7.7 Movement and Vocal Qualities in Your Presentation

[Author removed at request of original publisher]; Linda Macdonald; and Saylor Academy

At some point in your business career, you will be called upon to give a presentation or remarks. It may be to an audience of one on a sales floor or to a large audience at a national meeting. You already know you need to make a positive first impression, but do you know how to use movement and vocal qualities to the most powerful effect in your presentation? In this section, we will examine several strategies for using movement and voice.

Customers and audiences respond well to speakers who are comfortable with themselves. Comfortable does not mean overconfident or cocky, and it does not mean shy or timid. It means that an audience is far more likely to forgive the occasional “umm” or “ahh,” or the nonverbal equivalent of a misstep if the speaker is comfortable with themselves and their message.

Movement

Let us start with behaviors to avoid. Would you rather listen to a speaker who moves confidently across the stage or one who hides behind the podium, one who expresses themselves nonverbally with purpose and meaning or one who crosses their arms or clings to the lectern?

Audiences are most likely to respond positively to open, dynamic speakers who convey the feeling of being at ease with their bodies. The setting, combined with audience expectations, will give a range of movement. If you are speaking at a formal event, or if you are being covered by a stationary camera, you may be expected to stay in one spot. If the stage allows you to explore, closing the distance between yourself and your audience may prove effective. Rather than focus on a list of behaviors and their relationship to environment and context, give emphasis to what your audience expects and what you yourself would find more engaging instead.

Novice speakers are sometimes told to keep their arms at their sides or to restrict their movement to only that which is absolutely necessary. If you are in formal training for a military presentation, or a speech and debate competition, this may hold true. But in business and industry, expressive gestures, like arm movements while speaking, may be appropriate and, in fact, expected.

The questions are, again, what does your audience consider appropriate and what do you feel comfortable doing during your presentation? Since the emphasis is always on meeting the needs of the customer, whether it is an audience of one on a sales floor or a large national gathering, you may need to stretch outside your comfort zone. On that same note, do not stretch too far and move yourself into the uncomfortable range. Finding balance is a challenge, but no one ever said giving a speech was easy.

Movement is an important aspect of your speech and requires planning, the same as the words you choose and the visual aids you design. Be natural, but do not naturally shuffle your feet, pace back and forth, or rock on your heels through your entire speech. These behaviors distract your audience from your message and can communicate nervousness, undermining your credibility.

