10.1 What is Conflict?

The word “conflict” produces a sense of anxiety for many people, but it is part of the human experience. Just because conflict is universal does not mean that we cannot improve how we handle disagreements, misunderstandings, and struggles to understand or make ourselves understood. Joyce Hocker and William Wilmot (1991) offer us several principles on conflict that have been adapted here for our discussion:

- Conflict is universal.

- Conflict is associated with incompatible goals.

- Conflict is associated with scarce resources.

- Conflict is associated with interference.

- Conflict is not a sign of a poor relationship.

- Conflict cannot be avoided.

- Conflict cannot always be resolved.

- Conflict is not always bad.

Conflict is the physical or psychological struggle associated with the perception of opposing or incompatible goals, desires, demands, wants, or needs (McLean, S., 2005). When incompatible goals, scarce resources, or interference are present, conflict is a typical result, but it does not mean the relationship is poor or failing. All relationships progress through times of conflict and collaboration. How we navigate and negotiate these challenges influences, reinforces, or destroys the relationship. Conflict is universal, but how and when it occurs is open to influence and interpretation. Rather than viewing conflict from a negative frame of reference, view it as an opportunity for clarification, growth, and even reinforcement of the relationship.

Types of Conflict in the Workplace

Interpersonal Conflict

Interpersonal conflict is among individuals such as coworkers, a manager and an employee, or CEOs and their staff. For example, in 2006 the CEO of Airbus S.A.S., Christian Streiff, resigned because of his conflict with the board of directors over issues such as how to restructure the company (Michaels, Power, & Gauthier-Villars, 2006). Airbus CEO’s resignation reflects the company’s deep structural woes. This example may reflect a well-known trend among CEOs. According to one estimate, 31.9% of CEOs resigned from their jobs because they had conflict with the board of directors (Whitehouse, 2008). CEOs of competing companies might also have public conflicts. In 1997, Michael Dell was asked what he would do about Apple Computer. “What would I do? I’d shut it down and give the money back to shareholders.” Ten years later, Steve Jobs, the CEO of Apple Inc., indicated he had clearly held a grudge as he shot back at Dell in an e-mail to his employees, stating, “Team, it turned out Michael Dell wasn’t perfect in predicting the future. Based on today’s stock market close, Apple is worth more than Dell” (Haddad, 2001). In part, their long-time disagreements stem from their differences. Interpersonal conflict often arises because of competition, as the Dell/Apple example shows, or because of personality or values differences. For example, one person’s style may be to “go with the gut” on decisions, while another person wants to make decisions based on facts. Those differences will lead to conflict if the individuals reach different conclusions. Many companies suffer because of interpersonal conflicts. Keeping conflicts centered around ideas rather than individual differences is important in avoiding conflict escalation.

Intergroup Conflict

Intergroup conflict is conflict that takes place among different groups. Types of groups may include different departments or divisions in a company, an employee union and management, or competing companies that supply the same customers. Departments may conflict over budget allocations; unions and management may disagree over work rules; suppliers may conflict with each other on the quality of parts. Merging two groups together can lead to friction between the groups—especially if there are scarce resources to be divided among the group. For example, in what has been called “the most difficult and hard-fought labor issue in an airline merger,” Canadian Air and Air Canada pilots were locked into years of personal and legal conflict when the two airlines’ seniority lists were combined following the merger (Stoykewych, 2003). Seniority is a valuable and scarce resource for pilots, because it helps to determine who flies the newest and biggest planes, who receives the best flight routes, and who is paid the most. In response to the loss of seniority, former Canadian Air pilots picketed at shareholder meetings, threatened to call in sick, and had ongoing conflicts with pilots from Air Canada. The conflicts with pilots continue to this day. The history of past conflicts among organizations and employees makes new deals challenging.

Is Conflict Always Bad?

