communities in which they lived. Moreover, they partook in what Whiting termed “soldiering” whereby workers agreed on an output level well below the maximum level for fear that management would see what they were truly capable of and increase daily expectations. Those lone, ambitious individual workers who tried to reach the incentive levels on their own were quickly chastised and hazed by the mass of workers who did not want to see production go up. Frederick Taylor, considered by most scholars as the father of modern management had similar observations of the workers’ mentality at the time. “Hardly a competent workman can be found who does not devote a considerable amount of time to studying just how slowly he can work and still convince his employer that he is going at a good pace.”

The Bureaucratic Period (1920-1970)

The Bureaucratic Period placed great emphasis on rules and procedures in the workplace. These rules were in place to control workers, stymie creativity, and elicit compliance with the prescribed method of operations. Owners of companies had money and education, and they determined which practices should be followed. There was limited solicitation from the uneducated workforce actually performing the tasks of every life in an organization. During this era, labor was still seen as a factor of production, and managers’ jobs were to find ways to maximize the physical efforts of laborers. Limited attention was given to the emotional, psychological, or social well being of the labor force. These motivational factors were considered outside the scope of management, and the expectation was that workers would come to the life of the company fully motivated. During the Bureaucratic Period much progress was made in the realm of Human Resource practices. These changes came as a result of laws and court decisions that guided. It was during this era that we begin to see the framework of modern HR practice.

Many laws that apply to work environments today were passed during this time. The Wagner Act (1935) was the first of its kind. It gave workers the right to assemble as a union to fight the oppressive tendencies of organizations. This formed the National Labor Relations Board as an adjudicating body to hear cases that violated the workers’ right to unionize. Over the course of the next forty years, union membership would grow to the highest in recorded U.S. history, and workplace conditions improved as a result. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act which set minimum wage levels, overtime pay, required more diligent record keeping, addressed workplace conditions, and banned child labor. By the mid 1960s the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing, and as a result the Civil Rights Act (1964) established rules for fair workplace practices. This piece of legislation banned discrimination in hiring, firing, promoting, and harassing of anyone based on their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It took many years for the courts and workplaces to understood what this meant for the everyday life of the worker, but the Civil Rights Act established the rules for modern HR practices on the fair treatment of workers.

Finally, while the professional world was reacting to the legislation and court cases guiding workplace practice, the academic world was busy discovering what really motivated workers. During the 1950s and 1960s researchers put forth several theories as to what motivated the worker. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Vroom’s expectancy theory, Alderfer’s ERG (Existence, Related, Growth) theory, McClelland’s theory of needs (achievement, affiliation, or power), Herzberg’s two-factor they, and Adam’s equity theory all came to the forefront during this time. Scholars were discovering that worker’s motivation was related to their social and emotional health, as well as their needs for relation, comparison, compensation, recognition, and much more. These factors would regulate their output on a production floor if the needs were not met. The impetus for the discovery of the human being as a social animal during this time actually started in the 1920s and 1930s. Elton Mayo begin to discover elements that predated the prominent motivational theories that were to come. The Hawthorne studies in Chicago was an enlightening moment during the 1940s as researchers discovered that the social elements of the workplace could impact production levels. The work of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth as well as Mary Follett uncovered human elements of the workplace long before Maslow published his work (considered the first motivational theory during the 1950s).

In the aftermath of the social movement of the 1950s as well as the civil rights movement of the 1960s, organizations began to transition from a focus on workers as a factor of production to a humanistic view of their workforce. They began to realize the immense power that employees held if they were properly treated, incentivized and included. The conclusion of the Bureaucratic Movement ushered in the High Performance Period that characterizes modern HR practices.

The High Performance Period (1970-present day)

The enlightening findings at the end of the Bureaucratic Period led companies to rethink how they treated employees. They understood that employees could be motivated given the right workplace conditions, and that employees could contribute to the organization in ways beyond simple production. Workers for generations had untapped sources of creativity, energy, ingenuity, complimentary talents and pride in their work. The High Performance Period saw the advent of many workplace practices that attempted to pull this value out of their workers. Ultimately, the human resource practices culminate in human resource development – whereby workers and the organization as a whole are in a continual learning cycle and change management mentality so that they can adapt to the changes the market and competitors throw at them.

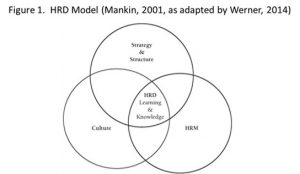

In this era, management practices focus on both empowerment (giving workers autonomy over their work) as well as delegation (giving them tasks to compete). The emphasis on employees as motivational beings resulted in increased morale and engagement. The workforce as a result focused on customers and overall service improved. The concepts of individual and group motivation are now given explicit consideration in human resources, and organizational citizenship behaviors are encouraged and rewarded. Ultimately, HR has been pulled in as strategic partner in the organization (Villegas & Yamamoto, 2020) with a seat at the table with their finance and operational executive peers. Human resource development is a combination of human resource practices, organizational culture, and the overall strategy of the organization. The practices that characterize HR development are called high performance work systems where the individual is provided with a work environment designed to maximize their overall potential and create the most value for the organization. We will cover this era in more detail in the final two chapters of the book.

How this book is organized

The rest of this book will detail the elements of modern labor practices in the United States. Chapter 2 will describe the inexorable link between human resource practices and the laws and regulations guiding them. Chapter 3 will provide an overview of the modern HR practices of talent acquisition, total rewards, diversity and inclusion, U.S. employment laws, technology and data, employee relations, employee engagement, organizational effectiveness and development, learning and development, HR structure, HR strategy, risk management, global context, and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Chapter 4 will provide an in-depth summary of the practice of High Performance Work Systems (HPWS) and finally Chapter 5 will conclude the text with how modern practice culminates in Human Resource Development.

- Explain why understanding the history of something helps you better practice it.

- The U.S. has some dark parts of its labor history, how has this affected modern labor practices?