Positions on the Stage

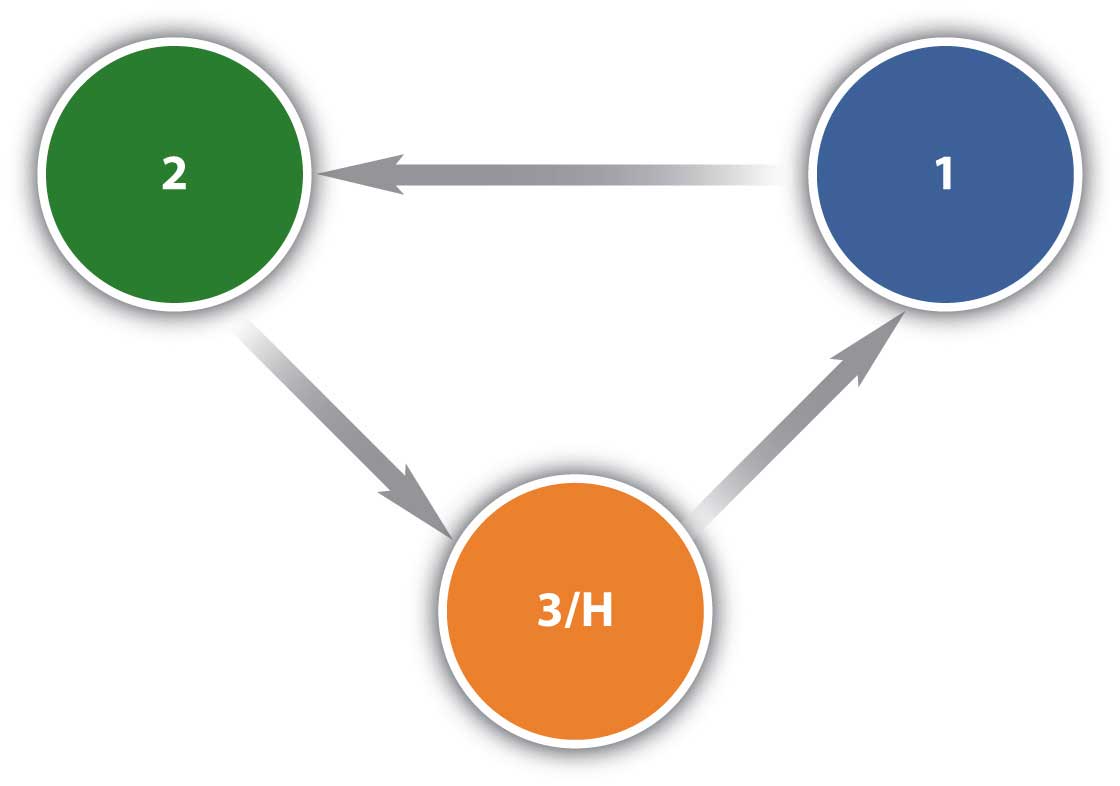

In a speech presentation, positions on the stage can guide both the speaker and the audience through transitions. The speaker’s triangle (see Figure 7.2) indicates where the speaker starts in the introduction, moves to the second position for the first point, across for the second point, then returns to the original position to make the third point and conclusion. Movements from one point to another should align with verbal transitions. This movement technique can be quite effective to help you remember each of your main points. It allows you to break down your speech into manageable parts. Your movement will demonstrate purpose and reinforce your credibility and can help an audience follow your presentation.

Gestures

Gestures involve using your arms and hands while communicating. Gestures provide a way to channel your nervous energy into a positive activity that benefits your speech and gives you something to do with your hands. For example, watch people in normal, everyday conversations. They frequently use their hands to express themselves. Do you think they think about how they use their hands? Most people do not. Their arm and hand gestures come naturally as part of their expression, often reflecting what they have learned within their community.

For professional speakers, this is also true, but deliberate movement can reinforce, repeat, and even regulate an audience’s response to their verbal and nonverbal messages. You want to come across as comfortable and natural, and your use of your arms and hands contributes to your presentation. A well-chosen gesture can help make a point memorable or lead the audience to the next point.

Facial Gestures

As you progress as a speaker from gestures and movement, you will need to turn your attention to facial gestures and expressions. Facial gestures involve using your face to display feelings and attitudes nonverbally. They may reinforce, or contradict, the spoken word, and their impact cannot be underestimated. People often focus more on how we say something than what we actually say, and place more importance on our nonverbal gestures (Mehrabian, 1981). As in other body movements, your facial gestures should come naturally, but giving them due thought and consideration can keep you aware of how you are communicating the nonverbal message.

Facial gestures should reflect the tone and emotion of your verbal communication. If you are using humor in your speech, you will likely smile and wink to complement the amusement expressed in your words. Smiling will be much less appropriate if your presentation involves a serious subject such as cancer or car accidents. Consider how you want your audience to feel in response to your message, and identify the facial gestures you can use to promote those feelings. Then practice in front of a mirror so that the gestures come naturally.

In Western cultures, eye contact is essential for building a relationship with the audience. Eye contact refers to the speaker’s gaze in engaging the audience members. It can vary in degree and length, and in many cases, is culturally influenced. Both the speaker’s and audience members’ notions of what is appropriate will influence normative expectations for eye contact. In some cultures, there are understood behavioral expectations for male gaze directed toward females, and vice versa. In a similar way, children may have expectations of when to look their elders in the eye and when to gaze down. Depending on the culture, both may be nonverbal signals of listening. Understanding your audience is critical when it comes to nonverbal expectations.

When giving a presentation, avoid looking over people’s heads, staring at a point on the wall, or letting your eyes dart all over the place. The audience will find these mannerisms unnerving. They will not feel as connected, or receptive, to your message and you will reduce your effectiveness. Move your eyes gradually and naturally across the audience, both close to you and toward the back of the room. Try to look for faces that look interested and engaged in your message. Do not focus on only one or two audience members, as audiences may respond negatively to perceived favoritism. Instead, try to give as much eye contact as possible across the audience. Keep it natural, but give it deliberate thought.

Voice

In “Your Speaking Voice”, Toastmasters International (2011) says that “you can develop the sort of voice that wins favorable attention and reflects the qualities you wish to project” (p. 3). According to Toastmasters, you can correct bad speaking habits and develop effective speaking qualities by aiming to develop a voice that is

-

pleasant, conveying a sense of warmth

-

natural, reflecting your true personality and sincerity

-

dynamic, giving the impression of force and strength – even when it is not especially loud

-

expressive, portraying various shades of meaning and never sounding monotonous or without emotion

-

easily heard, thanks to proper volume and clear articulation (Toastmasters International, 2011)

In working to convey a sense of warmth, remember that your goal is to build a relationship with your audience. In most business settings, a conversational tone is appropriate for achieving a connection. Toastmasters’ second goal concerns a natural, genuine personality. Speaking from your core values helps achieve this goal.

A dynamic and expressive voice uses a range of volumes, pace, and inflections to enhance the content of the presentation. Toastmasters says that an effective speaker may use as many as 25 different notes: “A one-note speaker is tedious to an audience and promotes inattention and boredom. Vocal variety is the way you use your voice to create interest, excitement, and emotional involvement. It is accomplished by varying your pitch, volume, and timing” (p. 6). A dynamic voice is one that attracts attention and reflects confidence.