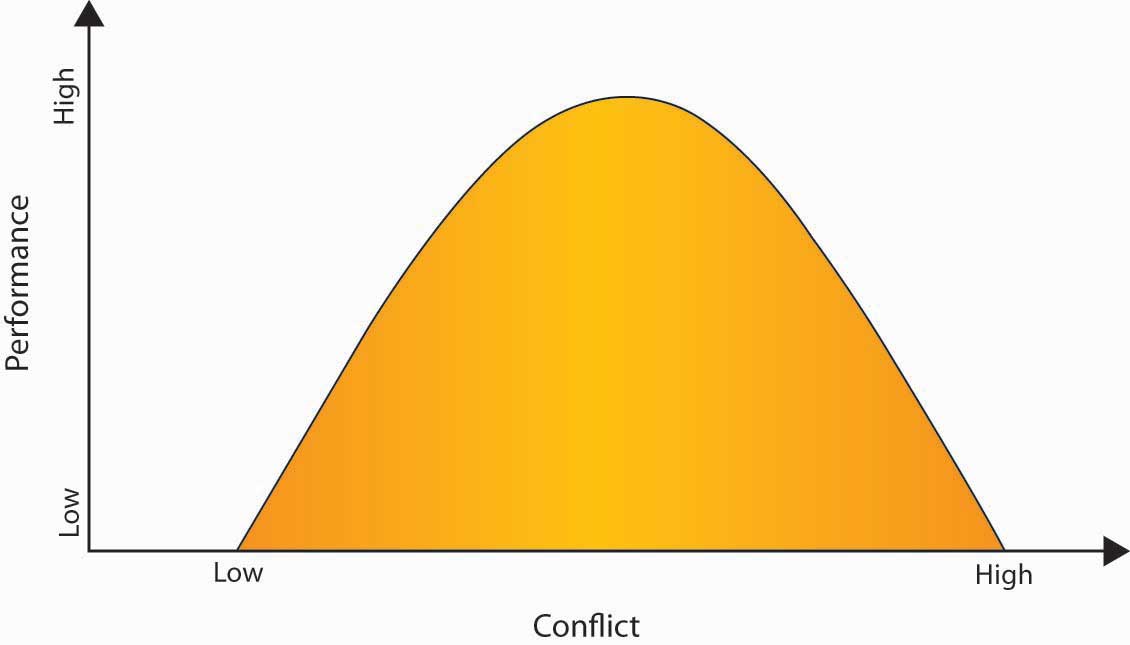

Most people are uncomfortable with conflict, but is conflict always bad? Conflict can be dysfunctional if it paralyzes an organization, leads to less than optimal performance, or, in the worst case, leads to workplace violence. Surprisingly, a moderate amount of conflict can actually be a healthy (and necessary) part of organizational life (Amason, 1996). To understand how to get to a positive level of conflict, we need to understand its root causes, consequences, and tools to help manage it. The impact of too much or too little conflict can disrupt performance. If conflict is too low, then performance is low. If conflict is too high, then performance also tends to be low. The goal is to hold conflict levels in the middle of this range. While it might seem strange to want a particular level of conflict, a medium level of task-related conflict is often viewed as optimal, because it represents a situation in which a healthy debate of ideas takes place.

Figure 10.1 The Inverted U Relationship Between Performance and Conflict

Task conflict can be good in certain circumstances, such as in the early stages of decision-making, because it stimulates creativity. However, it can interfere with complex tasks in the long run (De Dreu, & Weingart, 2003). Personal conflicts, such as personal attacks, are never healthy because they cause stress and distress, which undermines performance. The worst cases of personal conflicts can lead to workplace bullying. At Intel Corporation, all new employees go through a 4-hour training module to learn “constructive confrontation.” The content of the training program includes dealing with others in a positive manner, using facts rather than opinion to persuade others, and focusing on the problem at hand rather than the people involved. “We don’t spend time being defensive or taking things personally. We cut through all of that and get to the issues,” notes a trainer from Intel University (Dahle, 2001). The success of the training remains unclear, but the presence of this program indicates that Intel understands the potentially positive effect of a moderate level of conflict. Research focusing on effective teams across time found that they were characterized by low but increasing levels of process conflict (how do we get things done?), low levels of relationship conflict with a rise toward the end of the project (personal disagreements among team members), and moderate levels of task conflict in the middle of the task timeline (Jehn, & Mannix, 2001).

Key Takeaway

Conflict is unavoidable and can be an opportunity for clarification, growth, and even reinforcement of the relationship. Conflict can be a problem for individuals and organizations. There are several different types of conflict, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, and intergroup conflict. Moderate conflict can be a healthy and necessary part of organizational life.