Filler words like “um” and “uh” can reduce your dynamism and affect your credibility since you may appear unsure or unfamiliar with your content. In addition to avoiding this filler-word habit, avoid using a “vocal fry“, a low growl at the end of a sentence, or an uplift at the end of a declarative statement. The effects of these habits on your demonstration of authority and conviction are addressed in this three-minute video by Taylor Mali:

(Direct link to Totally like whatever, you know by Taylor Mali video)

Resonance

One quality of a good speaking voice is resonance, meaning strength, depth, and force. This word is related to the word resonate. Resonant speech begins at the speaker’s vocal cords and resonates throughout the upper body. The speaker does not simply use his or her mouth to form words, but instead projects from the lungs and chest. (That is why having a cold can make it hard to speak clearly.)

Some people happen to have powerful, resonant voices. But even if your voice is naturally softer or higher pitched, you can improve it with practice.

- Take a few deep breaths before you begin rehearsing.

- Hum a few times, gradually lowering the pitch so that you feel the vibration not only in your throat but also in your chest and diaphragm.

- Try to be conscious of that vibration and of your breathing while you speak. You may not feel the vibration as intensely, but you should feel your speech resonate in your upper body, and you should feel as though you are breathing easily.

- Keep practicing until it feels natural.

Enunciation

Enunciation refers to how clearly you articulate words while speaking. Try to pronounce words as clearly and accurately as you can, enunciating each syllable. Avoid mumbling or slurring words. As you rehearse your presentation, practice speaking a little more slowly and deliberately. Ask someone you know to give you feedback.

Volume

Volume is simply how loudly or softly you speak. Shyness, nervousness, or overenthusiasm can cause people to speak too softly or too loudly, which may make the audience feel frustrated or put off. Your volume should make the audience comfortable– not so soft that audiences must strain to hear you or so loud that audiences feel threatened or uneasy. You will need to adjust your volume depending on the size of your audience and the space to ensure that the person farthest away from you can hear. You may also need to eliminate outside noises by closing doors and windows. Be sure that you do not create noises yourself that are distracting. Shoes on tile floors, heavy jewelry, and phones can create distracting noises. If possible, you can also move closer to your audience so that they can hear you more comfortably; this technique also develops trust with your audience. Here are some tips for managing volume effectively:

- Do not be afraid of being too loud, many people speak too quietly. As a rule, aim to use a slightly louder volume for public speaking than you use in conversation.

- Consider whether you might be an exception to the rule. If you know you tend to be loud, you might be better off using your normal voice or dialing back a bit.

- Think about volume in relation to content. Main points should usually be delivered with more volume and force. However, lowering your voice at crucial points can also help draw in your audience or emphasize serious content.

Pitch

Pitch refers to how high or low a speaker’s voice is. The overall pitch of people’s voices varies among individuals. We also naturally vary our pitch when speaking. For instance, our pitch gets higher when we ask a question and often when we express excitement. It often gets lower when we give a command or want to convey seriousness.

A voice that does not vary in pitch sounds monotonous, like a musician playing the same note repeatedly. Keep these tips in mind to manage pitch:

- Pitch, like volume, should vary with your content. Evaluate your voice to make sure you are not speaking at the same pitch throughout your presentation.

- It is fine to raise your pitch slightly at the end of a sentence when you ask a question. However, some speakers do this for every sentence, and as a result, they come across as tentative and unsure. Notice places where your pitch rises, and make sure the change is appropriate to the content.

- Lower your pitch when you want to convey authority. But do not overdo it. Questions should sound different from statements and commands.

- Chances are, your overall pitch falls within a typical range. However, if your voice is very high or low, consciously try to lower or raise it slightly.

Pace

Pace is the speed or rate at which you speak. Speaking too fast makes it hard for an audience to follow the presentation. The audience may become impatient.

Many less experienced speakers tend to talk faster when giving a presentation because they are nervous, want to get the presentation over with, or fear that they will run out of time. If you find yourself rushing during your rehearsals, try these strategies:

- Take a few deep breaths before you speak. Make sure to breathe during your presentation.

- Identify places where a brief, strategic pause is appropriate—for instance, when transitioning from one main point to the next. Build these pauses into your presentation.

- If you still find yourself rushing, you may need to edit your presentation content to ensure that you stay within the allotted time.

If, on the other hand, your pace seems sluggish, you will need to liven things up. A slow pace may stem from uncertainty about your content. If that is the case, additional practice should help you. It also helps to break down how much time you plan to spend on each part of the presentation and then make sure you are adhering to your plan.

In Summary

The following 16-minute video by David JP Phillips effectively pulls together the skills discussed in this chapter. According to Phillips, a communication expert, everyone can be an effective speaker. As he points out in his TED Talk, we refer to presentation skills, not talent, indicating that we all can learn to use techniques that will help us develop a relationship with our audiences and deliver high-quality presentations. Some of the skills he demonstrates in this video might be successfully incorporated in your own presentations.

(Direct link to The 110 Techniques of Communication and Public Speaking by David JP Phillips video)